The Basilica of St. Patrick’s Old Cathedral

Mott Street (at Prince Street between Mulberry and Mott Streets)

I. The current official title for St. Patrick’s is a long one. It’s appropriate, though, for the second oldest Catholic church in New York City and the Archdiocese’s original cathedral. It is an eloquent reminder of the challenges and stresses of the establishment of Catholicism in New York. A time that this generation, living through a new era of crisis and chaos fro the Church and the Archdiocese, may be uniquely qualified to appreciate.

The raising of New York to an episcopal see in 1808 and the growing number of Catholics meant that the single Catholic church in New York – St. Peter’s – had become grossly inadequate. At a plot of land for a cemetery owned by St Peter’s church the new Cathedral was begun in 1809. Considering the one-sidedly Irish focus of the Archdiocese in subsequent generations, it is interesting to note that Anthony Kohlmann SJ, a German, founded its first cathedral! Construction was only finished in 1815. The dedication on May 4 was an extraordinary event-the new Cathedral was the largest church in New York. In attendance was a throng of 4,000 persons (“consisting of the best families of New York”) the current mayor and former mayors – including the famous De Witt Clinton. (To give some context to this festive event, the Battle of Waterloo was fought the following month on June 18). The new cathedral was still remote from the city – not too long after the dedication a fox was caught in the churchyard….

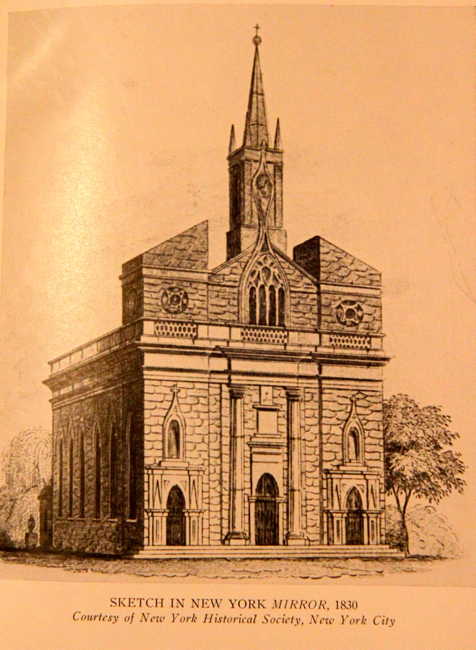

The structure itself was unique. The architect, Joseph Mangin, the architect of the New York City Hall, had employed a kind of “neoclassical gothic” idiom decades before Pugin and Upjohn. The impression it made on contemporaries in what was still “little old New York” was extraordinary: they praised the new church’s “elegance,” “ grandeur,” “ beauty” and “ magnificence.” According to the bishop of Montreal, visiting New York in September 1815: “The interior is magnificent… all the more imposing that a painter has figured on the plain wall ending the church behind the altar a continuation of (the church’s) arches and columns which seem to vanish in the distance and create such a illusion on stranger ignorant of the fact , as to persuade him that the altar is placed at only half the length of the church, although it is really is at the very end. The wonderful effect produced by this perspective makes the church pass for the finest in the Untied States.” 1). John Gilmary Shea, ever sensitive to such matters, pointed out that: “The erection of so noble an edifice had a most beneficial effect. Catholics were raised in public esteem. A community that could conceive and carry out such projects was one entitled to respect.”2)

In many respects this cathedral parish was innovative. Some of the earliest “parochial” schools were founded here (at the time religious schools were still partially funded by the state). In 1817 there was the first mission (an orphanage) in New York of three members of the Sisters of Charity, founded by Mother Seton. In 1825, a brilliant concert took place in the cathedral. The Garcia troupe had brought the first ever season of Italian opera to the United States. The singers of this company volunteered their services for a benefit concert. One of the performers was the soon-to-be world-famous Maria Malibran, The concert was a great success; with these funds and other donations the splendid brick building on Prince Street was erected for the orphanage. 3) Once again we note, even at this early period, the presence throughout the great age of the Archdiocese of a broader vision among New York Catholics than that prevailing in 1960 or 2013 – the unfolding of multifarious, sometimes highly sophisticated initiatives in architecture, music, education and care for the poor – not contradicting but mutually reinforcing each other.

While on the subject of music we should mention that in 1838 a requiem mass was celebrated here for Lorenzo Da Ponte, Mozart’s most famous librettist. Da Ponte, was not, however, buried in the cathedral churchyard, but in an unmarked grave in the new 11th Street Catholic cemetery that had largely supplanted it after 1833. (Later, after 1909, the graves there were moved to Calvary Cemetery and the church of Mary Help of Christians (demolished this year) built on the site.)

