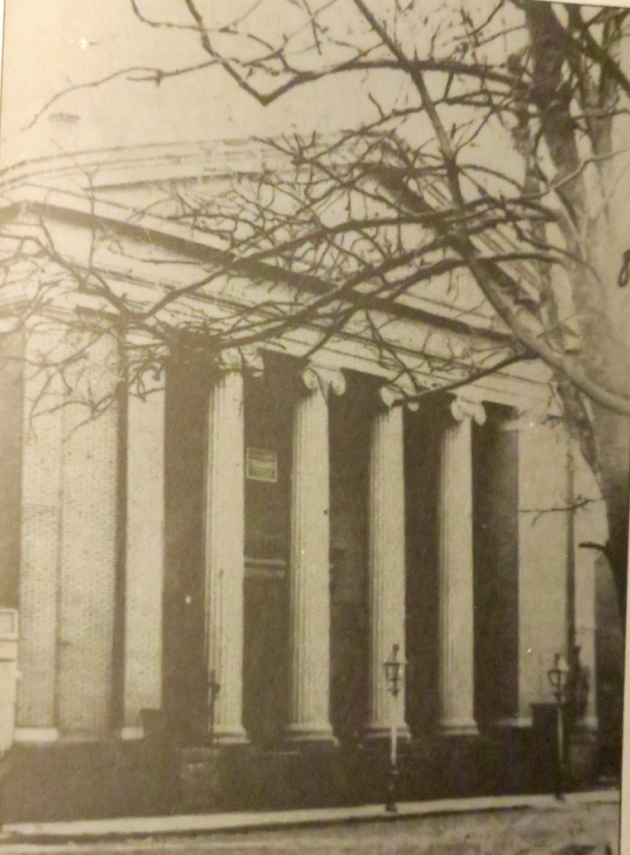

(above) St Benedict the Moor in happier times.

St. Benedict the Moor

342 West 53rd Street.

One day in 2014, I stopped by the curious, unpretentious church of St Benedict the Moor. In several prior visits I had never gained access to the main church (weekday masses were held in the rectory chapel). But on this day, I found the church open and filled with a large congregation! The Blessed Sacrament was exposed in a monstrance upon the altar; the people were singing and praying the rosary. Someone mumbled to me something about a “parish festival.” I decided it was high time for me to come back on some Sunday when the church would be less crowded, take some pictures and write something about this time-honored legacy of past evangelical effort and sacrifice – the first church for blacks in the Northern states!

But when I returned – the following Sunday, I believe – the church was closed and locked the rectory of the Franciscans abandoned (the priests had moved to New Jersey), all religious services discontinued.

Had I actually attended the final celebration of the life of this parish?

St Benedict the Moor has an extraordinary history quite in contrast with its resolutely pedestrian un-Catholic appearance. For this parish was founded as a first mission to the blacks of the New York Archdiocese and beyond. It owes its origin to a bequest by Fr Thomas Farrell, the renowned rector of St Joseph (Greenwich Village – at that time most New York blacks lived in or around the Village). The equally well-known Fr. Richard L. Burtsell was the founder and first pastor in 1883. The first home of the new “mission church to the colored people”– a then out-of-fashion neoclassical temple – later served as the first church of Our Lady of Pompeii. St Benedict the Moor actually had no territorial boundaries but included all the black population of New York and even of the Newark and Brooklyn dioceses as well.

In 1898 the church we see today on West 53rd street was acquired from a German Protestant congregation. For by 1900 the center of gravity of the New York City black population had moved north to the West 50’s. We read, however, that in fact whites made up a large part of the congregation throughout this period – and provided much of the financing. The surroundings of the parish’s new home were indeed not stylish – in those days an elevated rail line ran down West 53rd street.

In its early years this mission generated an extraordinary amount of commentary – often hostile – from the New York and national press and the Protestant establishment. Was it not a nefarious plot to establish a papist fifth column in a new section of the population? Nor can we say that this mission met with understanding and enthusiasm among all quarters of the Catholic population. Yet through the 1930’s a handful of dedicated (Irish) priests dedicated themselves with heroic devotion to the mission of St Benedict the Moor: Fathers John F. Burke (the second pastor, who in 1907 became leader of the national Catholic mission to blacks in the United States), Thomas O’Keefe and Timothy Shanley. In the course of time an orphanage, a school (which St Katherine Drexel visited in 1924) and a convent of sisters were added to the parish.

(Above) This neoclassical temple was the original home of St Benedict’s parish – and later of Our Lady of Pompeii.

(Above) The festive liturgy for the Golden Jubilee of the parish, 1933.

