What really distinguishes St. Paul’s from other Catholic churches of the era is the magnificent surviving decoration by the noted artists of the era 1890-1920. 1)We should start with the stained glass and painting of the (Catholic) John Lafarge. His non-figurative windows glow with rare deep blues and yellows. These are joined by several fine English and German stained glass windows in the apse. LaFarge provided the first color decorative scheme of the interior. He also contributed a painted “Angel of the Moon ” in the apse; the companion “Angel of the Sun ” was never executed by him but a study survives. 2) He also is credited with designing some of the side altars ( but were these more likely designed by his son’s firm, Heins & Lafarge?).

(Above and below) Nonfigurative windows of John LaFarge – along with Louis Comfort Tiffany, the premier American stained glass artist of that time.

(Above) The “Angel of the Moon” mural in the apse. (Below) Lafarge’s draft for the “Angel of the Sun” ( Staten Island Museum) ( William Laurel Harris later painted that angel in St. Paul’s)

The second major decorator was William Laurel Harris, who covered the church with murals and stenciled designs. It was one of the most remarkable and comprehensive decorative programs of any American church of its day. He worked on St. Paul’s from 1899 till 1913 (as a life commitment) when he seems to have had a personal falling out with the Paulists and was fired. (There must have been a reconciliation, for he lived and died next to a Paulist retreat center) 3) Regrettably, much of Harris’s work was destroyed when the interior was repainted in the 1950’s – the most recent restoration was able to restore some of the individual paintings (like the grand crucifixion high in the rear of the church, the “Angel of the Sun” or the paintings surrounding some of the side altars) but recovered only fragments of the rest of his decor.

(Above) In the rear of the Church:more windows by John LaFarge and the immense painting of the crucifixion by Harris.

(Above) From a memorial in the south vestibule painted by Harris.

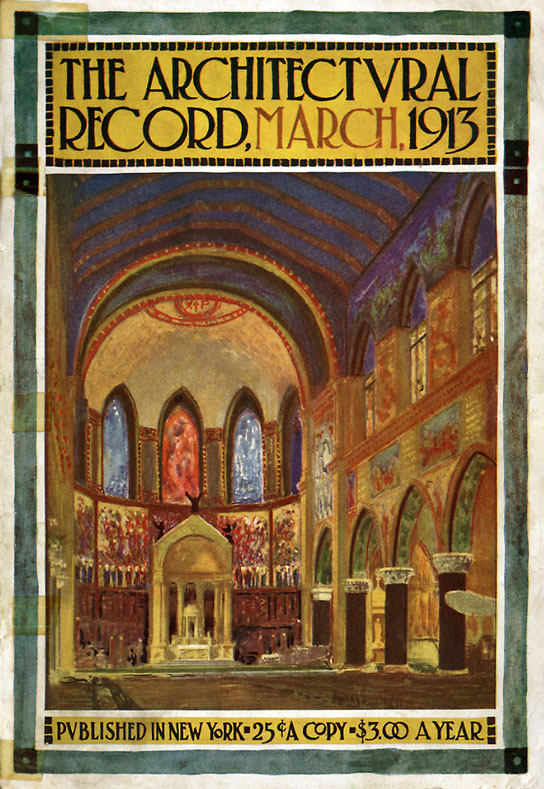

(Above) A contemporary (1913) magazine cover showing St.Paul’s interior (or a vision of the complete interior) with Harris’s murals and stencils. See notes 1 and 3.

Third, Stanford White, the high priest of Beaux-Arts style in New York, designed the monumental high altar and the two side altars. The high altar, described as “Byzantine,” includes rare and precious materials: onyx, porphyry, alabaster and Numidian marble.

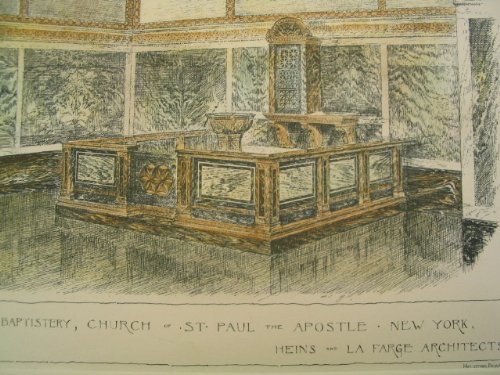

But many others contributed as well. Bertram Goodhue, the architect designer of St. Thomas Fifth Avenue, St. Vincent Ferrer etc., laid out the elaborate floor in 1920. The firm of Heins & Lafarge (Christopher Grant LaFarge was the son of Robert Lafarge and the architect of St John the Divine) created the baptistery (regrettably relocated and partially reconstructed after the Council). Then there is the painting of the martyrdom of St Paul by the American impressionist Robert Reid.

