Photograph of 1900 showing the noted Minnesota artist Nicholas Brewer working in his St. Paul studio on a portrait of Fr. Thomas J. Ducey of St.Leo’s. 1)

St. Leo (and the convent of Marie Reparatrice)

12 East 28th Street

For connoisseurs of New York of churches, St. Leo of East 28th St, founded in 1880 and completed in 1881, has been a tantalizing enigma. For, seemingly alone among the almost innumerable parishes established in that era, St. Leo’s seems to have “disappeared” not even 30 years after its foundation, despite its location in a originally well-to-do neighborhood. The conventional wisdom is that this was a minor initiative, a kind of chapel associated with one particular priest. After his death, so the story goes, the parish was transformed into a convent and disappeared from public view. Then this convent with the remaining parish buildings in turn vanished in the 1980s.

Additional research tells entirely different tale. The parish of St. Leo’s enjoyed a citywide and even national reputation around 1900. And, after its transformation into a convent in 1909, the public visibility of this church – at least in New York City itself – actually increased.

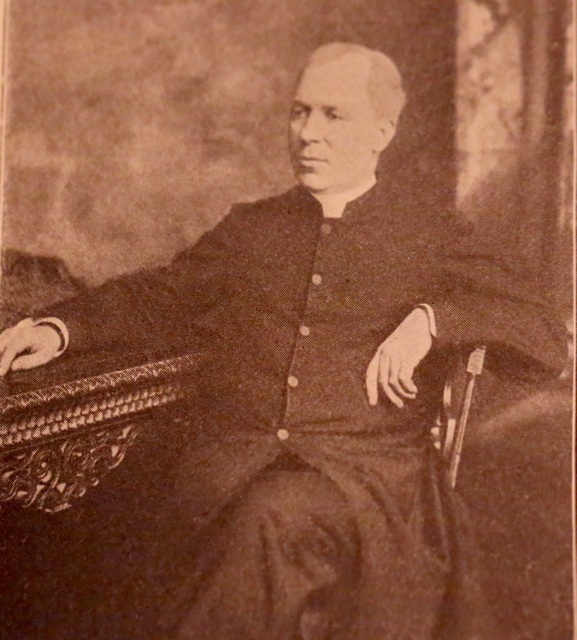

St. Leo’s from the beginning was closely associated with its founder: the charismatic Fr. Thomas J. Ducey – indeed, by his death it was known simply as “Fr. Ducey’s church.” He was one of the seemingly inexhaustible number of remarkable clergy and laity that distinguished the New York Archdiocese in its golden age between 1880 and 1930. He founded the parish in a part of the city that at the time was a distinguished residential district of the wealthy yet lacked a Catholic church. From then until his death Fr. Ducey and St. Leo’s where indistinguishable. It was one of the smaller “non-ethnic” parishes of the archdiocese, with a congregation of 2,000 at the time when many parishes (like the parish it had been carved out of, St. Stephen’s) had 20,000 or more parishioners. 2)

The founding pastor was indeed remarkable in a number of respects.

First, he was at ease hobnobbing with the rich and famous. By inheritance he had acquired some personal wealth of his own. It is claimed that the building of St. Leo’s was largely facilitated by Lorenzo Delmonico of the famous restaurateur family (Fr. Ducey was a boyhood friend of the family; the Delmonico family was active in the foundation of several other Catholic parishes over the course of many years) 3). Fr. Ducey was a regular at Delmonico’s – the premiere restaurant in New York – and has been described as the house chaplain of the Delmonico family. 4) Within his parish boundaries were numerous wealthy families: the Delmonicos of course, but also the Iselins, Clarence Mackay, John McCormack etc. Fr. Ducey officiated at society marriages and presided at the funerals of the rich and famous.

Second, he was a strong advocate of justice for the workingman. This earned him nationwide notoriety. In this he was following some of the views of the redoubtable Fr. Edward McGlynn, the pastor of neighboring St. Stephen further to the east on E. 28th St.

