Our Lady of Pompeii

28 Carmine Street

If you wander south on Sixth Avenue in the Village you’ll find at the intersection with Bleecker Street a small park offering some respite from the surrounding aesthetic and moral decrepitude. And towering over the park – named after a Catholic priest – is a church enjoying an unusually prominent and visible location. A tall tower and baroque facade surmount a somewhat institutional exterior with large windows resembling those of an old-time library or school. A step inside, however, reveals an incredibly extravagant, bright and colorful vision. In a Renaissance-style church interior, innumerable statues surround elaborate marble altars and also line the sides and rear of the nave. Paintings, mosaics and stained glass seem to cover every surface, crowned by a grandiose mural of Our Lady of the Rosary over the sanctuary. It is an exuberant, overflowing Catholicism that can be found only in an Italian ethnic parish – that is, if we ignore certain earlier German, Slavic and even “Irish” parishes of the city.

Now St. Anthony of Padua, a few blocks to the south, may be the oldest Italian Catholic church in Manhattan. Our Lady of Mount Carmel in East Harlem may be the most impressive and important in New York Italian-American history. Yet, I am sure that whenever a New Yorker thinks about an “Italian church” nine times out of ten it is this one. For it is big, lavishly decorated and occupies a very prominent site in a well-known part of town. An area, moreover, that remained a relative safe zone for visitors throughout the high crime decades of the City.

At the time of the founding of this parish, devotion to Our Lady of Pompeii was recent but flourishing. A shrine had been organized in 1875 in Pompeii by a layman, Blessed Bartolo Longo. Eventually a grandiose sanctuary was built there that still attracts pilgrims from all over Italy. In the 1890’s Italian immigrants were flooding New York. The “Saint Raphael Society for the Protection of Italian Immigrants” (an Italian benevolent society), the order of St Charles Borromeo (the Scalabrini fathers) and a wealthy Irish benefactor, Annie Leary (of upper Fifth Avenue), helped organize the new parish in 1892. In 1898 the parish of Our Lady of Pompeii was able to acquire a modest if dignified permanent home. An old Unitarian “temple” (of the same style and era as nearby St Joseph’s Catholic Church) on 210 Bleecker Street had been the home of St. Benedict the Moor – the first parish for black Catholics in New York, organized in 1883. Because of the shift of the black population north, that parish was moving uptown to a new home on West 53rd street. Our Lady of Pompeii moved in. Countess Leary donated the copy of the image of Our Lady of Pompeii that adorned the altar and otherwise continued to provide major support to the fledgling parish. From the beginning until the present day this parish has been directed by the Scalabrinian Fathers. Despite the dedication of the parish, many of the original parishioners came from Genoa. 1)

Strange: the old parishes of New York so often originated in individual initiatives by diocesan or religious clergy, laity and wealthy donors – or in the case of Our Lady of Pompeii, all three together. It contrasts with rigidly centralized top-down management of the archdiocese today! And, as in many other cases, the image currently propagated of the 19th century Church – exclusive clericalism, universal grinding poverty, animosity between Irish and newer immigrants – needs extensive nuancing.

Now the key figure in the era of the parish’s greatest growth was Father Antonio Demo, pastor from 1899 to 1933. He supervised the conversion and decoration of the former church of St Benedict the Moor. Amid many struggles, he managed the massive increase in size of the Italian population in South Greenwich Village:

The Catholic population (of Our Lady of Pompeii parish) of 25,000 shows an increase of 5000 in five years due to emigration and, principally, to naturally growth. During Father Demo’s first year as pastor there were 180 marriages snd 400 baptisms; in 1912 the figures were baptisms 1420 and marriages 468; and in 1913: 1352 baptisms and 432 marriages. 2)