In 1933 a grand Solemn Mass was the highlight of the parish’s fiftieth anniversary. Yet in a few short years difficulties came to a head. The blacks of New York, the target group of this mission, had for the last thirty years been relocating uptown once again – to Harlem. If whites worshipped at St Benedict’s, Catholic blacks could and did worship in their local territorial parishes, in Harlem or elsewhere. Finally, the relentless transformation of the immediate Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood into a heavily commercial zone hurt the local parishes, including St Benedict the Moor. By the late 1930’s it had been reduced to a chapel of the nearby parish of Sacred Heart, with only Sunday masses being offered.

But in those days Catholics did not so easily give up their consecrated churches, regardless of “demographic change.” Was there not an infinite number of evangelical works still to be accomplished? After the Second World War it was now the Spanish- speaking peoples – particularly the Puerto Ricans – who started to flock to New York. Cardinal Spellman’s advancement of the Spanish-speaking apostolate has been regrettably forgotten nowadays. Yet due to him, St Benedict the Moor was “repurposed” as a Spanish-speaking mission parish, in the care of the Third order Regular Franciscans. This too was commemorated by a splendid liturgy in February 1954. So, St Benedict the Moor’s mission of evangelization continued for many more decades. By the 1980’s, however, except for parishes mostly in the Yorkville/Upper East Side area, almost every parish on the island of Manhattan had a large “Hispanic” population.

The rededication of the parish to the Hispanic apostolate in 1954.(Above)Cardinal Spellman in procession. (Below) The liturgy celebrated on this occasion – which was also reported in the New York Times among other places.

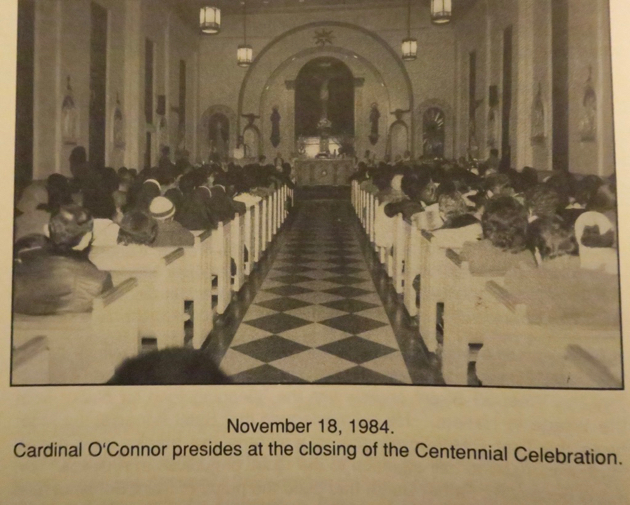

(Above) Mass with Cardinal O’Connor in 1984.

(Above) The new rectory was dedicated in 1967 – it stretched the resources of this small parish.

The layout of the church of St Benedict the Moor, built in 1869 as a severely Protestant hall, would strike most as unusual for a Catholic parish. Upon entering, the visitor encountered downstairs a large bookstore. To get to the actual church one had to ascend a staircase. The church regrettably was locked on weekdays – a not infrequent phenomenon in Manhattan. The visitor could get only a glimpse through glass doors of a simple, obscurely lit interior adorned with some statues and stained-glass windows (the decor of the sanctuary apparently dates from a 1950’s restoration).

(Above) The interior of the church – reached by a flight of stairs. (Below) Part of a large window or Our Lady of Guadalupe added in this parish’s “Hispanic” era.

(Above and below) The forlorn church of St Benedict the Moor as seen in more recent months.

St Benedict the Moor made its way on to Cardinal Egan’s hit list in 2007. Yet the outcry was such that Cardinal had to back down. It is eloquent testimony to the accelerating decline of Roman Catholic sensibility in New York that in 2014 St Benedict could be shuttered summarily – even outside of the normal “Making all Things New” process – with nary a peep from anyone. St Benedict’s has now (2017) been made available for sale or other uses; some (secular) opposition to the loss of the church is now stirring in the Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood.

St Benedict, while it still stands, testifies to earlier generations that acknowledged and took up the burden of evangelization in this gigantic metropolis. Like so many other seemingly minor New York parishes, in its heyday it attracted citywide and even national attention with a mission that extended far beyond the parish’s immediate neighborhood. But the significance of the summary closure of this church is not just the tragic loss of an inheritance of the past. It’s a most eloquent symbol of the extinction of the spirit of Catholic mission in the New York Archdiocese.

(Above) Behind an iron grate the relic of a former devotion.

(Above) The statue of Our Lady, located in a niche obove the rectory door, has been removed.

See generally, Coll, Fr. George, A Pioneer Church (1993); O’Brian, Michael J., St Benedict the Moor: Mission Church of the Colored People (1933)

Related Articles

1 user responded in this post