St. Stephen/Our Lady of the Scapular

151 East 28th Street

It is hard to say enough about St. Stephen – next to St. Patrick, the grandest “Irish” church of the High Victorian era (1850 – 1890). Like St Patrick and Grace Church, St Stephen was designed by James Renwick, New York’s leading ecclesiastical architect of the age. The parish was founded in 1848 near East 28th Street as part of the first wave of the steady northward expansion of the Archdiocese under Archbishop Hughes – Fr. Jeremiah Cummings (described as an “American”) was the first pastor. Due to railroad construction the first church soon had to be abandoned. A new church was built 1853-54 on the present location. But that building quickly grew too small for the rapidly expanding parish. In 1865-66, the church was further expanded all the way through to 29th street. 1)

In the second half of the 19th century St Stephen’s played a central role in the life of the Catholic church of New York. From its creation it was viewed as one of the most magnificent churches of New York. The quality of the musical services matched the splendor of the surroundings. “St Stephen’s, because of its great beauty and the great merit of is choir became one of the attractions of New York City and was frequented, especially on Sunday at vespers, by so many strangers as to cause annoyance to the devout.” But the merits of this parish bore more lasting fruit. Orestes Brownson and his family were members of the congregation for many years. And then there was “the baptism on July 7 1861 of a young Persian, Alabab Shirazazazals (sic!) who renounced the Koran and received at the font the name of Andrew.” 2) By 1878 the population of the parish numbered twenty five thousand – and St Stephen’s unfolded the usual broad palette of activity typical of a Catholic parish in the 19th century. St. Stephens clergy also at first had to look after the Catholic population of nearby Bellevue hospital. 3)

The representative figure of this era was Father Edward McGlynn, who succeeded Fr. Cummings as pastor in 1866 and acquired national and even international prominence. We cannot describe in detail here all of Fr. McGlynn’s accomplishments. He was responsible for the completion of the expansion of St Stephen’s and for commissioning most of the decoration – the Brumidi paintings, the windows, the altars. He became a passionate advocate of social justice in the age of the most extreme capitalism. Unfortunately, he adopted perhaps a little too readily the economic theories of Henry George – a kind of home grown American socialist. That brought him into conflict with Archbishop Corrigan and led to his removal from St Stephen’s in 1887 and even to his excommunication. With help of the Vatican, peace was eventually made. Fr. McGlynn eventually received another pastorate in Newburgh, New York. When he died in 1900, 30,000 people filed by his coffin in his old parish of St. Stephen’s. 4) His succesor, Fr. Charls Colton, pastor until 1903, paid off his predecessor’s debts (St Stpehen’s was finally consecrated in 1894) and built the magnificent school building next to the church. This is still in operation as a Catholic school but is affiliated with Epiphany, not St. Stephen’s, parish.

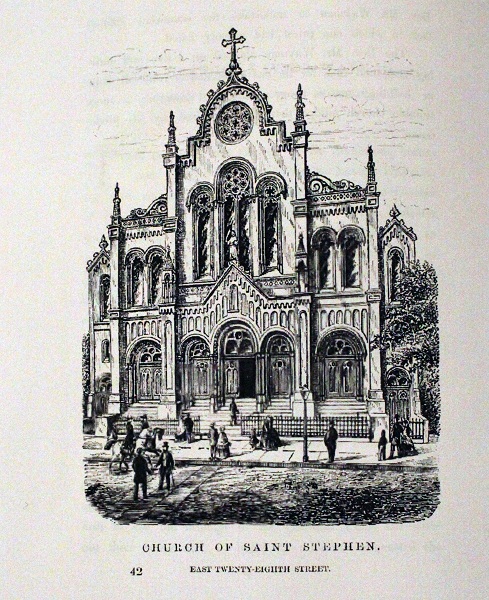

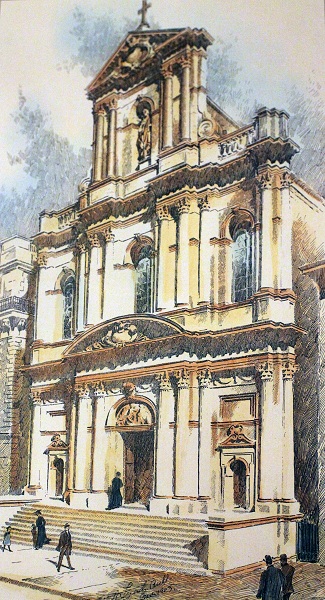

The Architecture. St Stephens presents an unprepossessing appearance to the visitor both on East 28th and 29th streets. The unique façade on 28th street, short and squat, is composed of superimposed Romanesque arches and is covered in a kind of brownstone plaster. The façade on 29th street is more drab. But this was not always so. Old images show that in Victorian times the main façade was elaborately ornamented and probably gaily painted. The present rather depressing appearance apparently dates from an unimaginative restoration in the late 1940’s. The idea, however, that the outer appearance of St Stephen’s was inadequate in comparison to the interior must have circulated at a much earlier date. A project for a magnificent neobaroque “beaux-arts” façade was published in The American Architect magazine in 1903. It was never built.

