Church of Saint Jean Baptiste

184 East 76th Street and Lexington Avenue

“Ethnic parishes” are in bad repute with the Archdiocese nowadays. The creation in earlier times of separate churches for the Italians, the Slavic peoples, the Germans etc. is held responsible for the alleged surplus of Catholic churches in New York today. So the court historian of the Archdiocese, Fr. Shelley; so the publicists of the current Archdiocesan “realignment” initiative ”Making all Things New.” The party line is that since the “ethnics” have either vanished or have been assimilated we do not need their churches.

The truth is quite a bit more complicated than that. Since in the 19th century and well beyond the majority of the parishioners of the non-ethnic parishes of New York City were Irish, it could be maintained that all New York Catholic churches were “ethnic” from their origin. Yet even if we restrict the label “ethnic” only to parishes having a congregation employing a language other than English, the boundaries have been very fluid. Some churches have always been “ethnic” but with a succession of different nationalities, e.g. Our Lady of Sorrows (first German, then Italian, now ”Hispanic”). Other parishes have started out “non-ethnic” and have become “ethnic” (non-Hispanic): St. Raphael (now Croatian); Transfiguration (first Italian, then Chinese); All Saints (black – considered from the beginning “ethnic”). And, of course, in recent decades most Manhattan parishes other than the commuter churches and those located on the East Side north of 14th Street and south of 96th Street have become de facto “Hispanic” ethnic parishes. Yet others have started out ethnic and have become “generic” Catholic – e.g., St. Francis and St. John near Penn Station (originally German); St Elizabeth of Hungary (Slovak); Our Lady of Peace (Italian). Of this very last category the most spectacular example is the church of St Jean Baptiste on the Upper East Side (in earlier days, old Yorkville) 1)

St. Jean Baptiste parish was born in 1882 to serve the needs of the French Canadians. They had been present in New York from the early days of Catholicism. But in contrast to their prominence in the New England mill towns, French Canadians remained one of the smaller Catholic minorities in New York City. From its very beginning their parish accommodated other nationalities. An early focus of veneration was, just as in Quebec, St. Ann. A relic on the way to St Anne de Beaupre was venerated by a great multitude in the very first year of this parish’s existence even before its first church was finished; later in the 1880’s the parish acquired its own relic of St. Ann and the devotions continued and grew (if in competition with devotions at St Ann’s parish downtown). St. Jean remained a parish of the French Canadians until 1957. 2)

Now two circumstances radically transformed the life of the parish and created one of the most grandiose churches in New York City. First, in 1900, after early years under various pastors, the parish was placed in the care of the Congregation of the Blessed Sacrament, a religious congregation coming from Montreal. St. Peter Julian Eymard founded the Blessed Sacrament Fathers in Paris in 1856 –their first residence was in the strangely named Rue d’Enfer. (The name of the street is actually thought to have nothing to do with the underworld). Eymard labored to promote Eucharistic worship. That included preparing children for first Holy Communion, reaching out to non-practicing Catholics through the Eucharist and encouraging both Eucharistic adoration and frequent Holy Communion. 2) Of the community of Blessed Sacrament Fathers newly established at St Jean’s, Father Arthur Letellier was a particularly outstanding personality: a man of great devotion and an inspiring and visionary leader. He became pastor in 1903.

Second, the parish attracted the attention of Thomas Fortune Ryan, (1851-1928) an investor in many businesses who was reckoned the 10th wealthiest man in the United States when he died. He and his wife Ida Barry Ryan were major benefactors of the Catholic Church allover the country but especially in the South. 4) He had already established close contact with the Blessed Sacrament Fathers both at his country estate and in the city. He would attend the services at the small and new parish of St Jean Baptiste – although his residence at the time appears to have been – appropriately enough – in the parish of St. Ann. One day after having had to stand in an overcrowded service, Ryan asked Father Letellier how much it would cost to build a new church. “At least $300,000” said Letellier (a monstrous sum for the time). Ryan replied: “Very well – have your plans made and I will pay for the church.” The new St. Jean’s was born. 5)

1900-20 was a propitious time for such undertakings in New York. Previously unheard–of financial resources became available for the construction of Catholic institutions – often at the direction of wealthy patrons like Thomas Ryan. Parish priests and religious orders strove both to build impressive houses of God and also to set off their churches stylistically from their predecessors and neighbors. It was at this time that St. Vincent Ferrer and Blessed Sacrament churches were built. St. Jean Baptiste would be their rival – but not in the Gothic Idiom. Rather, St. Jean’s would be New York’s grandest representative of the Neo-Baroque.

The architect of St. Jean’s was Nicholas Serracino. He often worked for the Catholic Church particularly in the period 1910-20, employing a Neo-Baroque style. In the city his work was predominantly for national parishes – Italian and French, Time has been unkind to his legacy in Manhattan. His church of St Clare (Italian) found itself in the path of the Lincoln tunnel and was demolished in the 1930’s; Mary Help of Christians (likewise Italian) succumbed to Archdiocesan real estate dealings and was razed in 2013. But St. Jean’s, his grandest creation, far exceeding these other churches in size and magnificence, remains. It was begun in 1912 and had opened already in 1913. However, the decoration of the vast space – the windows, the altars – continued into the 1920’s and beyond.

The gray stone bulk of St. Jean’s makes a dramatic impression on its Lexington Avenue – what with its columns and pediment, intricate twin towers and dome. The façade is richly ornamented and crowned by various groups of angels.