Third, what perhaps made him most famous among his non-Catholic contemporaries was his charity towards those who had fallen on hard fortune. Many of the parishioners were in fact not the proprietors of splendid mansions but those who worked in them or in the neighborhood’s growing number of hotels. For the immediate vicinity of St. Leo’s became more and more a district of hotels such as the luxurious hotel Seville next door and the old Waldorf Astoria up Fifth Avenue. Yet at the same time there were many impoverished transients. New York City at the time was filled with those in temporary quarters: immigrants, laborers and those hard up on their luck. That included the formerly wealthy in one difficulty or another. Fr. Ducey adapted to the changing surroundings of his parish and reached out to this population. For example, we learn that he helped out the famous photographer Matthew Brady who had fallen on hard times. Fr Ducey assisted penniless actors and – unofficially – acted as chaplain to Catholic actors at a time when that apostolate was frowned upon. But his most remarkable initiative was the creation of a room of repose, distinctly Catholic in appearance but open to those of all denominations (including Jewish), where those who had died abandoned in hotels or lodgings could receive a decent burial service. His motivation was ecumenical; the Catholic “stranger dead” already had been housed in the lower church of St. Leo’s – the house of repose was intended to deal with plight of the deceased of another or even of no church. Indeed the building was constructed in cooperation with members of protestant churches and the synagogue. 5)

When Fr. Ducey died on August 22, 1909, he left his not inconsiderable fortune to St. Leo’s parish. But, like so many other parishes at this time, St. Leo’s resident parishioners had largely disappeared. At this moment, however, Providence intervened.

(Above) Fr. Thomas J. Ducey.(this photograph and the following 5 images come from an 1899 article on St. Leo’s by Alice Waring in Metropolitan Magazine.)

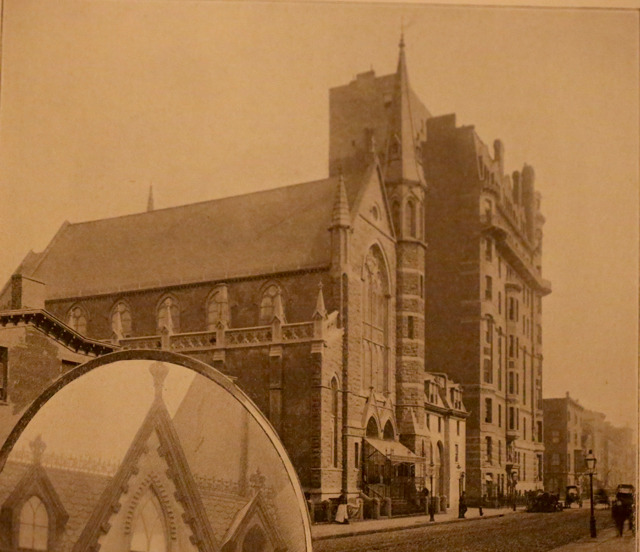

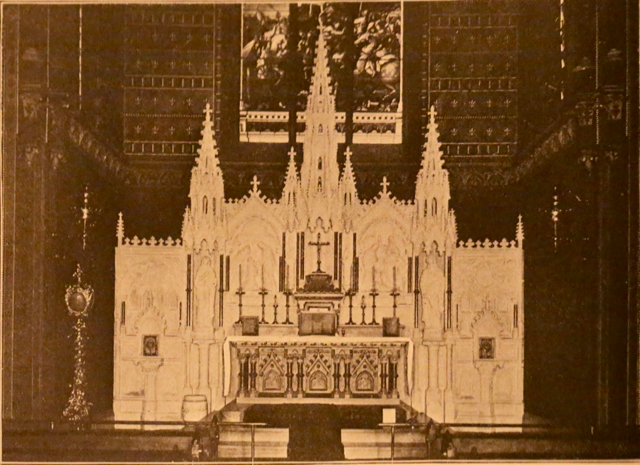

(Above) St Leo’s as it appeared in 1899. The large building to the east is typical of how the parish’s neighborhood was being transformed in that era; within a few years it too would be replaced.(Below) The interior of St. Leo’s in 1899.

I believe the stained glass depicts the encounter of Pope Leo the Great with Attila the Hun which, according to legend, saved Rome. The magnificent furnishings of this church – artistically similar to those of nearby St Stephen’s – demonstrate that for Fr. Ducey too, the creation of a beautiful, unapologetically Catholic church was a necessary element of evangelization.