The original appearance of the facade of St. Stephen’s in Shea,”The Catholic Churches of New York City” (1878) (above) and in an early photograph (below).

The unrealized project for a new facade on East 28th Street from “The American Architect” (April 1903)

The surprise on entering the church through a narrow vestibule is all the greater. The visitor stands overwhelmed by the scale of this church – one of the largest Catholic houses of worship in the city. The nave broadens out into a generously proportioned transept and terminates in a large sanctuary – if one largely windowless. The complex, rhythmic vaulting of the ceiling – blue, studded with stars – is fascinating. With St Stephen, Renwick certainly created an interior of harmonious, spacious grandeur.

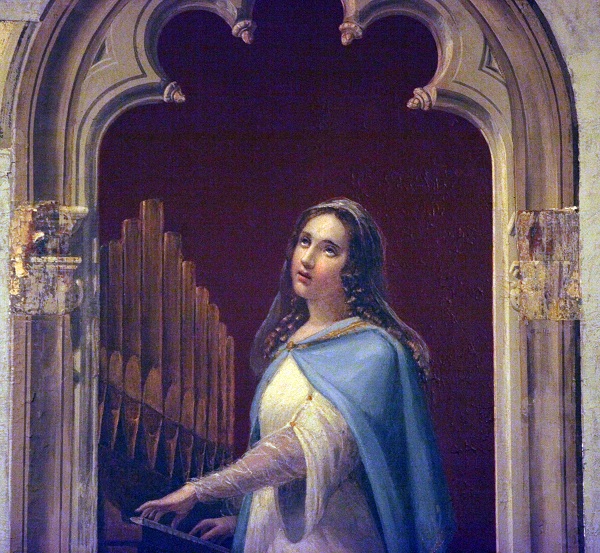

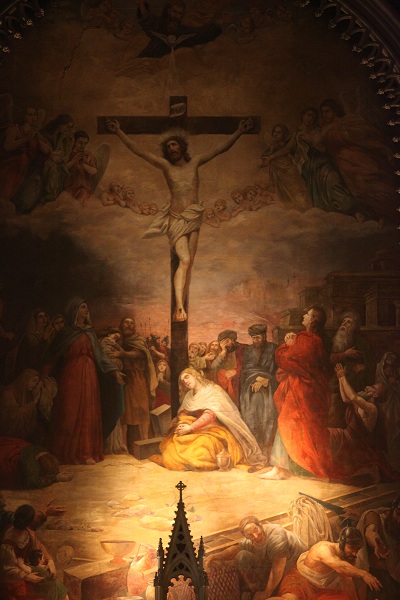

The Paintings. What is of course unique to St Stephen is the elaborate, colorful painted decoration by Constantino Brumidi, executed in the 1860’s and 1870’s.. He had started his association with St. Stephen’s with the original painting for the high altar of the pre-civil war church. In the expansion in the 1860s this image of St Stephen was moved aside and the towering crucifixion painted in the apse. There are very few windows in the sanctuary – surprisingly, a topic of theological discussion at the time – that gave Brumidi a vast space to work with. But he by no means confined his efforts to the high altar. There are frescos in the choir lofts, in the rear of the church. Naturally he could not have executed all of this himself – the parish provides a helpful guide which estimates the participation of assistants for each work. 5) Brumidi’s style is as unique as the painted cycle itself – a combination of baroque, neoclassical and renaissance.

This view of the sanctuary gives an idea of the sheer volume of the painted decoration in St. Stephen’s.

Above and below: St. Cecilia in the rear of the Church (below the organ loft).

