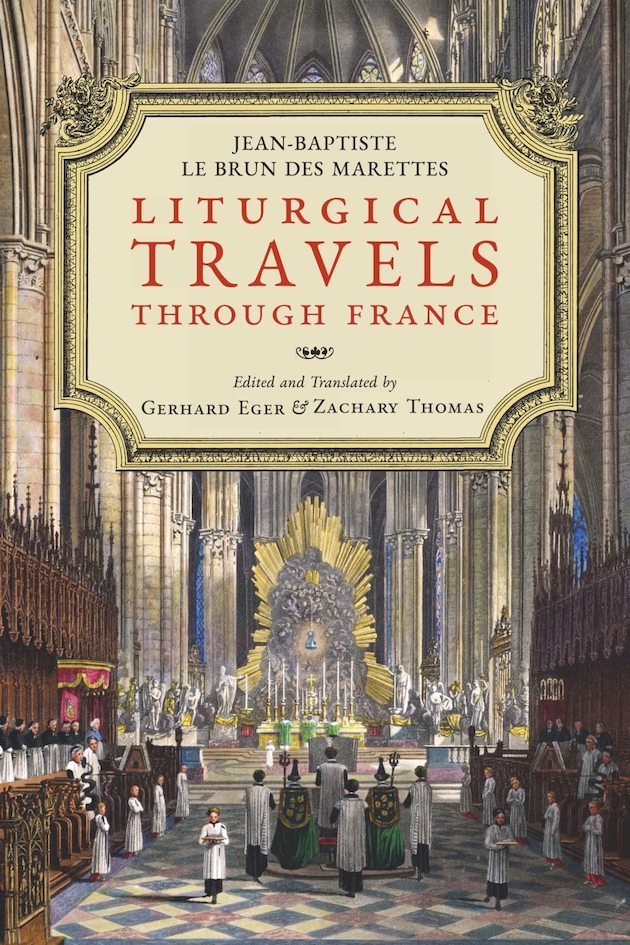

Jean-Baptiste Le Brun des Marettes

Edited and translated by Gerhard Eger and Zachary Thomas

Foreword by Fr. Claude Barthe

396 pages

(Os Justi Press, Lincoln NE 2025)

Os Justi Press offers us a new edition and translation of the Liturgical Travels of Jean-Baptists Le Brun des Marettes. It’s a unique journey through the Catholic Church of France as it existed in 1718. Thus, it describes the liturgical situation of France after the impact of the Protestant Reformation, of the Counter Reformation, of the Gallican and Jansenist controversies but before the simplifications made in the Church as reconstituted in the wake of the French Revolution. This perspective is unique. I had previously written about the account of Wilhelm Wackenroder, a later German writer, who also described a liturgical visit at the end of the 18th century to Bamberg, a Catholic diocese where the ancient rite still flourished. But that writer was a Protestant, completely unfamiliar with Catholic culture and the rituals the witnessed. Le Brun des Marettes, however, writes not only as a convinced Catholic but also as a representative Jansenist of that era.

Now the author unfolds an amazing picture of the practices of the French Catholic Church in those days. For La Brun des Marettes liturgy is not just the celebration of mass, but also blessings, chanting of the divine offices and above all processions. Above all the ceremonies of Holy Week receive detailed treatment. Throughout Le Brun des Marettes provides many curious details. He claims, for example, that in one monastery in Poitiers, nuns formerly served as acolytes vested in surplice and maniple. And we repeatedly read in Liturgical Travels of the employment of the rood screen, where it still existed, for the chanting of the readings of the Mass. Le Brun des Marettes frequently enriches his discussion of the various liturgical uses he encounters by reference to the practices in Rome, Milan (the Ambrosian rite) and the Byzantine liturgy

Furthermore, the performance of these French liturgical rites was inextricably intertwined with the secular culture – ecclesiastical ceremonies might be the occasion of the distribution of gifts or remuneration, the acknowledgement of feudal obligations or the administration of charity. Truly this is a perfect picture of integralism!

The commenters in the New Liturgical Movement of some years past, who scrutinized and critiqued every detail of the ceremonies described or photographed on the pages of that blog, would find this book informative. Indeed, Shawn Tribe, the founding editor of that website, has contributed a very fine essay to this volume. Yet these amateur critics will find within nothing corresponding to their vision of a uniform, fixed, immutable set of rubrics governing everything.

