St. John the Evangelist, 348 East 55th Street

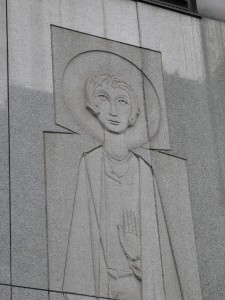

On First Avenue between East 55th and 56th Streets stands an unremarkable medium-rise office building – perhaps a bit out of place in a mainly residential area. The surroundings may appear nondescript to the uninitiated, but, a block or so to the east, is Sutton Place – a very upscale address indeed. This dark-gray building is the “Terence Cardinal Cooke Building” – “ten-eleven,” the headquarters of the Archdiocese of New York. And if we look more closely, the side of this building fronting on East 55th Street features stone facing more elaborate than that on the ground floor of the rest of the structure. It features a relief of a droopy St. John, in a style like that of the early stained glass of the cathedral of Augsburg, and some bizarre nonrepresentational patterns of lines like the strange etched panels inserted in deep space probes to convey to aliens information about humanity. ( I suspect that these on the Catholic Center rather are intended to illustrate the vision of the New Jerusalem.) Further along on East 55th Street is an awning, under which a set of institutional glass doors lead to the parish church of St. John the Evangelist.

The Second Vatican Council, its antecedents and its aftermath offer numerous intriguing parallels with developments in the secular world. Like “civil society,” the Church has experienced a “managerial revolution” (James Burnham) in which faceless bureaucrats and their allied “experts” have liberated themselves both from the control of their nominal superiors and any accountability to those they administer. Witness the role of the USCCB or of the “Catholic” universities over the years. It is no accident, then, that the most impressive Catholic project of the entire post–Conciliar era in Manhattan should be not a church, school or hospital but a new office building to house the managers of the Archdiocese. At “ten –eleven” the church bureaucrats demonstrated their power (at least to the Catholic population) – abandoning the Renaissance splendor of the Villard houses, demolishing a traditional Catholic parish church and creating one more expressionless product of modernity.

Now this structure is not just an office building – it is also a church. The property on which 1011 was built was the old parish of St. John the Evangelist, an impressive neo-gothic edifice built in 1886. The recent exhibit at the Museum of the City of New York on “Catholics” featured a wooden model of this church lovingly assembled by a parishioner. (The exhibit did not mention that the church had been demolished).

But the parish of St. John the Evangelist was reincorporated within the new skyscraper and reopened in 1973. The first pastor of the new church was Msgr. George Kelly – yes, the author of the “Battle for the American Catholic Church,” a founding text of “conservative Catholicism.” Monsignor, who found all problems to be reducible to a question of obedience, obviously was not troubled by inflicting things like the new St. John the Evangelist on the Catholic population – as long as proper authority had ordered it.

(5 years ago an oil painting of Archbishop Hughes used to adorn the vestibule to the Church -the identifying plaque had been ripped away.)

In a sense, St. John the Evangelist is the logical end result of the Conciliar philosophy, in which the Church accepts a role as one group among many attempting to make herself heard in the “public square” of the secular city. Until funding petered out, a handful of new churches continued to be built or rebuilt through the early 1970’s, architecturally of incredible ineptitude: the Church of the Epiphany, the Church of the Nativity, the NYU Catholic Center. But however misguided, these buildings still stood apart as churches. St. John’s, however, disappears entirely and is absorbed into the diocesan office building. The Catholic Church in this neighborhood is no longer represented by a neo-Gothic “house of God” but by an anonymous, secular structure, indistinguishable from dozens of others built in the same era. But a comparison with the leading secular competition of that time – like the late unlamented World Trade Center – reveals the discrepancy in power and resources between the Archdiocese and the forces of civil society with which it was so eagerly trying to make arrangements. The recent Opus Dei Center on East 34th street has continued and even reinforced the trend to anonymity; the model this time being not an office, but an apartment building. But keep in mind that St. John the Evangelist, in contrast to the sanctuaries of that building, is not a private chapel but is intended to be a parish church for its neighborhood.

Inside, this church resembles nothing so much as a lobby of some expensive apartment building – or perhaps a restaurant. Indeed, St. John’s IS a lobby – one can walk from East 55 th Street through the church to the main entrance to the office tower. The space is a low ceilinged rectangular box, painted in stark white and black. An altar is in the center, sorrounded by pews on three sides. In the four corners of the rectangle are an organ, the tabernacle, the baptismal font and a dark “Saints’ room” (originally a “Lady Chapel”), respectively. At mass, the congregation on the left side of this church sits with its back to the tabernacle. The altar, the tabernacle and the font are emphasized by tubes and rectangular forms hanging down from the ceiling.

The original decoration, largely intact, is more timid than the architecture. There are washed out wall hangings and “modernistic” Stations of the Cross. But the crown of the original decorative scheme (fortunately recently replaced) was a wooden relief behind the altar showing a stick –figure Christ with outstretched arms and a scooped-out, faceless head.

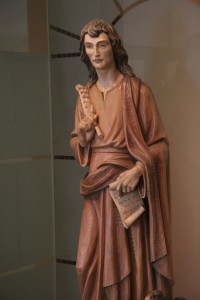

In 1973, St John represented the extreme limit – at least in New York – of the Conciliar “hermeneutic of rupture.” Yet, as the years went on, forces of resistance gathered among both the laity and the clergy. The statue of Mary, presumably part of the original art work and a fine work in the German style, was a point of departure. A traditional statue of the Virgin is also a feature of many modern German churches – it seems difficult to conceive of Our Lady in the grotesque forms of modernity. Gradually she was joined by a whole series of statues and devotions multiplied in this confined space: St Francis, Divine Mercy Sunday etc. A succession of pastors added traditional windows and icons (more on this below). Finally, two years ago, a more through restoration added various works of figurative art. Most notably it replaced the awful faceless relief of Christ with a traditional crucifix. Even though much of this artwork is of indifferent quality, the tendency is clear: a restoration of Christian culture in this most un-Catholic of environments has taken place.

The new crucifix is superimposed on the old modernistic relief.

Consider this development: the original (I assume)furnishings included this tabernacle – modeled vaguely on the old church of St. John which had been razed.

Around 2000, new windows in a non-modern style were introduced. They include this illustration of the old church.

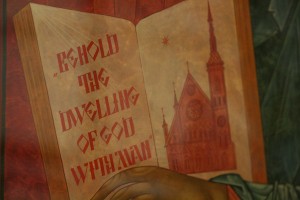

Perhaps at that time these fine icons were also acquired. They originally flanked the former image of “Christ” behind the altar.

Here again, St. John holds a picture of the old St. John’s!

What could more clearly illustrate the bankruptcy of the modernism of St. John’s than the fact that in each case when that church – or the Church -needed to be illustrated, the artist had to turn back to the image of the original edifice! Now, all the new sculptures and icons in the world cannot cure the fundamental defects of the architecture of the (modern) St. John’s. But it gives cause for comfort that, like the vegetation returning after a volcanic eruption, a Catholic sensibility has crept back and has remeined alive through the decades in the very heart of modernity.

Related Articles

1 user responded in this post