Our Lady of Guadalupe “at St. Bernard.”

Our Lady of Guadalupe at St Bernard

328 West 14th Street

If the enterprising sightseer ventures over from Union Square and heads westward on West 14th Street, he gradually leaves behind the brave new world of gentrification to enter a grittier if steadily evaporating past. He strolls past several blocks of dilapidated structures occupied by discount stores, Duane Reades, union headquarters, the Salvation Army and other assorted medical, welfare and educational institutions. After crossing Eighth Avenue, the buildings appear older and more diminutive – ancient brownstones and walk-ups. Relics of prior religious life can be glimpsed here and there: until the recent past “St. Zita’s Convent” could still be barely made out on one homely building. 1) Two forlorn Roman temples, formerly proud banks but now nondescript stores, straddle the intersection with Ninth Avenue, still displaying their brass beehives, stone eagles and domes.

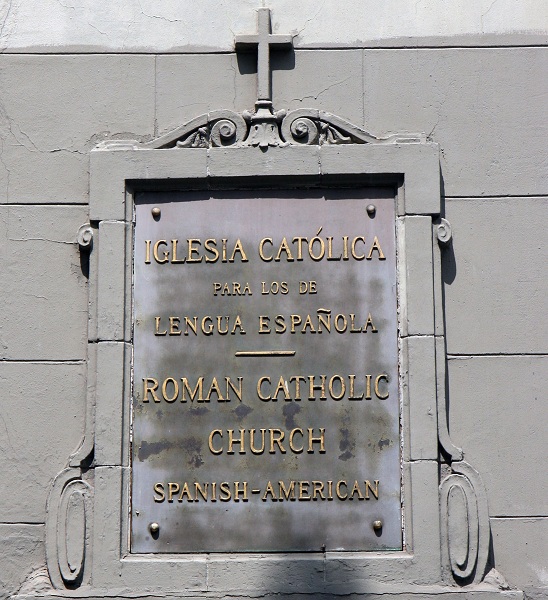

Here at 229 West 14th Street also stands the former church of Our Lady of Guadalupe set in a row of pre- Civil war townhouses. While most have been hideously mutilated a select few remain in a magnificent state of preservation. Number 324 in particular recalls the now incredible fact that in those distant pre-Civil War days this part of the street was a very upscale part of town. Indeed the old Our Lady of Guadalupe itself is one such townhouse – circa 1850 – albeit with a projecting porch or façade in the style of a Spanish colonial church. It is of grey stone with elaborate iron railings and lamps – all finely cast and carved. The surprisingly high quality of the façade – added in 1921 – is easily explained: the architect was none other than Gustave Steinback, the man responsible for Blessed Sacrament Church, one of the greatest Catholic houses of worship in the city! 2) A plaque announces in English and Spanish that this is the parish of the “Spanish –American” people.

To enter, the visitor had to walk up a steep flight of steps and step through a glass and wooden door to enter the long, narrow church, It was small – only a chapel, really. For this was simply the main suite of rooms of an old New York townhouse, converted in 1902 into a church! This house once belonged to the famous Delmonico restaurant family…

This interior was painfully modest yet dignified. The color scheme was appropriately festive: pink with gold garlands outlined in green and red. Pillars of fake yellow marble were set against the walls of the nave. More of the same pseudo-marble, but green, adorned the sanctuary. Vatican II left scars only on this part of the church – the communion rail vanished and a tiny freestanding altar was erected. The only remarkable furnishings were the magnificent, ornate metalwork: sanctuary lamps, lectern and the tabernacle in bright gilt.

The stained glass windows were few but distinctive – especially the brilliantly colored image of Our Lady appearing to Juan Diego over the entrance door. The names of the donors of the windows were Irish, German and Italian – were the windows brought from a different church? More likely the dedications reflect the origin of this church as an Archdiocesan initiative for the entire Spanish speaking population. For in 1902, a few weeks before he died, Archbishop Corrigan established Our Lady of Guadalupe as the very first church for all Spanish speaking Catholics of the city – some 15,000 even then! It was originally entrusted to an order, the Augustinian Fathers of the Assumption who remained until about 1998. In 1912 this small church was staffed by a pastor and eight other fathers of the order. 3) From this beginning, the “Hispanic” (to use the new barbarism) population grew to eventually become the dominant “nationality” of Catholic New York.