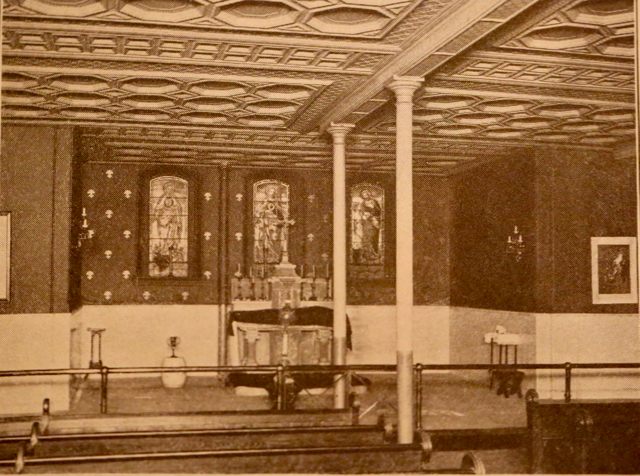

(Above) The lower church of St. Leo’s in 1899.

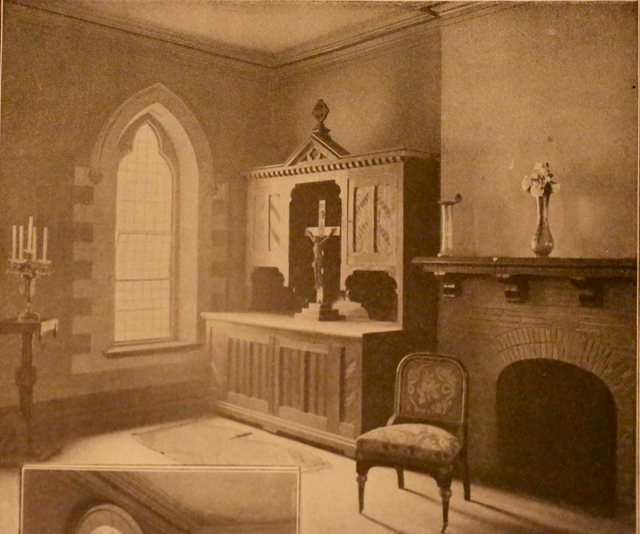

Two views of the “House of Repose” in 1899. (Above) The Robing Room; (Below) the Repose Room itself.

We have already covered the many initiatives of the indefatigable Countess Annie Leary. In 1907 she had facilitated the arrival in the United States of three sisters of the order of Marie Reparatrice (or “Mary Reparatrix”). It had been founded in France in the 19th century primarily to offer adoration of the Eucharist. This order combined the contemplative life with certain active apostolates: giving Ignatian retreats to women, providing training to Spanish-speaking people etc. The sisters had a difficult time getting an acceptable permanent residence in New York – it was hard dealing with their domineering benefactress and an initially unenthusiastic Archbishop Farley.

But then Thomas H. Kelly, a wealthy man whose wife had connections with the Marie Reparatrice order, wrote to the Archbishop after Fr. Ducey’s death and offered to finance the establishment of the order at St. Leo’s. On October 2, less than 2 months after Fr. Ducey’s death, Archbishop Farley agreed to cede the church to the sisters. But the archbishop declared himself pastor for a year and would administer the church through his vicars (at some point the clergy of St. Stephen’s took over spiritual affairs of St. Leo’s) Moreover, he retained the Sunday collections for himself to pay off the parish debt and finance repairs structural improvements. The deed was done and the sisters moved into the rectory of St. Leo’s. 6) A grille was soon added to the church.

The connections of this parish with high society were not broken; indeed they seem to have intensified. Early accounts speak admiringly of the alleged high social status of some of the nuns who are also commended for being able to communicate with the representatives of high society. Through the 1940s we hear of a seemingly endless series of fundraising events for the convent involving distinguished members of politics and society.

Now it is evident that St Leo’s continued to function as a public place of worship. Indeed, the convent attracted a large following for the public adoration of the sacrament – there were always people in the church. The nuns were present before the sacrament from 7 till 5, always in pairs (there was perpetual adoration Thursday through Friday). By 1912 there were 14 nuns and their contemplative life began to exercise a certain fascination on the minds of New Yorkers. 7)

Other aspects of the nuns’ apostolic work blossomed. In 1917 a grand prayer service for women was held at Saint Leo’s. In 1940 a special Novena held in contemplation of the worsening world situation attracted 30,000 to St. Leo’s. 8)

There are numerous references in the contemporary press to the presence of these nuns in New York with their distinctive blue and white habits. It didn’t hurt publicity that the convent was the next-door neighbor of the Seville hotel, prominent in its day. Perhaps most remarkable is a dramatic and romantic 1939 description in The New York Times by Meyer Berger.

