St. Ignatius Loyola and St. Lawrence O’Toole

980 Park Avenue

The austere gray neo-renaissance facade of the church of St. Ignatius Loyola blends well with the anonymous, uncompromising canyon walls formed by the apartment buildings of Park Avenue. It exudes the same reserved, off-putting attitude that once characterized the mainly Protestant economic elite of America. Inside the church, in contrast, we encounter a “Catholic” burst of color, mainly gold, covering the walls and ceilings of an interior in the Italian Renaissance style. Yet, on closer examination, this too lacks the decorative exuberance of many other Catholic churches of that era. Very expensive but cold marble and mosaics cover walls, baptistery and sanctuary. The magnificent golden metalwork of the railings, sanctuary lamps and pulpit gleams brightly. This is St. Ignatius, the main church of the Jesuits in New York City.

But this cold grandeur was not always so!

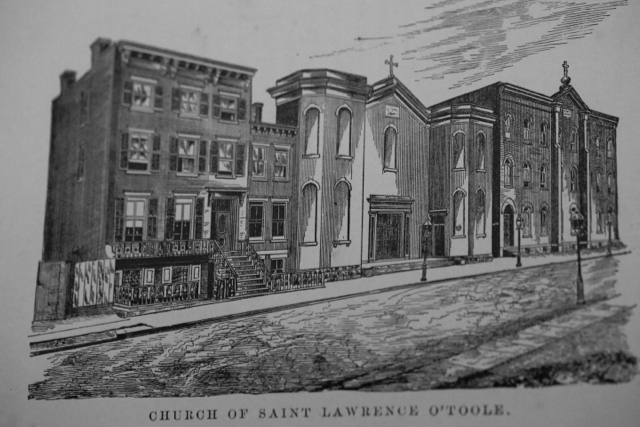

In 1851 a parish arose on the upmost fringes of New York City in what was at that time a distant village: Yorkville. That area included all the territory later considered part of the Upper East Side. 1854 a modest church on East 84th street was dedicated: “with the smoke of incense and the aspersion of holy water, the church was blessed under the invocation of St. Lawrence O‘Toole.” ( a 12th century bishop of Dublin). Archbishop Hughes preached, taking as his text Apoc. xxi 1-3: “and I saw a new heaven and new earth. … And I John saw the holy city, the New Jerusalem, coming down from heaven from God, prepared as a bride for her husband. And i heard a great voice from the throne saying: Behold the tabernacle of God with men, and he will dwell with them and they shall be his people; and God himself with them shall be their God.” 1)

(A little further, at Apoc. xxi 5, we read: “Behold I make all things new.” In 1854 the Archbishop of New York cited Revelations for building new churches – not closing them)

The Jesuits had been visiting the islands adjacent to Yorkville early on. The Jesuits came to exercise a ministry to these outcasts of the “periphery,” as the expression goes nowadays. First, there were the quarantined sick. (As one early Jesuit put it: other missionaries are like hunters who have to pursue their game, here the police drive the game to the missionary.) Second, and even more importantly, they took over the spiritual care of the home for “fallen women” in the care of the Good Shepherd sisters. Their duties at the convent included “confessions for the sisters, the Magdalenes, the penitents and the Perseverance class.” To reach the convent, the Jesuits had to travel north from their New York center at St. Francis Xavier in Chelsea far to the south. Given the transportation of the time the journey was very wearisome – so in 1866 the parish of St. Lawrence O’Toole was given to the Jesuits. 2) A former pastor of St. Ignatius has claimed that the Jesuits in fact “conspired” with the last Archdiocesan pastor of St Lawrence O’Toole – who had been a Jesuit and now returned to the order – to achieve this ‘takeover.” 3)

And then began an almost incredible change of circumstances. The center of New York wealth moved steadily northward along Fifth Avenue. Splendid mansions rose up along its length; the side streets and adjacent avenues flourished as well. St. Lawrence O’Toole parish, which had started as an outpost on the fringes of the city, by the 1890’s found itself in the midst of the wealthiest neighborhood in the United States, perhaps the world. Only the story of the surroundings of St. Patrick’s cathedral is comparable. The Jesuits of St. Lawrence O’Toole were active in the rapid buildup of Catholicism in Yorkville and what began to be called the Upper East Side – for example, they were directly involved in the organization of the German parish of St. Joseph.