Against the rear wall of the sanctuary stood a baroque white marble reredos enshrining a large greenish copy of the miraculous image of Our Lady. For Our Lady of Guadalupe was that rarity among New York and even American churches – a genuine place of pilgrimage. Numerous (real!) candles were always lit, and there were always souls praying. And Our Lady of Guadalupe also continued to flourish, despite the progressively more out-of-the- way location, the growing crime and poverty. For there was always Our Lady to turn to.

Alas, this shrine is now a thing of the past. For, with inimitable timing, the Archdiocese closed Our Lady of Guadalupe only one year after the festive celebration of its 100th anniversary. The parish was transferred to the neighboring parish church of St. Bernard’s. After several false starts, the move of the miraculous image took place September 1, 2003. The former church of Our Lady of Guadalupe would serve as a parish center – for the time being. Right now (December 2012) the former church is covered with scaffolding – the parish office tells me it is being renovated to serve as an adult education center of the parish.

In The New York Times, Daniel J. Wakin reported on the closure of Our Lady of Guadalupe with remarkable understanding and sympathy. He described the artistic and historical merits of the church and reflected on its ethnic character. This outside observer was struck by the positive values, ranging from Marian processions to good cooking, of a national parish which to our Vatican II church represents only a “ghetto” of “cultural” or “ethnic “Catholicism. While the distraught parishioners faced with dismay the loss of their sanctuary, the archdiocesan spokesman only spoke lamely of the need to allocate material resources more effectively.

If our visitor continues his stroll a block further west on 14th Street he encounters the abovementioned parish of St Bernard’s, or, as it is known now, Our Lady of Guadalupe at St. Bernard’s. The exterior of this church – its best feature – boasts twin towers, a rose window, elaborate stonework, striking wooden doors and ornate ironwork fences and railings. (An illustration from 1878 shows spires on the towers. Were they ever actually built?) 5)

The façade, embedded in a row of brownstone walk-ups, complements and enhances the streetscape by reason of its restrained dimensions and the color of its stone. Yet this same façade, through an elaborate interplay of windows, doors, arches and stonework, unambiguously proclaims its character as a house of God. What a fitting symbol of the Church: in the midst of the world yet separate from it.

“This church edifice itself is a conspicuous monument of the piety and zeal of priest and people. Of a true ecclesiastical style, grand and imposing, it attracts the eye of thousands passing up and down the adjacent avenue and none has any occasion to inquire what the building is, for it speaks for itself, that it is a Catholic church.” 6) (emphasis added)

Shea here succinctly states the exact opposite of the architectural philosophy that has prevailed in New York and elsewhere since the Second Vatican Council.

St. Bernard’s, like Holy Innocents some 23 blocks to the north, is a prime New York representative of the Victorian Gothic edifices erected by that prolific and underestimated architect Patrick Keely. Begun in 1873 and finished in 1875, it was dedicated by Cardinal McCloskey on May 30th of that year – the first dedication of a church by an American cardinal. 7) On that occasion, the throne draped in scarlet, the magnificent decoration of the altar, and the light of the new stained glass windows shining upon the procession all “showed the ancient faith in all the grandeur of its ritual.” 8) On West 13th Street, moreover, stands the grandiose former parochial school of St. Bernard’s, erected after 1914. Even though it was closed in 2001, Notre Dame School, a Catholic girls’ high school, took over the premises.

This parish was originally Irish. From its humble beginnings in 1868, St. Bernard’s soon became one of the most important parishes in New York. Its neighborhood changed after the Civil War from upscale residential to commercial and industrial. The expanding parish undoubtedly was more middle and working class as well. Like its sister parishes in the 19th century, St. Bernard’s followed a course of expansion and the unfolding of all kinds of initiatives – meriting special mention by an early chronicler was the celebration of a Solemn High Mass each year on the feast day of St Bernard (August 20).

Like so many other churches, St. Bernard’s was abandoned by its original population in the exodus in the 1960’s. Since those times of troubles St. Bernard’s parish led a miserable existence. Even when the West Village and Chelsea started their ascent as trendy (and expensive) residential areas, St. Bernard’s found no way to connect with their new inhabitants. I admit that the residents of these neighborhoods are among those least inclined to hear the Christian message, but I doubt the old regime at St. Bernard’s parish even tried to make it known. By 2003 we hear that only “dozens” attended mass here on sunday.

