Sacred Then and Sacred Now: the Return of the Old Latin Mass

Thomas E. Woods, Jr.

Roman Catholic Books,(Fort Collins, CO 2008) (Reprint 2013)

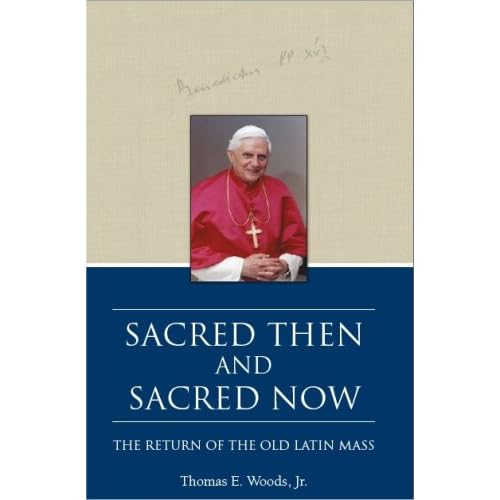

A kindly, smiling Benedict XVI appears on the cover of this 2008 work. Benedict’s signature also appears prominently. Sacred Then and Sacred Now, reissued without apparent change, was one of the first reactions to Summorum Pontificum (“SP”). Do we need to add that much has changed since then – even in the last month? Yet Sacred Then and Sacred Now retains its utility as a primer on the Latin Mass for those unacquainted with Catholic Tradition.

The first chapter lays the foundation for understanding SP. It is evident that the addressee of this book is not just any reader – whether a Catholic “man in the street,” an unbeliever or a progressive – but specifically a representative of the “conservative Catholic” milieu whose overriding concern is conformity to Authority. This introductory chapter reassures this Catholic bien-pensant, fearful of transgressing the rules set down by Authority, that it is safe to have concerns about the new liturgy and to frequent the Traditional Catholic Mass. It then, however, brings forth more substantive arguments for the Traditional Mass, as formulated by Michael Davies, Klaus Gamber, and especially Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger. By linking the legislative rules of SP to these prior analyses – particularly those of Cardinal Ratzinger – the author of course supplies a key or “hermeneutic” for the proper interpretation of SP. Not that all these prior positions are wholly coherent upon closer examination. For example, then-Cardinal Ratzinger “did not regret that the reform ever took place” (p.4) yet raised what appear to be fundamental objections to it (“excessive creativity” and “desacralization” as to which the text of the new missal “was not altogether blameless” (p.9)). But then Sacred Then and Sacred Now is not intended to provide a scholarly critique but to give the basics necessary to understand the origin of SP.

The next chapter briefly considers the rules of SP. We can wholly concur with the author’s conclusion that they are revolutionary – a fact perhaps not understood by their author himself. Here of course, Sacred Then and Sacred Now would have benefitted from a revision to take into account the subsequent instruction Universae Ecclesiae. This instruction provides sounder support and further clarification for the interpretations of SP the author makes in this book. Moreover, we do find it anomalous that then-Bishop William Lori of Bridgeport is cited as a proponent of SP – he certainly was not in actual practice. At best, he didn’t “get in the way” of certain local initiatives.

Chapter 3 is far longer and is a straightforward, non-technical exposition of the “Latin Mass” for those having very little knowledge of it. The author takes the Missa Cantata as the basic model of the Extraordinary Form. Low Mass is only very briefly sketched out, even if this form was and is exceedingly common. In this area too, post-2008 developments have overtaken the situation described in this book. For example, Thomas Woods mentions (but does not describe) the Solemn High Mass. Yet in not a few places this form of the Mass has become almost routine for special feasts and occasions (and at least one parish it is the regular Sunday liturgy!). And even the Solemn Pontifical liturgy, almost unheard of even before the Council, is celebrated more and more frequently! I would suggest for a subsequent revision of this book a more detailed presentation of all three commonly encountered forms of the Mass.

Chapter 4 details ”Important Features “ of the Extraordinary Form. In keeping with the non-technical nature of this work, these are externals: communion received on the tongue – while kneeling, absence of Eucharistic ministers and exclusively male altar servers. Chapter 5, dealing with “Common Misconceptions,” in effect resumes the thread of argumentation of the first chapter and seeks to make the intellectual case for the Traditional Mass against the usual objections (“celebrating with the back to the people” etc.). Sacred Then and Sacred Now concludes with several source documents – including the text of SP.

In summary, Thomas Woods has written a short, solid work whose judgments about the nature and scope of SP were validated by subsequent practice and official interpretation. As we have indicated, however, these – mostly favorable – developments have outstripped in a number of respects the situation described in this book, which accordingly would benefit from updating.

But then there are the developments of the last several weeks. One wonders what the author will say now that there is a new pope whose liturgical ideas seem to be the exact opposite of those set forth in Sacred Then and Sacred Now. The reign of Pope Benedict, evoked by his smiling portrait on the cover of this book, already seems like a distant, melancholy memory. Will support for Catholic Tradition collapse now that it is for the moment impossible to claim the direct support of the Pope? We do not think so. For, fortunately, the course of liturgical renewal has a much stronger foundation – outlined succinctly in this book – than the uncertain and shifting winds of official ecclesiastical favor.

Related Articles

No user responded in this post