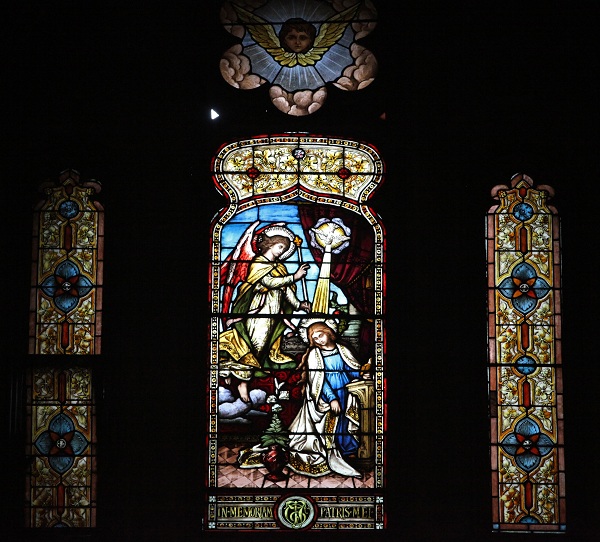

The Windows. Next to the paintings it is the stained glass that dominates the interior. St. Stephen must have the largest area of stained glass of any Catholic church in the city other than St Patrick’s cathedral. Largely by Mayer of Munich, the windows impart to the otherwise solemn interior a colorful, festive glow – as already noted by Shea in the 1870’s. 6) Almost every imaginable saint and devotion has received its commemoration in glass. The windows are by a wide variety of hands and seem to have been installed over considerable span of years. Some are sophisticated, others downright crude. Yet others seem never to have been executed – or to have been destroyed in the course of years. There is, for example, the ghost of a rose window sporting an Irish harp in one of the transepts.

The Sculpture and Altars. Statues and altars play a subordinate role in the nave and transepts of this church. As in most High Victorian era churches we have the usual heterogeneous assortment of statuary in plaster and stone assembled over many years. Some are charming, others crude or pedestrian. All seem lost in this vast space. Devotion also seems slack – few candles are burning here. And squatting in the center of the nave is an outrageous Conciliar horror of an altar. Just as in St John the Divine, the fact of declining congregations has been addressed by erecting a jerry-built altar in the middle of the church. But this travesty has produced an unanticipated benefit. For in the unused sanctuary we are delighted to encounter Victorian altars, communion rails, pulpit and statues – all in white marble, all in pristine condition. As Shea says, “the three marble altars are the finest ever seen in a Catholic church in this country.” 7) It is one of the most magnificent and best preserved sanctuaries of a Catholic church in New York! You should contemplate this superb, resplendent sanctuary before subscribing to the carping criticism so often brought today against the alleged retrograde “Irish” taste in church décor.

After the glory days of the 19th century, St Stephen’s parish seems to have fallen into a slow but steady decline as the paucity of post-1914 artifacts in this church so eloquently witnesses. It seems unclear to me why this should be so: the surrounding area, although growing more commercial, remained to a great extent rather middle-class residential. Murray Hill to the immediate north was, until the not-too-distant past, home to a fairly traditional Catholic minority. Certainly the founding of Our Saviour parish in the 1950’s did not help. And of course there is the usual Archdiocesan indifference to the artistic legacy of the past. The fabric of the church fell into deep neglect – as remains evident today.

In the 1980’s the nearby Carmelite parish of Our Lady of the Scapular was closed and St Stephen’s now became the combined parish of Our Lady of the Scapular/St Stephen’s, entrusted to Carmelite direction. Recently, for undisclosed reasons, the Carmelites were removed from the parish which thus returned to the care of the Archdiocesan clergy. In 2007, the nearby parish of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary was closed and folded into St Stephen’s as well(Sacred Hearts survives as a chapel). Several years ago the parish worked out a grand multimillion dollar renovation scheme – which would have finally succeeded in renovating – or should I say wrecking – the sanctuary which had survived intact for so many decades. Fortunately, this was halted at the direction of the Archdiocese – ominously, but only because of the pending “reconfiguration” of the Archdiocesan parishes. For, whether real or imaginary, the fear of closure has hung over St. Stephen’s for many years now.

But this risk may have a silver lining. It is curious, given the steadily increasing Traditionalist activity in the New York metropolitan area, that no Traditional order has received an invitation to Manhattan. Traditional orders flourish in the “boondocks” – Pequannock or West Orange – but not in New York itself. Now of all the old parishes of New York, St Stephen’s, with its pristine sanctuary, would be among the best suited for a establishing a Traditional parish. Who knows – if maintaining such an incomparable landmark as St. Stephens is beyond the resources of the Archdiocese, maybe the FSSP, the Canons of St John Cantius, the Institute of Christ the King or even the Oratory can lend a hand?

One afternoon, I met a young woman who had wandered into this church (any church?) for the first time and stood admiring the many works of art. She told me that had lived in the neighborhood for many years yet had no idea that all these beautiful things existed here. I have heard the same sentiment expressed several times since by visitors to St. Stephen’s. So, just as it did in the 1860’s, St. Stephen continues to impress those fortunate “strangers” who find their way inside. It is high time that the Catholics of New York also realize what a precious inheritance they possess in their old churches – and, if opened to the revival of Tradition in the liturgy, what an effective tool for evangelization they could become.

1. Shea, John Gilmary, The Catholic Churches of New York City (Lawrence G. Goulding & Co, New York 1878) at 659-660, 663-664

2. Shea, op. cit. at 662.

3. Shea op. cit, at 666, 672.

4. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_McGlynn (with many citations)

5. http://churchofststephen.com/chu_AB.htm

6. Shea, Op. cit. at 664.

7. Shea, Op. cit. at 664.

Related Articles

3 users responded in this post