Indeed, perhaps the most noteworthy feature of the pre-2003 life of this church is that it was always closed. In many attempts over the years I was never able to gain entry. As a prominent, weathered sign on the façade, proclaiming BINGO, informed us, only the basement remained regularly open during the week for old ladies. Now that old St. Bernard’s has become the new Our Lady of Guadalupe (“at St. Bernard”) one definite plus of the new regime is that you can now go inside. Indeed, a blessed feature of so many “Hispanic” churches of New York is that they are actually open – an answer to the Catholic need for a place of prayer and devotion throughout the day.

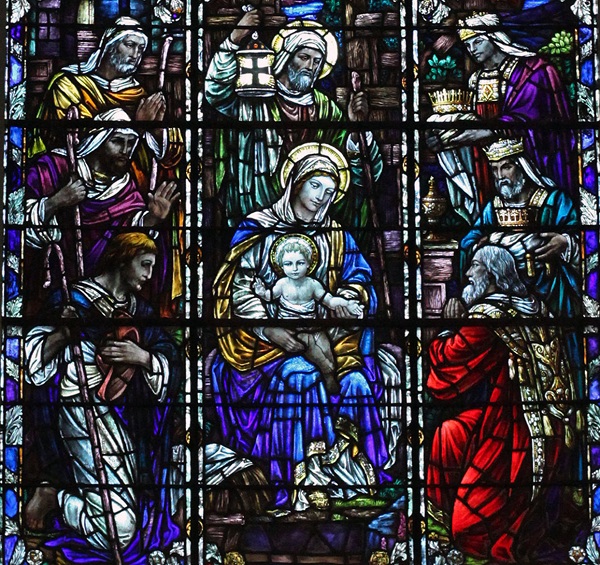

The modestly dimensioned, almost square interior, adorned with galleries like many of the more ancient New York churches, is gaily painted – in an extravagant color scheme of green and gold. It features faux marble columns reminiscent of the interior of the former church of Our Lady of Guadalupe. The architecture resembles many other parish churches designed by Keely – again, the visitor thinks of Holy Innocents in Manhattan. The stained glass windows in the nave vary greatly in quality – some at ground level are very fine but those above the gallery seem the work of a different and cruder hand.

The sanctuary, however, has the remnants of a much more sophisticated, unified décor (stained glass, paintings, mosaics, stone altars and niches for now missing statues). The explanation for these inconsistencies is a disastrous fire that gutted St. Bernard’s in 1890. Rebuilding must have proceeded in several stages over the following years. The art was that of the more sophisticated, “Golden Age” of Catholic Church architecture which extended into the 1920’s; the decoration of this sanctuary resembles the decor of St. Malachy’s church completed in 1911.

The Presentation: one of the fine paintings in the sanctuary attributed to Wilhelm Lamprecht (1838-1922), a German artist who left works in churches all over the United States.

Nowadays, the real remaining artistic glory of this church’s interior is a set of the three large stained glass windows at the rear and to the sides of the sanctuary that date from this restoration. Two are magnificent in their intricate detail and abundance of color. The third, on the right of the sanctuary, is a genuine rarity in a Catholic church: a Tiffany – but is it really his? – Easter window. The standing figure of the standing Christ of the Resurrection, bathed in dazzling white, emerges from the depths of a many-hued blue darkness.

The Tiffany window.

Over the last ten years the merger of the two parishes has occasioned significant restoration efforts but has created little of aesthetic value. The impressive doors of the façade seem to have been only recently restored. We have mentioned the exuberant new color scheme of the interior – a definite improvement over the hideous yellow paint job that disgraced the church in 2003. The furnishings of the nave, however, are limited – a nondescript statue of Juan Diego now kneels in the darkness of the nave. Even worse is a cramped “Eucharistic chapel” against the rear wall of the church – apparently the former baptistery . Worshippers sit in a few movable chairs and face an exposed host – with their backs to the sanctuary!

Our Lady of Coromoto, patroness of Venezuela.