A new church was required, reflecting the growing splendor and population of the neighborhood. At first, a Gothic style edifice was planned. Work was begun in 1884 but came to a halt in 1886. When it resumed in 1895, a new, grander design was adopted in the new style of that era: the classical/baroque/ renaissance idiom of the fashionable beaux-arts movement. The architects were Schickel & Ditmars (known at that time for executing numerous commissions for the Catholic Church, including Dunwoodie Seminary and the nearby churches of St. Joseph in Yorkville and St. Monica). The new church was dedicated in 1898 – the installation of the furnishings, mosaics and windows continued for years. In 1898, the upper church was dedicated to St Ignatius Loyola; the lower church to St. Lawrence O’Toole. Technically, since that year this parish has been under the joint patronage of these two saints. 4) Around St Ignatius church a whole complex gradually arose: a parochial school, a high school and associated structures. It was similar, in that regard, to many other parishes of that day – both those of the archdiocese and those of the religious orders – but on a more lavish scale.

(Above) The original church of St. Lawrence O’Toole (From Gilmary, The Catholic Churches of New York City(1878))

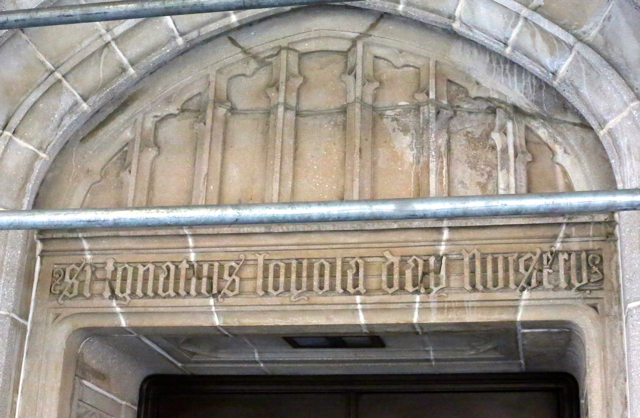

(Above) The transition from the buttresses of the original gothic plan of 1884-86 to the beaux-arts design of the completed church. (Below) The Roman beaux-arts grandeur of the facade. But two towers that were planned were never completed. Undoubtedly, as at St Vincent Ferrer, it was felt that any towers or spires would be dwarfed by the multi-story apartments rising up around these churches.

(Above) The nave and sanctuary and (below) a side aisle in Renaissance style.

(Above) St. ignatius Loyola; (below) St. Lawrence O’Toole. The two patron saints of the parish depicted in windows formerly in the lower church.

In 1906 the mixed choir of St Ignatius church was disbanded because of the Motu Proprio of Pius X on liturgical music. As a consequence in 1907 the boys’ choir was instituted. It soon attained citywide renown. (Similar developments took place at St Patrick’s Cathedral and St. Vincent Ferrer). 5)

Then came two special institutions.

Before World War I, St Ignatius Loyola parish straddled two worlds – that of the rich near Fifth Avenue, and across Park Avenue (and its railroad tunnel), that of the working class. In 1910 a day nursery was founded for the struggling working mothers of the parish. And then: “the sympathy of Mr. Nicholas Brady was enlisted in the work (of the day nursery) and, as he is accustomed to big things, his sympathy took on big proportions.” Brady (1878-1930) was a prominent businessman and Catholic philanthropist represented on the board of many American corporations. He purchased a new site at 240-42 East 84th street and in 1915 erected magnificent five-story building “fitted with every requisite for a day nursery.” It included originally an “exquisite” chapel. The only condition imposed by the donor was “that none shall be denied the use of its facilities on account of race, creed or color.” 6)

(Above and below) St. Ignatius Loyola’s day nursery.

