The Church of St Brigid and St. Emeric

123 Avenue B and East Seventh Street

This January a ceremony took place that was startling and audacious even by the standards of the New York Archdiocese. Cardinals Dolan and Egan celebrated the reopening of the venerable church of St Brigid – a sanctuary once earmarked for the wrecking ball. Now the bizarre element was that the preservation and resurrection of St Brigid’s had been achieved only by an acrimonious multiyear battle with the Archdiocese – led by Cardinal Egan himself! It was reported that the leaders of that struggle played a decidedly minor role in this ceremony commemorating the restoration of the parish.

Nevertheless it was an auspicious event – the first time a historic church had been rescued after a determination by the Archdiocese that it must go. You see, a mysterious donor had stepped in with the $20 million the archdiocese estimated was needed for repairs. The energetic parish team had made a powerful case for St Brigid’s – highlighting especially this parish’s historic links with the fate of the Irish immigrants in New York. We heard much concerning the great famine of the 1840’s; the participation of Irish shipwrights in the construction of this church; and the special significance of the carved heads and vaulting of the interior. Later, there was the saga of the descent of the neighborhood into poverty – and the determined struggle of the parishioners over the decades to keep parish and school alive.

We must admit though, that the early chroniclers of St Brigid’s did not see this church as playing such a central role in the life of Irish 19th century New York as this narrative would have it. Nor do they mention any particularly strong association with the Famine – at least no stronger than that of many other churches in the Archdiocese. What interested them seemed to be not St. Brigid’s historical significance but the architectural statement made by its building. Until the construction of St Brigid’s (or Bridget’s, as it seems to have been known in Mr. John Gilmary Shea’s day – 1878) starting in 1848, Catholics had either acquired former Protestant churches or had erected neoclassical temples like St. Peter’s. That was a style increasingly felt to be non-Catholic. St Brigid’s, on the other hand, was the first purpose-built Catholic Church in a proper Gothic style (ignoring, of course, Old St. Patrick’s). And the architect was the soon-to-be-ubiquitous Patrick Keely of Brooklyn, who went on to build innumerable Catholic churches across America. (Holy Innocents and St Bernard’s are New York City examples).

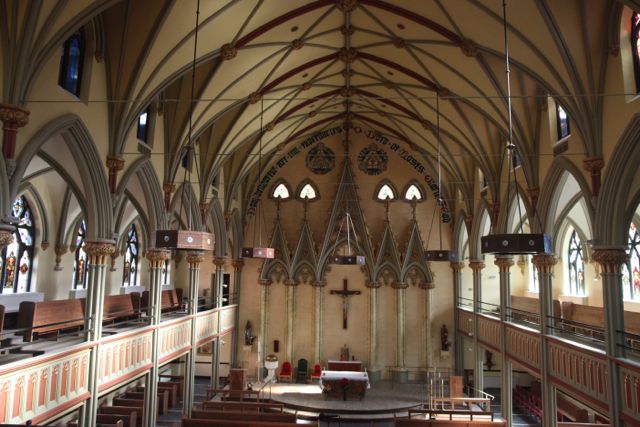

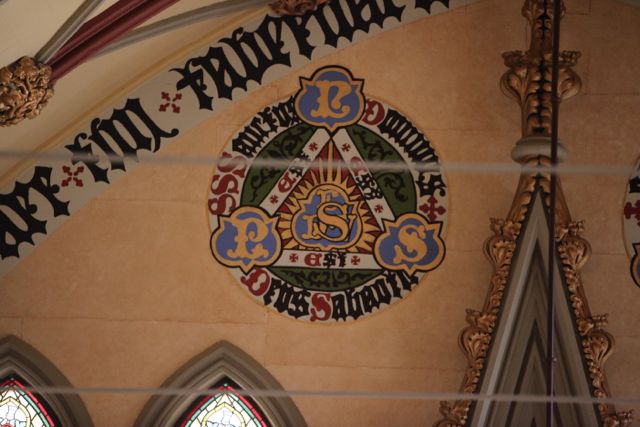

This enthusiasm seems a little strange to the observer. For what strikes us today is how similar to Protestant churches of that day is the plain, almost boxlike interior, of St. Brigid’s, with its galleries and narrow sanctuary set against a flat wall. But it is an airy, light filled space. And attached to the wall of the sanctuary is a very early ”reredos” of partially gilt Gothic tracery. Above this, on the wall, are ornate (original?) painted emblems and lettering.