The old church must have been grossly inadequate – but soon relief came from an unanticipated development. In 1923, Sixth Avenue was to be lengthened to the south and Our Lady of Pompeii was squarely in its path. The old church was demolished and Fr. Demo built the present lavish new structure, completed in 1928. It was a combination of church, school, convent and attached rectory. Given the high cost of land in Manhattan, such multipurpose structures were often built in New York City in that era – one thinks of Corpus Christi parish, the recently closed St. Stephen of Hungary or what is now the “Villa Maria.” But none of these are on the scale of Our Lady of Pompeii! Moreover, the tall solitary tower facade recalls vaguely the tall, stand-alone campanile of the original shrine in the “old country.” A parochial school was opened in 1930 staffed by the “Zelatrices” (after 1967, the “Apostles” of the Sacred Heart).3) The bulk of the decoration of the church – high altar, murals and windows – was completed between 1934 and 1941. 4) Regrettably, Father Demo himself did not see most of this: he had effectively resigned the pastorate in 1933 amid worsening economic conditions and died in 1936. 5) The park in front of the church was named after him in 1941.

But after the sacrifices of the first years Our Lady of Pompeii prospered now as a comfortable middle-class parish – until the 1970’s. It’s perhaps a surprise to some that Greenwich Village, along with Stuyvesant Town, remained perhaps the last significant outpost of the Catholic middle class on the island of Manhattan. The exclusively ethnic character of the Our Lady of Pompeii parish gradually eroded: already by 1940 at some masses the sermons were given in English.6)

(Above) Blessed Giovanni Battista Scalabrini, Bishop of Piacenza and the founder of the Missionaries of St Charles Borromeo (the “Scalabrini Fathers”), as depicted in a painting in Our Lady of Pompeii.

![nationalcyclopae14newy_0804[1]](https://sthughofcluny.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/nationalcyclopae14newy_08041.jpg)

(Above) Countess Annie Leary (her title was papal) was a wealthy, exceedingly generous, but strong-willed and often difficult woman. She was a colorful figure in New York society and Catholic charity up till her death in 1919. In addition to her support of various initiatives to aid Italian immigrants (including the founding of Our Lady of Pompeii), she created a Catholic chapel at Bellevue hospital (the magnificent Munich stained glass from that building is still at Bellevue), funded the erection of the statue of Christoper Columbus on Columbus Circle and helped the contemplative order of nuns of St Mary Reparatrix come to New York and take over the parish of St Leo. She is buried under Old St. Patrick’s Cathedral.

(Above) The priest in this stained glass window from the late 1930’s is said to have the features of Fr. Antonio Demo. 7) He oversaw the fantastic expansion of the parish and the building of the present church.

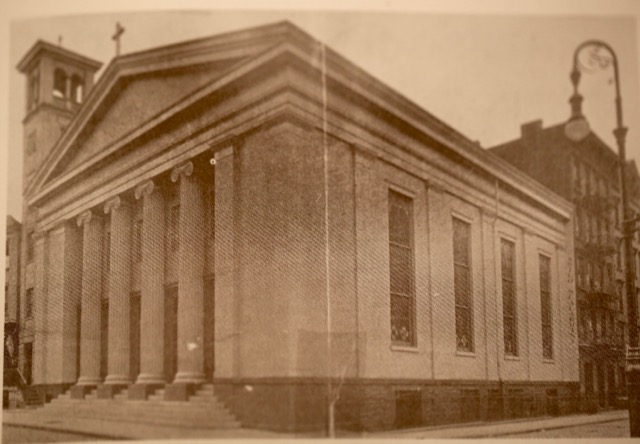

(Above and below) The 1836 Unitarian “temple” on Bleecker street acquired by Our Lady of Pompeii in 1898 from the congregation of St. Benedict the Moor. Already the interior decoration was lavish – if on a much smaller scale than in today’s church. 8)

(Above) The copy of the image of Our Lady of Pompeii above the main altar. According to the parish history, this is the original painting given to the new parish by Countess Leary – if so, it has been cut down to fit this frame. 9)

(Above and Below) These pictures give some idea of the profusion of images in this church. Images of Brazilian and Filipino devotions supplement the original Italian inventory.