One enters the interior through a spacious narthex. Coming into the nave, the visitor is overwhelmed by the elaborate color scheme – restored in recent renovations. The grandly dimensioned church is fully articulated with nave, aisles, transept sanctuary and dome – no “ordinary” New York parish here! The visitor’s eyes can rest on innumerable architectural details. It is one of the great triumphs of the Beaux-arts school in New York!

Most impressive of all is the colossal altar crowned by a monstrance the visual center of the church. There could be no better expression of the Eucharistic centeredness of the original founders.

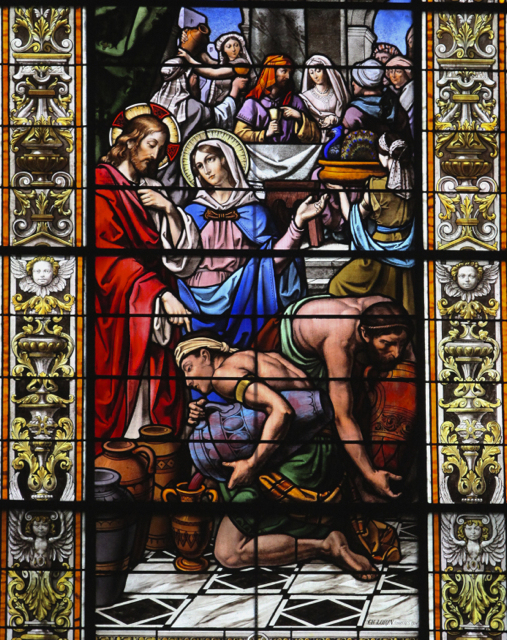

The other furnishings and stained glass reinforce the Eucharistic theme. In the sanctuary are a series of windows dealing with Old Testament types of the Eucharist. And the main windows reinforce this teaching by commemorating New Testament and Eucharistic events of more recent vintage (such the lowering of the age of first Holy Communion). This is also typical of that Golden age of New York church building – every aspect of the architecture, furnishings and decoration is intended to be in harmony, to relate and reinforce one unified message – of Eucharistic Adoration.

Miracles at the procession of the monstrance at Lourdes.

Pope Pius X lowered the age for receiving first communion.

The windows, like certain stained glass in St. Patrick’s cathedral, comes from the French studio of Lorin – in contrast to the glass from Munich or Innsbruck typically found in New York churches of that period. Certain items, like the baptismal font or the statue of St. Ann, even come from the original church.

But one unique element of St. Jean’s “furnishings” requires special mention. 19th century accounts of New York churches often mention magnificent vestments especially at major liturgical events. This is entirely in accord with medieval practice; early descriptions of churches often focus more on the precious vestments and liturgical vessels than on the architecture. Now St. Jean’s possesses two truly spectacular sets of vestments: one, the “Angelic Vestments”, medieval in style, was made in Lyon in 1900. The second, made in Belgium from 1925, commemorates the declaration of Peter Eymard as a Blessed of the Church. Recently both sets have been seen to great advantage in two traditional pontifical masses celebrated at St. Jean’s. Moreover, St. Jean’s possesses precious chalices, monstrances and ciboria as well as a bust of St. Eymard by August Rodin. 6)

Above: At the altar the clergy are wearing the 1925 Vestments; in the foreground one of the “Angelic Vestments.” Below: one of the “Angelic Vestments.”

Above and Below: the 1925 Vestments from Belgium.

St Jean’s remained a center of devotion to the Eucharist and to St. Ann for many years. The parish opened schools – the high school still exists, the grade school was closed in 1989. And, if anything, the economic level of the neighborhood steadily rose over the years. Yet in the 1960’s and after “St. Jean’s” shared the woes of New York City and of the post-conciliar Church. The liturgical changes wrought in the wake of the Council most directly clashed with the truly “Tridentine” Eucharistic orientation of the whole church. The “people’s altar “ (brought from the former lower church) stands in shocking contrast to the old high altar and its great reredos.

By 1987 the exterior was falling apart. In that year the pastor began a series of costly restorations that have continued to the present day. The structure of the church was restored and the interior repainted. Many other individual changes were made to the chapels and furnishings. This all has come at a price. As noted, the parochial school closed. Buildings of the large complex surrounding the church were sold off. The former lower church was converted into a community center and a theater.

At present the towers are being repaired in the latest campaign of restoration. St Jean’s soldiers on – among other things, the parish has a music program unusually active for a Catholic church. But do the spiritual and intellectual sources of this great structure – Eucharistic devotion and reverence for the Western classical architectural tradition – still have any relevance for the Catholic faithful in 2014? Those of a younger generation seeking to reconnect with its own religious and artistic heritage will have to give the final answer to that question. 7)

1) Should I point out that the name of this church is pronounced St.GENE’s? Certain parishioners of today either don’t know that or avoid it out of embarrassment.

2) Kamas, Rev. John A. and Lopez, Barbara O’Dwyer; Eglise Saint Jean Baptiste at 3-5 (The Church of St Jean Baptiste, New York 2001)

3) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St._Jean_Baptiste_Catholic_Church

4) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Fortune_Ryan

5) Kamas and Lopez, op.cit at 11-12. (The actual cost turned out to be a multiple of this figure.)

6) Kamas and Lopez, op.cit at 113-125.

7) In recent years St. Jean’s has seen magnificent, well attended pontifical masses in the Extraordinary Form as well as musically splendid services in the Ordinary Form.

Above: A remnant of the communion rail. Below: another view of the dome.

Related Articles

1 user responded in this post