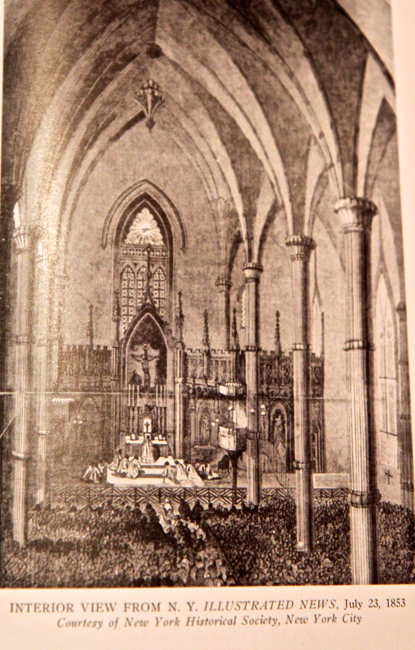

(Above) The original facade; the cathedral does not yet have the Mulberry street extension. (below) the cathedral in 1853 – the vertical scale somewhat exaggerated by the artist. (Both from Carthy, Old St. Patrick’s – New York’s First Cathedral.

This original interior did not last long, for the cathedral would shortly be enlarged. An expansion was completed in 1842 extending the church to Mulberry Street and a new sanctuary was created. The interior was dramatically lightened and redecorated. At the same time, St. Patrick’s was expanding in other directions. The cemetery was expanded by stages to Prince Street. An orphanage (later a school) was built on Prince Street. An episcopal residence and later a chancery building were acquired or built on Mulberry street. Most impressive of all, a dramatic wall with iron gates was built enclosing the cemetery, Thus, there arose over the years what is today the most impressive aspect of the old Cathedral – that is is not just an isolated church building but a whole Catholic complex, unique in the city!

That wall was not merely decorative. In its early years, prior to Archbishop Hughes, internal and external enemies beset the diocese on all sides. I will not review here the conflicts among the clergy, the battles with trustees, or the financial woes – many of which involved St. Patrick’s.

More dramatic was the confrontation with the growing anti–Catholic sentiment, which climaxed in 1836 with a march of a threatening mob against St Patrick’s and its cemetery. But they found the church and its newly completed cemetery wall defended by a large number of armed and determined men. The surrounding houses also were filled with defenders armed with muskets and cobblestones. In the face of this show of force, the mob dispersed without a shot being fired. The victory was so complete that subsequent flare-ups of anti-Catholic agitation, such as in 1844-45, largely bypassed New York. 3)

Yet the church of St Patrick’s itself retains little evidence of these early years. For the cathedral burned down to its external walls in 1866. It was then rebuilt – the facades in a much simplified style – along the lines of the many Catholic parishes coming into existence at this time. Finally, the present St Patrick’s cathedral was finished in 1879 and Old St. Patrick’s became just another parish church. In the course of time the original population moved out and St Patrick’s became virtually an Italian ethnic parish, situated at the northern end of “Little Italy.” By the 1980’s, the neighborhood of St Patrick’s had changed once again – it had become a quasi-deserted, out-of-the way corner of the city. The surrounding streets primarily featured garages, deserted storefronts or “social clubs’” associated in the public mind with a certain Italian-American organization. Like so many other New York parishes, the majority of St. Patrick’s congregation was now “Hispanic.”

The facade on Mott Street today

And today things have changed once again. Gentrification accelerated in the 1990’s and this vicinity acquired its own name (at least in the minds of real estate agents) “Nolita.” New buildings sprang up for the first time in decades, boutiques and expensive restaurants moved next door to St Patrick’s and stalls of jewelry vendors set up for business against the cemetery wall. The effect of the new trendiness on the poor, existing Catholic population of the parish was traumatic. St. Patrick’s school closed – it had existed in one way of another for more than 150 years. On the other hand, the parish today seems to be in the hands of a much more focused, dynamic and missionary leadership than was the case in prior decades. Symbolic of this was obtaining in 2010 basilica status for the old cathedral. Restoration work has been carried out on the cemetery wall. At the end of this year a renovation of the interior of the cathedral and the sanctuary, in the works since 2010, is finally supposed to commence next year. As far as the sanctuary is concerned, it will repair at least some of damage done in the post-conciliar era. Then there is the attempt of the parish to revitalize the use of the cemetery by selling spaces in a “columbarium. ”4)