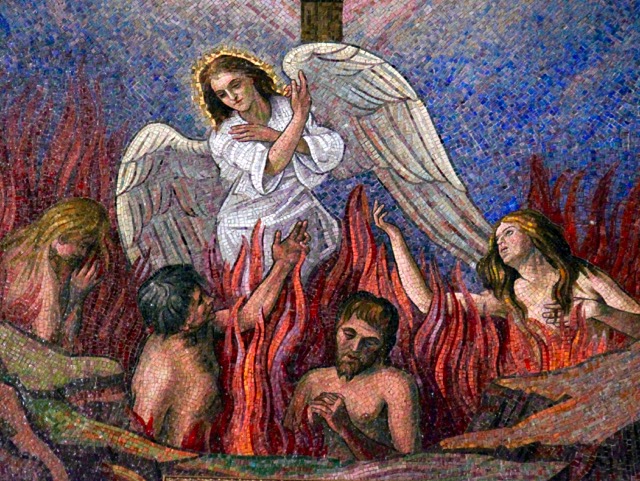

(Above) A sign of today’s Church? This mosaic of the poor souls in purgatory is now ( June 2016) covered by the backdrop for the “image of mercy.” See photograph immediately above this image.

(Above) This image of “religious profession” was added to fill out an eighth window panel in a cycle of the seven sacraments. One of the nuns teaching at the school is supposed to have posed for this window. 10)

(Above and below) Two saints who never fail to appear in Italian parishes! Before 1900, moreover, Mother Cabrini was associated briefly with this parish while organizing a school for Italian girls – naturally, also in collaboration with Countess Annie Leary. 11)

(Above) The main altar – featuring angel-borne electric torches and the the recent insertion of a somewhat startling image of the “Holy Face.”

(Above) The grand mural of Our Lady of the Rosary. (Below) This detail and the inscription refer to the battle of Lepanto.

In the 1970s Our Lady of Pompeii was caught up in the great crisis of Catholicism in New York and the world. The old parishioners steadily moved to the suburbs. The population of the parish took on a profile like so many others in New York City:

– The original parishioners and their descendants, who, although largely residing outside the boundaries of the parish and even of the city continued to return to Our Lady of Pompeii and provide generous support;

– Those marginalized by the relentless, pitiless onward march of life in the capital of modernity: the elderly, the poor, those suffering from various addictions; and

– The new immigrant groups: in the case of Our Lady of Pompeii, Brazilians and Filipinos.

Vatican II, as always, made a major contribution to this crisis. The parish history makes clear that this parish went through a traumatic time particularly between 1970 and 1975. The most dramatic step was the removal and repainting of the mural that is the centerpiece of the church. You see, this painting of Our Lady of the Rosary contained images of the poor souls in purgatory and of the battle of Lepanto that were and are anathema to the Conciliar Church. But then events took a very different turn from those at Our Lady of Pompeii’s next-door neighbor to the north, St. Joseph’s. In contrast to the total housecleaning pushed through there, real resistance emerged at Our Lady of Pompeii. The removal of the mural was but the preface to the pastor’s proposed wholesale restructuring of the sanctuary. A poll was taken of the parishioners and of 220 who responded only 40 chose the option “to change in conformity with Vatican II”; 114 wanted no change at all. Further renovations were stopped. The pastor resigned; indeed, there were a half-dozen pastors of this parish in the period 1964 to 1976. 12) In 1985, amid the jubilation of the parish population,a copy of the original 1937 mural replaced the “Vatican II” version. 13) This is one of the few successful instances of resistance to the so-called Vatican II reforms in New York of which I am aware.

Since then things have calmed down. The parish positioned itself more and more as a “Shrine” of Our Lady of Pompeii transcending diocesan boundaries. An annual Serata Italiana brings back old parishioners and hopefully attrracts newcomers. The parochial school has continued to function: a rarity in New York City parishes. Moreover, in contrast to many others, Our Lady of Pompeii school emphasizes its Catholic identity. The parish played more and more the role of a provider of social services.

And of course there is the steady stream of tourists visiting the Village. Some drop in now and then to admire the decor of this resolutely non-modernist church. It is the extravagant interior – truly Catholic and Italian -that draws them. It captures the overflowing and superabundant nature of grace and of creation. To the many devotions established by the Italian parishioners new immigrant groups have added their own statues and pictures. It is the very nature of Traditional Catholicism as opposed to Conciliar Catholicism: a multitude of paths to the Divinity open to the individual believer, not a exclusive focus upon a priest celebrating the “liturgy” in a bare room. And yet, it’s not a jumble of individualistic caprices, but “it all hangs together” (Eric Gill) in wondrous harmony!