“Thursday evening services were closing. Held by the gleaming white tapers, by banks of dancing votive candles and row upon row of novena lights that were steady flames in tall ruby lamps we fell thrall to the organ tones, to the clear voiced invisible choir. The music came from somewhere behind us, deep in the church, as from someplace remote…Inside the golden choir enclosure knelt the sisters… the lights from the altar touched all their features with a faint, rosy color. Every one motionless.

The scene was one for the brush of some medieval master. Only the soft pealing notes of the organ, the hidden choir’s song after Benediction edged it with life….

Behind us and off to the right a young girl in mourning leaned on the pew rail, eyes steadfast on the altar, rosary beads in white fingers.

(After the benediction) We sat for a long time held by the spell. We knew the soft highlights in the altar frame. We stared upon the altar’s whiteness till it blurred; until the tapers’ gleam shifted or seemed to shift. No sound intruded here. This might have been a dream.

People of all faiths come to witness the ceremony of the Adoration, and people from far places.” 9)

It seems incredible to our ears: Eucharistic Adoration as a citywide and ecumenical attraction. But so it seems to have been. Would the church in New York have prospered more if she had had more such places of silent contemplation? The seemingly thriving church of that time was rich in priests and laity of the active life. But there was only one contemplative order in Manhattan – and even the sisters of Mary Reparatrix were really “semi-enclosed”. By 1939, Meyer Berger informs us, there were 36 sisters at St. Leo’s.

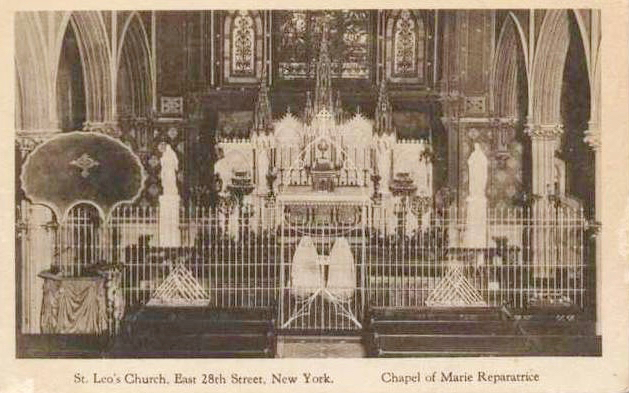

(Above ) A later view of the sanctuary of St. Leo’s, now furnished with a grille for the sisters of Marie Reparatrice. 10) (Below) This photograph, showing two nuns in adoration before the Eucharist, must have been widely disseminated – the version below is of a postcard recently auctioned off in France. It also shows much more elaborate stenciling and painting of the altar compared to 1899.

(Above) This later view – also showing two nuns in adoration – comes from a 1956 postcard. It shows new artwork in a kind of “Beuron” style. 11)

The details of this church’s history after the Second World War are unclear to us. In the 1952 a large new convent was built. In 1966 we read “On East 29th street there’s a convent with 37 happy nuns, 15 of whom are in training as Girls Scout leaders.” It was, after all, the era of the “Singing Nun,”the “Flying Nun” and “The Trouble with Angels.” At this date, however, the sisters still wore their habits and remained semi- enclosed.12) But in the wake of Vatican II the order of Mary Reparatrix suffered the same fate as almost all her sisters:

“Vatican II and its reforms soon touched the congregation…the Church suppressed the “semi-cloistered” character of the congregation and invited sisters to ongoing formation, to apostolates outside of the house…a difficult period that Sr. Mary (a provincial of the order) referred to positively in these words: “A marvelous time of chaos, of re-creation.” …Later, another step was taken in New York (by Sr. Mary) with the closure of the church of St. Leo and its ensuing demolition….13)

The buildings were razed in 1985. But a deal with a developer fell through and the property could only be sold in 1997 – for $15 million,. An enormous, 48 story apartment building and its courtyard now occupy the site of the St. Leo property. 12) Yet, is this not a further example how the Catholic Church leaves its mark on the City – but now in an entirely negative sense? For it was the order of sisters, focused like the developers purely on financial return, that made possible the building of an entirely out of scale apartment building, which completely dominates the neighborhood. So the Anglican “Little Church around the Corner” and Marble Collegiate Church (where Dr. Norman Vincent Peale sounded off for decades) still remain; the Catholic member of this “Trinity” has disappeared. Decades of public Catholic witness had come to an inglorious end.