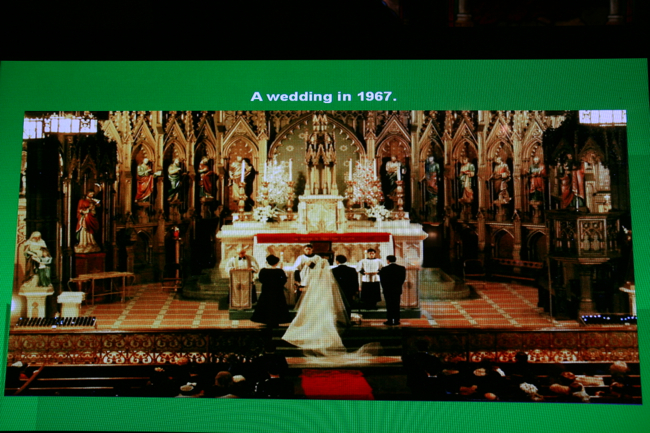

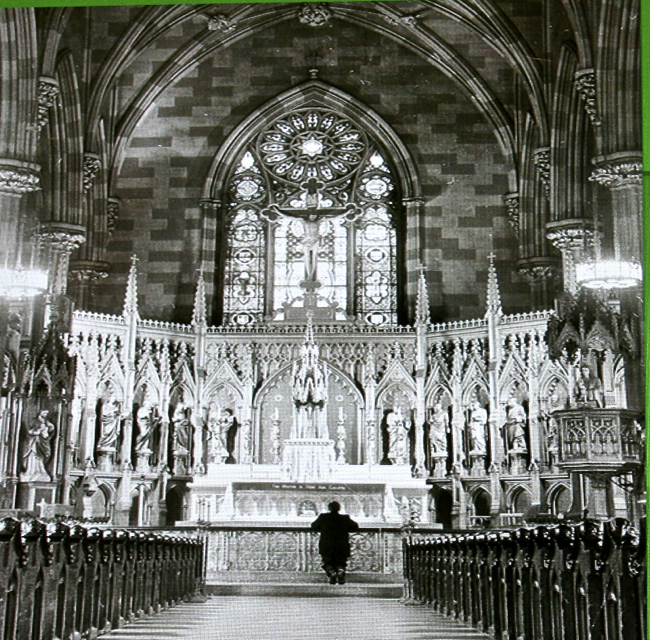

(above and below) The sanctuary before its post-conciiar “renovation.” The current restoration will attempt to recapture part of this. (From a presentation in Old St. Patrick’s on the restoration project)

II. The visitor may appreciate the “nice” bustling atmosphere of today’s “Nolita” compared to the sometimes-threatening isolation and stillness of prior decades. Yet progress comes at a price: the streets around Old St. Patrick’s are now often inundated with traffic. Still it is a unique and impressive sight: the church, the wall, the old chancery building by Renwick from 1859, the orphanage/school of 1825, the rectory, formerly the ”bishop’s house,” on Mulberry street. Where else can you get such a sense of the history of Catholicity in this city?

(Above) a gate in the cemetery wall: (below) the wall on Mulberry Street.

(above) The door to the “bishop’s house” (now the rectory); (below) the old chancery from 1859 (now St. Michael’s Russian Catholic Chapel)

And then there is the mysterious, calm cemetery – one of only handful of such oases remaining in Manhattan. The weather beaten stones witness to an era almost unimaginably remote (at least to us Americans) – burials in the graveyard proper largely ceased in 1833 (they continued in the crypt). In the repair work for the wall the gravestone of a little girl was found. From the first decade of the 19th century it had lain embedded in the wall for over 170 years…. Many are the distinguished Catholics of the past who were buried either in the churchyard or the crypt. It was an unforgettable experience in prior years to process by candlelight through this churchyard at midnight to St Michael’s Catholic chapel, located in the old chancery building, for Easter services.

St. Patrick’s itself appears distant and austere – its brownstone façade on Mott Street downright plain and even ungainly, with niches for statues that apparently were never completed. It is hard to recapture the enthusiasm of 1815 or 1819. We must remember, however, that the exterior was drastically simplified in the post-1866 reconstruction. The Mulberry street façade today is perhaps more satisfying. St. Patrick’s can be accessed from both streets.