Second, in 1914 Regis High School for boys opened its doors nearby. It had both high requirements for admission and free tuition – features it retains to this day. In fact, Regis High School is probably today what most New York Catholics think of when St Ignatius Loyola parish is mentioned. Not so well known, however, is that it too originated from a single donor’s initiative and generosity: Julia M Grant, widow of New York mayor and businessman Hugh J Grant. The family of Julia Grant continued supporting Regis financially for decades afterwards. This family involvement may partially account for the radically different course – regarding quality and finances – taken by Regis compared to most other Catholic schools of the area. 7)

In 1916 the Jesuits celebrated their first fifty years at St. Ignatius Loyola and St. Lawrence O’Toole. Henceforward the Jesuits’ mission became increasingly the polishing and perfecting of what had been created rather than the launching of new initiatives. The schools consolidated their reputations and acquired new facilities. The church received in the 1920’s magnificent new metalwork.

But, from the perspective of economic demographics, the luck of the Upper East Side Jesuits only increased. Through the 1920’s arose the endless wall of luxury apartment buildings that line Park Avenue. And, after the Second World War, what remained of old Yorkville “on the wrong side of the tracks” commenced its gradual transformation from working and middle class to a much higher income stratum. In fact, until the 1960’s the only fly in the ointment – other than negotiating the perils of the Great Depression – was the carve out of the new Archdiocesan parish of St. Thomas More in 1950. Cardinal Spellman undoubtedly wanted to share more directly in the Upper East Side glory!

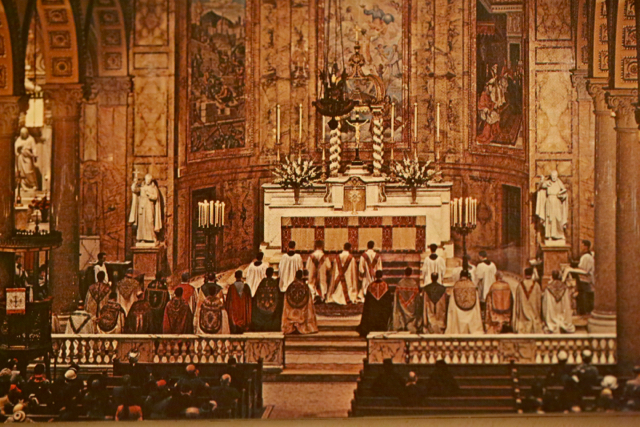

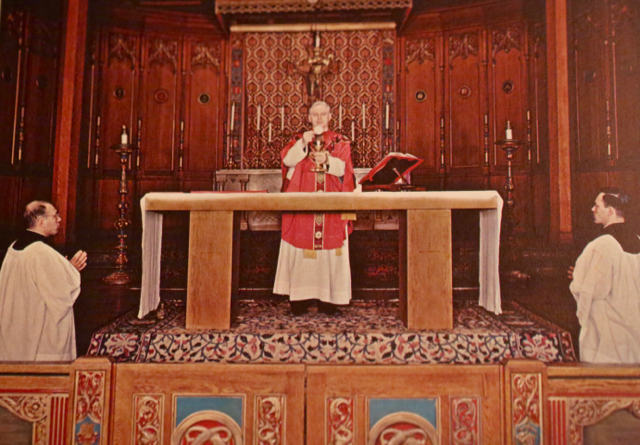

And in 1966 the parish issued a slim follow-up volume to Dooley’s original parish history: The Jesuits in Yorkville 1866-1966. 8) It is a curious monument to a “Catholic milieu” which, within a few years, would utterly disappear. In this volume we still find talk of patriotism, anti-communism, sodalities, campaigns against pornography and conversions – and a photograph of a grand benediction in the presence of 20 copes. But we also read of ecumenism and aggiornamento, see a photograph of the mass celebrated “versus populum” and hear that attendance at the parochial school is declining.

The Old and the New. (Above) Forty hours devotion closing ceremony in 1966; (below) mass “facing the people” in the lower church.

(Both from The Jesuits in Yorkville 1866-1966).

At that time, the Jesuits stationed at the Upper East Side still engaged in a multitude of apostolates and ministries across New York City – including what had brought them to Yorkville in the first place: acting as chaplains to the island hospitals. (The Jesuits had had to give up their other early apostolate in the area, the chaplaincy of the convent of the Good Shepherd sisters, as early as 1892)

Related Articles

No user responded in this post