(Above) The original design of the baptistery by Heins & LaFarge in 1890; (below) As relocated and reassembled in a “post-conciliar reform.”

Although Augustus St. Gaudens himself did not contribute a work of his own hand, a number of his leading pupils did. Their statues and decoration, in their individuality and exceptional quality, set the tone of the church. Frederick MacMonnies sculpted the angels of the baldachin. Philip Martigny (or Martiny) created the grand sanctuary lamp (which, by the way, like several older New York churches, features the correct white glass). Bela Pratt’s Madonna of the Annunciation, intended to evoke the form of a lily, is especially impressive.

(Above) Reid’s martyrdom of St Paul; (Below) the sanctuary lamp(Martiny).

(Above and Below) The side altar of Mary – Stanford White, designer.

(Above) Part of the marble floor by Bertram Goodhue: “in all things extremely God-fearing”(Acts xvii. 22) – astute flattery of America.

Now the artists of St. Paul’s were admittedly men (and one woman, Cecile Wentworth) 4) who enjoyed in their day official commissions for society portraits, monuments and public buildings – not the “avant- garde.” But doesn’t this faithfully reflect American taste at the time? It is an amazing achievement – an order established to evangelize the Americans attempts to demonstrate what the religious art of these Americans – imitating European models – could achieve!

I don’t think anyone has ever been enthusiastic about the squat, rough stone exterior of St. Paul’s. The carved portals with their statues are the only obvious remnant of the original vision of a Gothic cathedral. Inside is another story. The church surprises with its vastness (it is the second largest Catholic church in Manhattan after St. Patrick’s Cathedral). The limited number of natural light sources – stained glass windows high in the clerestory and the upper reaches of the facade and apse – normally leave the church enshrouded in a mystic darkness. It is alleged that the massive, high walls not only create a mysterious, spiritual ambiance, but have a practical objective as well: they shut out the noise of the surrounding city.

(Abvoe) The altar of St. Agnes. (Below) The altar of the Annunciation.

The windows and chapels strike just the right decorative note. The series of individualized, marble side altars on either side of the nave, combined with massive walls, have reminded more than one observer of a Florentine basilica. We note the pulpit situated in the middle of the nave (so all could hear the preacher in a pre-electric age) and the reversible pews enabling the congregation to face either the preacher or the celebration of the Mass in the sanctuary.

To my taste, St Paul’s is a far more successful application of the same architectural and liturgical principles that had informed the building of St. Francis Xavier church, finished just a few years before. Indeed, it anticipates the grand Beaux-Arts spaces of the immediately following decades. But like the buildings in that style, St Paul’s seems to me to have a distinct flavor of the secular. Does it not vaguely resemble the immense hall of Grand Central Station – extending to the depiction on the ceiling of stars and constellations? (In St. Paul’s case, those of the midnight sky of January 25, 1885, the date of the dedication of the church)

But now we come to the present age. Regrettably, the chancel or sanctuary has been devastated: in 1992 a new altar was placed forward in the nave surrounded by a jumble of wooden ramps and objects (including parts of the old communion rail). The “old altar…will still be visible. …but will be de-emphasized”and reduced to an “apparent reredos” or “decorative wall.” All this was done at a cost of $1.5 million. It is a situation familiar to us from St. Francis Xavier and a host of lesser churches. The reasoning behind such travesties is not just ideological – really, is there a need for a huge sanctuary for the handful of ministers today or for an immense nave for for the diminished congregations? 5)

- Given its historical prominence, the structure and decoration of the church of St. Paul the Apostle has enjoyed much more than the usual level of attention paid to New York Catholic churches – which also results in discrepancies and erroneous attributions even in the earliest accounts. The most complete and reliable guide is Malloy, The Church of St Paul the Apostle in New York, supra, Part I note 5(1950?). Dorr, Charles H., A Study in Church Decoration: the Paulist Fathers Church in New York City & Notes on the Work of W. L. Harris, Architectural Record vol XXXIII 187-203 (March 1913) is a detailed, enthusiastic contemporary account of the decoration of the interior as it was created. Kent Becker at notmydayjobphotography.com gives us beautiful photographs with captions partially taken from official descriptions that used to be displayed in the church. Finally, the Landmard Designation of the New York Landmarks Preservation Commission, supra, Part I note 6 ( June 25, 2013) contains a wealth of curious factoids and anecdotes not encountered elsewhere.

- In the Staten Island Museum

- “William Laurel Harris” – Wikipedia

- “Cecile Wentworth” Wikipedia. Her painting of the crucifixion in the altar of St Catherine of Genoa has disappeared – replaced by a hideous “Resurrected Christ.”

- Gray, Christopher, Streetscapes: St Paul the Apostle; Renewal and Change, Esthetic and Liturgical, The New York Times (December 20, 1992) (the gullible reporter acts as a scribe of the Paulists)

Related Articles

No user responded in this post