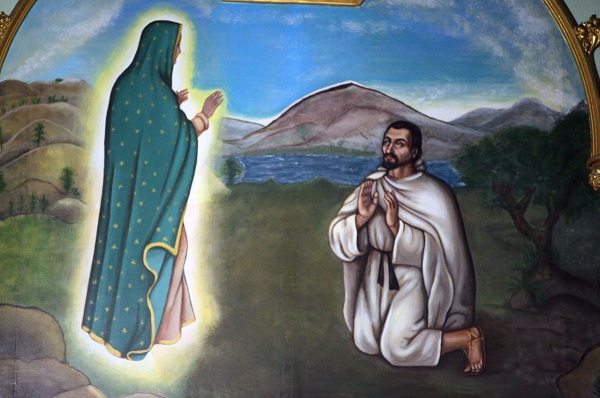

What has been done to the sanctuary, however, to implement the new dedication to Our Lady of Guadalupe borders on the shocking. A small altar squats in the bare sanctuary, level with the nave and with no communion rail. Surrounding the altar are rows of movable chairs. On the rear wall, an “artist” has painted in bad comic book style some scenes of Mexican life and of the legend of Juan Diego. In the center, directly on the wall, is the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe apparently by the same hand. To frame these paintings, a structure has been affixed to the rear sanctuary wall featuring green and gold columns, garlands and swarms of cherubs (like the angels adorning St Agnes on East 43rd street). To call it a reredos is to take liberty. To be fair, I do not know how much of the original decoration of the sanctuary had survived until the merger with Our Lady of Guadalupe – perhaps much of it had been destroyed long ago in some post-Conciliar project of “renewal.”

One of the new paintings.

Spiritually, the results of the merger also seem to me to be mixed – although, given the natural piety of the Mexican people, this parish appears to have a more active spiritual life than many others on this island. In contrast to the lively devotions always being rendered the old church, however, I have encountered relatively few worshippers now in repeated visits on weekdays – maybe a dozen souls this past Monday afternoon. Instead of the former real votive candles, only a few small banks of electric candles stand here and there, not many of them lit. Moreover, a large Mexican national parish – which St. Bernard’s has become – may be out of place in this area of the city. Perhaps devotion will pick up. As for now, though, silence and darkness seems to have replaced the busy activity of the former shrine. It is indeed far easier to destroy a shrine than to create a new one!

The original St.Bernard’s, a mediocre post-conciliar parish, imbued with a secular mentality that understood its mission only to be a “service provider” of masses and bingo to an inherited congregation, manifestly failed the test of evangelizing this Babylon of the 21st century. Yet just a block to the east, a tiny national parish that remained faithful to a truly traditional paradigm of pilgrimage, reverence and contemplation – combined with a dash of modest yet real beauty – triumphantly withstood the challenges of this age. Naturally, it is this, the successful church, which then had to close!

All too often measures of “economic necessity,” like the closure of Our Lady of Guadalupe, only disguise – temporarily – monstrous failings in leadership, liturgy, mission and above all faith. These are the real afflictions of the Church that remain unaddressed while attention is focused on local, provincial constraints of money, congregation size and personnel. Ten years ago, in this remote corner of the city, a small tragedy played itself out. A tiny parish that had survived and flourished through so many years of privation at last succumbed to the crisis in the Archdiocese and the Church. A crisis that has continued to grow since then and now threatens to engulf many other parishes in the next few months and years.

1) The Mormons acquired it in 2002 after its home-grown New York order, The Sisters of the Reparation, had to end operations after over a century of charitable sacrifice). See

http://www.nytimes.com/2005/09/04/nyregion/thecity/04fyi.html?_r=0 ; http://www.patheos.com/blogs/mcnamarasblog/2011/09/sisters-of-st-zita-1903.html ;

http://thevillager.com/villager_44/mormonsmoveinto.html

2) 3) The Catholic Church in the United States of America: Volume 1 (New York City: The Catholic Editing Company, 1912), at 32; The Catholic Church in the United States of America: Volume 3 (New York City: The Catholic Editing Company, 1914), at 357.

4) Daniel J. Wakin, The New York Times, “For the Church’s Latino Faithful, a New Home, “ 4/17/03; “A Call to Worship Becomes a Call to Eat,” 4/22/03.

5) Shea, John Gilmary, The Catholic Churches of New York City (Lawrence G. Goulding & Co, New York 1878) at 204.

6) Shea, John Gilmary, The Catholic Churches of New York City (Lawrence G. Goulding & Co, New York 1878) at 209.

7)http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Our_Lady_of_Guadalupe_at_St._Bernard’s_Church_(New_York_City)

8) Shea, John Gilmary, The Catholic Churches of New York City (Lawrence G. Goulding & Co, New York 1878) at 208.

Related Articles

2 users responded in this post