For the liturgical diversity described by Le Brun des Marettes is the product not just of the conflicts of the two centuries preceding his own era but, in some respects, dates back to late Roman times. It is all the result of organic development, not of dictates from centralized authority. More recent influences on the national and international level had been incorporated into the existing local tradition.

Nor will the Vatican and the Catholic Church establishment find in this book support for their current certitudes. For, contrary to what Pope Francis and his acolytes claimed, after the Council of Trent Pius V did not repudiate all prior uses and establish liturgical uniformity throughout the Western Catholic Church. Total liturgical uniformity had never been implemented even in the Western Church. This book demonstrates that , contrary to Cardinal Roche’s recent assertions, while diversity existed and development was possible, all was regulated by the exact performance of historic tradition – there was no formless flux of change.

Of course, this situation described in Liturgical Travels depended on the existence of many subordinate institutions within the Catholic Church: monasteries, collegiate churches and above all the cathedral chapters of canons, all richly chronicled in this book. The canons of the cathedrals were the guardians of the local liturgies. This liturgical diversity disappeared largely because the institutions described in this book also has been swept away or radically transformed after 1789. Later, such cathedral chapters seemed completely alien to the Catholic clergy themselves:

We (in the United States in 1930 – SC) have attained to our full ecclesiastical stature. Prelates, robed for ceremony, should adorn our more solemn religious functions. The Roman purple is now necessary to give character and color to our Pontifical occasions. The stately cathedral demands the purple stall. We have not and let it be devoutly hoped that we never will have, cathedral canons, but we have and we should have a growing number of monsignori – men who have led distinction to religion in their own parishes and who are intellectually as well as ecclesiastically an ornament to the church. 1)

Now Le Brun des Marettes is a Jansenist. Our author writes particularly complimentary descriptions of certain Jansenist monasteries. This tendency also is evident in his consistent advocacy of simplicity and of returning to supposedly ancient practices. So, he commends those churches where the altar remains bare prior to the Mass and refers to the famous discussion of the purpose of candles in Catholic services – are they symbolic or do they merely provide illumination? Thus, our author touches on topics that many years later were taken up by a more extreme generation of Jansenists and then by the liturgical movement in the 20th century. Indeed, they reflect a radical change in the spiritual outlook of Westen Man.

However, Le Brun des Marettes is in no way an early representative of the culture of Vatican II. In true Jansenist manner, he repeatedly advocates, not the relaxation of norms, but a return to earlier, more severe forms of devotion and penance. Above all throughout the book our author constantly returns to the exact performance of rite. The variety within the French church may have been great, but everything in every individual church was precisely governed by law and custom, not by the exercise of flexibility or creativity.

Now our author is by no means perfect. His selection of churches is unsystematic, with some (notably Rouen) receiving far more attention than others. There’s a fair degree of repetition. At times it is unclear whether a particular ritual described by Le Brun des Marettes was actually being practiced in the author’s day – or whether it was something he had found in an early manuscript. The author helpfully describes now and then architecture, inscriptions and monuments, often Roman, but in not in any methodical manner. And obviously some of his conclusions have been overtaken by liturgical scholarship in the last 300 years.

Nevertheless, I found this book a clear and interesting read – also thanks to the translator. This edition is supplied with notes that are a great aid both to one familiar with the liturgy and to the reader completely unfamiliar with the topic. Furthermore, there are helpful introductions and essays included in this edition. Some valuable illustrations dating back to the 19th and 18th centuries complete the presentation.

I see Liturgical Travels as being of greatest interest to the Catholic traditionalist who has long personal experience of participating, as celebrant, minister or member of the congregation, in the celebration of the traditional rite – especially in the solemn Mass and vespers. In Liturgical Travels he will find a multitude of insights into the practices with which the has become familiar. Indeed, the presentation of the many alternatives found in this book will only increase his appreciation of his rite. Those who have the good fortune to be able to participate in Sarum use or Dominican liturgies will be especially grateful to this book– for these alternative liturgical uses have survived to the present day and indeed have points of resemblance to the liturgies of the French cathedrals described in Liturgical Travels.

- Duggan, Thomas S., The Catholic Church in Connecticut, at 203 (The States History Company, New York City, 1930). The author was vicar general of the Hartford, CT, archdiocese.