A communion rail in front of a lectern?

But this “Protestant” impression derives to a great extent not from the original architecture but from post conciliar “renovations” and then a wholesale gutting by the contractors of the Archdiocese in 2006 when it seemed this St. Brigid’s was doomed. Except for a few panes, for example, almost all the stained glass – added in the second half of the 19th century – was lost at that time. As a visitor recorded in an account published in 2001:

“Note the original Bavarian stained glass and fourteen oil paintings of the Stations of the Cross by L. Chovet of Paris….Look up to the music loft to see organ pipes encased in carved wood topped by Gothic spires and angels.”

All this has been swept away. 1)

The recently completed restoration has given the interior a very pleasant color scheme and has inserted some stained glass taken, so we are told, from St Thomas the Apostle in Harlem – a tragically wrecked masterpiece used as a quarry for a number of churches. But the minimalistic, modern, sanctuary once again reinforces the “Protestant” ambiance.

The exterior is also plain but satisfying. For the restored church presides splendidly over the mostly lower structures surrounding Tompkins Square. It is one of those fortunately not infrequent examples in New York of a Catholic church serving as the architectural anchor of an entire streetscape (like Our Lady of Loreto, St. James or St Bernard’s). When St. Brigid’s facade still was topped by steeples this dominance was even clearer – these had been taken down years ago for “Structural reasons” and were not restored. Helped by St. Brigid’s, Tompkins Square nowadays has a weirdly European or English appearance about it. And the new low-rise luxury buildings on the side streets leading off the park seem almost surrealistic to anyone familiar with the area several decades ago… Strangely, amid all the vicissitudes of this parish, the parochial school of St. Brigid’s, founded in 1856, is still in existence.

The former school of St. Emeric is on the far left.

Where there is life in this vale of tears, there is also death. If St Brigid’s has returned from the edge of the grave, the nearby parish of St Emeric’s has in turn succumbed. This parish was a recent (1950) creation of Archbishop Spellman. The “moderne” church and school of St Emeric resemble much more a suburban parish of that era than a typical house of worship in one of the oldest neighborhoods of New York. St. Emeric’s was the successor to the ancient parish of St Mary Magdalene, which had been razed in the 1945-6 to make way for the vast development of Stuyvesant Town. The unusual patron – Emeric (Imre), a Hungarian royal saint of the 11th century – reflects Cardinal Spellman’s admiration for the resistance of the Hungarian people to communism. (There already was a church in Manhattan dedicated to St. Emeric’s father, St. Stephen of Hungary) The congregation of St. Emeric was split between the middle class residents of Stuyvesant Town to the north and the poorer inhabitants further south. 2)

Now the parish and its school are closed or dedicated to other purposes. St. Emeric’s is merged with St Brigid’s – now the parish of “St. Brigid and St Emeric.” The former church remains surrounded by junk and the refuse of Sandy. And it is set against the backdrop of the most distressing neighborhood of any Catholic church in Manhattan: a gigantic power plant. Truly it seems like the Church has expired here – at what seems like the end of the world! Yet a short walk away the much more ancient parish of St. Brigid’s has defied the odds and remains very much alive. Death and rebirth are the facts of the world; but what has taken place here on the Lower East Side should give every Traditionalist some fleeting comfort amidst the “encircling gloom.”

St. Emeric’s church (left) and the power plant...

A sorrowful end for this church. It featured an interesting reredos.

1)Cook, Terri, Sacred Havens: A Guide to Manhattan’s Spiritual Places at 54 (Crossroad Publishing Company, New York, 2001)

2) Thanks to Manuel Albino for the information.

Related Articles

1 user responded in this post