Vision

By Margerethe von Trotta

I can well understand why a Catholic might approach this film with trepidation. For St Hildegard in recent years has been transformed into a patron saint of feminism, New Age and holistic medicine. Certainly from the review in the New York Times one would anticipate a straightforward feminist political treatise with vague hints of lesbianism thrown in. But really the film is not bad at all. Although obviously made from a non-Christian perspective, Vision is actually far more understanding and respectful of the religious vocation than other films in high favor with some Catholics – including those in the Vatican. I need only name in this regard the two most recent, horrendous depictions of the life of St Therese.

Obviously, Vision includes much that is usual in a contemporary and specifically German film. There is an enigmatic opening sequence, for example, where a terrified people is told by clergy to expect the immediate end of the world. The next day (nothing having happened) children emerge into the beauty of the morning. It is similar to the emergence of Audrey Hepburn from the confines of the cloister into the light of the world at the conclusion of the Nun’s Story.

St. Hildegard is presented as an oblate to a double monastery of men and women laboring under dark, “patriarchal” oppression. The male superior, devoted exclusively to monetary gain and social-climbing, is played as a dastardly villain who does everything short of twirling his black mustache. The nuns practice savage corporal chastisements presented in gruesome detail. The representatives of the church tend to be grim, fanatical , blustering types – in contrast to the wise, understanding Hildegard. The film is studded with other clichés: we hear of the “40,000 books” of the emir of Cordoba compared to the Christians’ 400.

But as the film progresses, the stereotypes seem to recede into the background while the character of Hildegard and her fellow nuns comes to the fore. This film seems to make a serious effort to depict St. Hildegard in terms of her own time and as a religious woman. She and her sisters are happy in their vocation. We get a sense of a life of calm, spirituality and beauty. St. Hildegard’s convent is made up normal women with strong and sometimes sweet personalities finding fulfillment in their monastic vocation –not the neurotic, oppressed caricatures we would expect. And St Hildegard’s discourse is primarily that of a Christian, not a New Age votary. Her main task is making known the message of the Lord – as received in her visions. And not all the clerics are negative types – St. Hildegard’s confessor and (briefly) St. Bernard of Clairvaux appear in a much brighter light.

In the film’s longest dramatic sequence, St. Hildegard has an “emotional crisis” when her favorite pupil is elected to become the abbess of another monastery. She is devastated by the loss of one who had vowed to remain with her community until her death. Although St, Hildegard’s difficulty in coping with this “particular friendship” reveals a perhaps unsaintly weakness, these scenes have the advantage of injecting a note of complexity into her character. The clash also serves to shows a deeper, darker side of the younger sister, Ricardis, who had previously been played as a Maria von Trapp type.

The film does make an effort at historical authenticity. Errors are present but not overwhelming. It is unlikely, for example, that Margrave Hartwig would travel and appear at social events clad in chain mail armor. Similarly, the archbishop of Mainz probably did not receive St. Hildegard at his chancery desk dressed in chasuble and miter and accompanied by a cleric in a dalmatic. Some things, however that appear strange are (or may be) authentic. I can imagine, for example, that there was more demonstrative embracing and kissing in those days even in Northern Europe. The rules of enclosure were certainly much more relaxed in the Middle Ages then they became in the 16thcentury. And a scene where St. Hildegard and her nuns appear in elaborate white robes with their hair flowing down is authentic (although I doubt while doing so they were singing Hildegard’s Ordo Virtutum with the participation of a male cleric).

There are many other pluses. The film moves along at a brisk pace. Overall, the acting is impressive. The photography and costumes are beautiful. The locations include several well known medieval churches and monasteries in Germany. The film quotes liberally from the works and music of St. Hildegard. And there are numerous depictions of Christian liturgies and sacraments as the film understands them. More Latin is spoken and sung in this film than even The Passion of the Christ.

To conclude, even with some significant reservations, I would recommend this film as an attempt, far more honest than most, to deal with Christian sanctity and the monastic life.

Vision is being shown at the Film Forum in Manhattan.

UPDATE:

There are a number of resources for those wishing to find out more information on St. Hildegard and the region in which she lived and worked.

This website provides information on the saint and on the locations associated with her life.

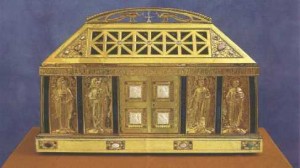

Her own monastery of St. Rupertsberg and a sister foundation, Eibingen, were later destroyed. But the parish chuch of Eibingen preserves St. Hildegard’s own relics as well as a collection of relics she acquired during her lifetime. SEE the parish website. (in German)

Her reliquary, created in 1929.

The parish church of Eibingen, finished in 1935. (Actually there are a number of churches erected in the 1930’s in Germany – and also a Russian Orthodox church in Berlin).

Finally, there is the extraordinary website of the Abbey of St. Hildegard. Thanks to the initiative of the local bishops and the generosity of Prince Karl zu Loewenstein-Wertheim-Rosenberg, the Abbey of Eibingen arose again between 1900 and 1904. The new foundation was a member of the Beuron congregation of Benedictines – the creators of a new sacred art in the second half of the 19th century. The abbey flourished and grew to include more than 100 nuns – despite setbacks such as the expulsion of the community in 1941 during the Third Reich and a period of use as a military hospital and a home for refugees.

The interior of the Abbey of St. Hildegard contains one of the most complete programs of Beuron mural painting in existence. Regrettably, much of this magnificent art was destroyed or painted over in 1967 in yet another example of a post-conciliar “restoration.” The Abbey’s splendid website thus has to resort to “virtual” images for much of its tour of the buildings and the images that adorn (or adorned ) them.

(The last three photos are from the website of the parish church of Eibingen.)

Stuart Chessman

Related Articles

No user responded in this post