(Above) St Leo’s today: the grossly disproportionate building in the left background occupies the site of St. Leo’s church and the later convent.

(Above) To help New Yorkers get oriented: the nearby Marble Collegiate Church on Fifth Avenue and E. 29th Street. In the background to the north the Empire State Building towers; in Fr. Ducey’s day this was the site of the Hotel Waldorf-Astoria.

(Above) The courtyard is the site of St. Leo’s church.

(Above) Overlooking this courtyard to the east is an annex of the old Seville hotel built already in 1906 during Father Ducey’s time.

(Above) The entrance to the apartment building on E. 29th street (Below) Directly across the street is the quaint Anglican parish of the Transfiguration (“the little church around the corner”)

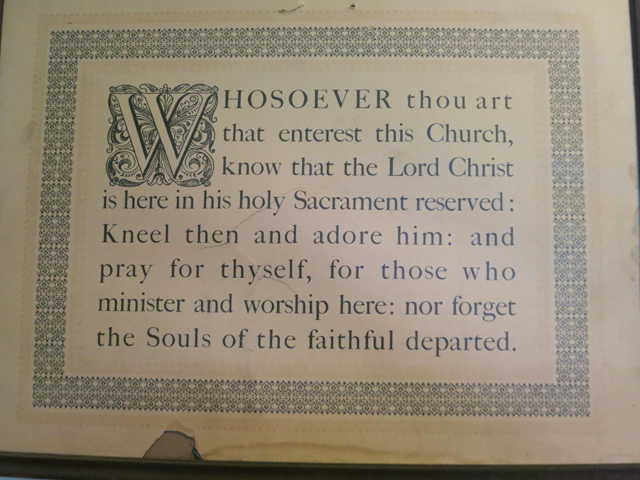

I can’t resist this picture of an ancient notice in the church of the Transfiguration: How many visitors today pay attention to the admonition in this church – or, for that matter, in many Roman Catholic ones?

1. http://forgottenminnesota.com/2015/03/artist-nicholas-brewer/ (Photo courtesy of Minnesota Historical Society)

2. On the construction of St Leo’s see generally: The Lost St. Leo’s Church – No 12 East 28th Street (July 24, 2014). http://daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com/2014/07/the-lost-st-leos-church-no-12-east-28th.html. The author includes other photographs and curious anecdotes of the history of the church.

3. Thomas, Lately; Delmonico’s: a Century of Splendor at 173 (Boston, Houghton Mifflin Company, 1967).

4. Thomas, Op. Cit. at 219.

5. Waring, Alice E.; “A Repose for the Stranger Dead” in Metropolitan Magazine (December, 1899 at 588-592.)

6. Sisters of Marie Reparatrice, New York 100 Years: It’s beginning to Feel like Home (2012)

7. “Service of Perpetual Prayer in the Heart of New York,” The New York Times (October 6, 1912)

8. NOVENA FOR PEACE IS STARTED HERE; Nuns Begin Nine-Day Vigil With Solemn High Mass at St. Leo’s Church; The New York Times (June 23, 1940).

9. Berger, Meyer, “About New York,” The New York Times, (November 6, 1939)

10. Collection of the Museum of the City of New York from “The Lost St. Leo’s Church” supra.

11. http://www.nycago.org/Organs/NYC/html/MaryReparatrix.html

12. “15 Nuns training as Scout Leaders” The New York Times (October 30, 1966)

13. “Mary Piancone, Mother Mary of the Blessed Sacrament 1930-1994, at 160-161.

14. Gabarin, Rachel, “Residential Real Estate; a 48 Story Tower for a Low-rise Neighborhood,” The New York Times (September 18, 1998)

Related Articles

No user responded in this post