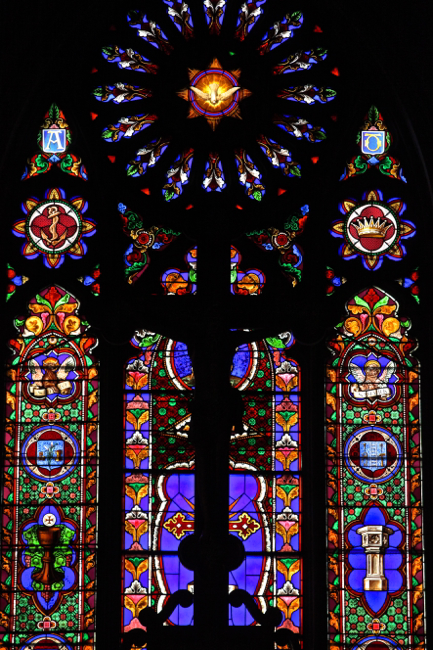

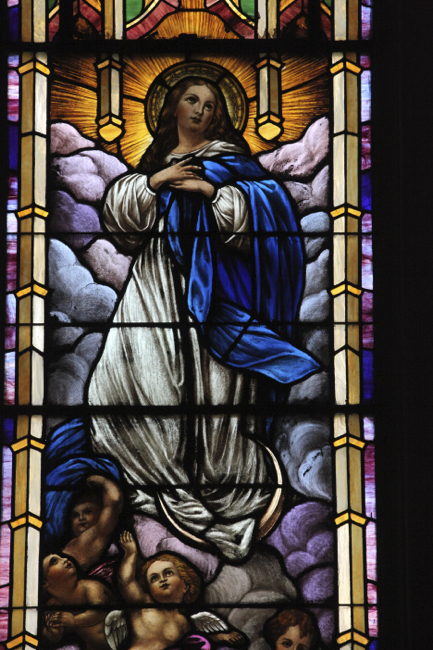

Inside, St. Patrick’s presents a dark, somber appearance. One thinks of a gothic church in Europe rather than the gaily decorated and painted Victorian churches of 19th century New York. Is this original or is it the result of subsequent repainting? Perhaps the restoration will tell us. The statuary and stained glass are also subdued. Probably here the limited financial resources of the post-cathedral existence of St Patrick’s were decisive. Aside from some very early panels – such as in the apse – which seem to date from the time it was a cathedral, most of the windows would seem to have been added much later. Although nice, they are not of the absolutely first rank.

(above) The magnificent Henry Erben organ; (below) the apse window – apparently the original window put in place after the 1866 fire and described by Shea(1878)

The two windows above are the work of (two?) relatively crude artists, whose products can be found in several other ancient New York churches. (below) A much more recent window with an Italian donor.

The sanctuary has indeed suffered in the post-conciliar era. But a splendid reredos, which appears to date from the post-1866 reconstruction, still survives. It features fine statues of the apostles (as recently as the 1960’s they were painted). It also seems to have always allowed for a freestanding altar appropriate for a cathedral. It will be interesting to see what changes the restoration will make. By the way, the baptism scene in The Godfather (one of several films shot in and around the former cathedral) was filmed at the baptismal font here. But by the early 1970’s the baptismal font had been relocated to the sanctuary – that would not have been the case in the 1940’s, the setting of the movie.

(Above and below) The reredos

The tabernacle in the form of the original facade of the cathedral.

Both a unique monument to the past and an example of an apparently recovering parish of the present, Old St Patrick’s is a perfect introduction to the history of the Archdiocese: its founding, its vicissitudes, its transformations and its present crisis. Despite being one of the “downtown parishes” now in official disfavor, we would hope and pray that St Patrick’s, now approaching its 200th anniversary, will surmount the latest challenge facing every New York parish.

1) Carthy, Mother Mary Peter, Old St. Patrick’s – New York’s First Cathedral at 23-24 (The United States Catholic Historical Society (monograph series XXIII), New York, 1947)

2) Shea, John Gilmary, The Catholic Churches of New York at 89 (Lawrence G. Goulding & Co., New York, 1878)

3) Carthy, Op.Cit at 49-50. A curious result of this concert was a dispute with the cathedral choir, who apparently felt slighted. Contemporary visitors praised the organ music and the choir (composed of both male and female singers). Carthy sourly notes (in 1947): “The use of mixed voices of men and women in church choirs was not then considered the liturgical impropriety it is today.” Id.

4) Shea, Op. Cit at 93-94.

5) We might also add to the list of these present –day initiatives the creation of a very full and informative website: http://oldcathedral.org

Related Articles

No user responded in this post