Admittedly, a closer inspection of the statues and the stained glass reveals that, generally speaking, they are not of the absolutely highest quality. As in other lavishly decorated Italian parishes (one thinks of Precious Blood in Little Italy or of Our Lady of Peace) these parishes at first lacked the financial resources of mainstream Archdiocesan parishes and those of religious orders. Then, by the time funds did become available for more ambitious programs of decoration, the quality of Catholic religious art had already started to decline. But the overall impression is magnificent: what sacrifices must have been made to achieve this decoration and, even more so, to restore and preserve it!

(Above) The 1975 “Vatican II” painting in the apse, as seen in a photograph from 1980. 14)

If I am not mistaken, in the recent past more concrete elements of tradition long thought dead also have reared their head. The words of the pastor in the church bulletin are eminently solid. A course in traditional artistic techniques has been offered at the parish. And even a Solemn Traditional Mass was celebrated at Our Lady of Pompeii. Does this indicate the opening of an unexpected path to the evangelization of the neighborhood of this parish? Building on the great legacy of the past but moving beyond nostalgia and folklore, does the fullness of Tradition offer a way to establish contact with the many non- or even anti-Christians who now dwell in affluence where impecunious immigrant Italians did generations ago? For it is clear that the other path (adopted by Our Lady of Pompeii’s next door neighbor, St. Joseph’s in the Village, in the 1970s) of accommodation to the mores of the neighborhood, the city and of the “American Catholic Church,” led in the end nowhere.

I would be the first to admit that a project of evangelization in this area and at this time indeed would require a “leap of faith!” But with God all things are possible – and wasn’t the beginning of this parish – for different reasons – a challenge to evanglization too? Fortunately, thanks to the sacrifices of prior generations, Our Lady of Pompeii has a beautiful church and a functioning parish with which to start.

(Above and below) These statues of Our Lady and St John are of a different style and of a higher artistic quality than the rest of the decor. Originally part of the furnishings of the church of St. Benedict the Moor, they were removed to that congregation’s new church in 1898. In 1979, when St Benedict the Moor’s interior was being “renovated” they were handed back to Our Lady of Pompeii. They now share space with more recent devotional images. 15)

(Above) The two statues in the previous photographs once flanked this crucifix, which, like them, is of higher artistic quality than the rest of the church decor. The crucifix was bequeathed by the parish of St Benedict the Moor to Our Lady of Pompeii in 1898. It has been located in this shrine in the new church of Our Lady of Pompeii since the 1920’s. 16 )

(Above) It’s hard to restrain Catholics practicing traditional devotions….

See the parish website – featuring a virtual tour of the church! There is an exceptionally fine parish history by Mary Elizabeth Brown: From Italian Villages to Greenwich Village: Our Lady of Pompei 1892-1992 ( Center for Migration Studies, 1992, New York). See also, by the same author: The Italians of the South Village (The Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation, 2007, New York)

1) Brown, From Italian Villages at 15- 19, 21-23

2)The Catholic Church in the United States of America, Vol. 3 at 360. (Catholic Editing Company, New York 1914)

3)Brown, From Italian Villages at 82-86;88-89.

4)Brown, From Italian Villages at 103-104, 106-107.

5) Brown, From Italian Villages at 98-99.

6)Brown, From Italian Villages at 110-11. The parish history helpfully adds “In 1940, all masses were in Latin.” Ibid. at 111.

7) Brown, From Italian Villages at 107.

8) Brown,From Italian Villages at 11.

9) Brown, From Italian Villages at 89.

10) Brown, From Italian Villages at 107

11) Brown, From Italian Villages at 25; Brown, The Italians of the South Village at 50.

12) Brown, From Italian Villages at 143-47.

13) Brown, From Italian Villages at 163-64.

14) Brown, From Italian Villages at 136.

15) Brown, From Italian Villages at 154-55

16) Brown, From Italian Villages at 155.

Related Articles

No user responded in this post