Gli Imperdonabili

By Cristina Campo

Adelphi Edizione, Milan, 1987.

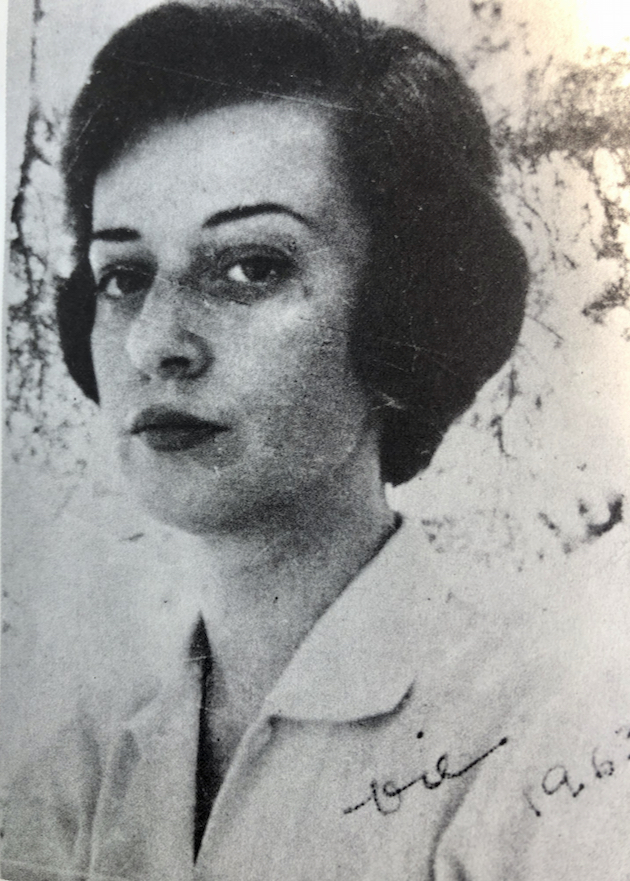

Cristina Campo (real name: Vittoria Guerrini, 1923-1977) is among those who first reacted to the revolution in the Church of the 1960s. A noted author in her own country, she wrote of the crisis of the modern world in all its forms. But she did much more than merely play the role of a cultural critic: galvanized by the liturgical changes of the Council, she became an early activist in the effort to preserve the Traditional liturgy. She was one of the cofounders of Una Voce Italia. She organized a petition from noted intellectuals in 1966 for the preservation of the Latin mass – in some respects her petition had more notable names than the later, much better-known “Agatha Christie” petition in Britain. Then, in 1969 she was one of the main editors of the so-called “Ottaviani Intervention” against the Novus Ordo mass. Later, after the Latin Church had abandoned its liturgy, she turned to the Eastern rites which she encountered at the Russicum institute in Rome. For reasons we will explore later Campo fell into undeserved obscurity – among Catholics, that is. For example, Leo Darroch’s Una Voce: A History of the Foederatio Internationalis Una Voce does not even mention the role of Campo or Una Voce Italia in the “Ottaviani Intervention” – one of the two or three most important concrete actions that Una Voce ever undertook in the forty- year period covered by this history! 1)

The Unforgivable, a collection of essays, is Campo’s representative prose work. In it, she covers a broad range of subjects: poetry from all ages, literary criticism, fables and folklore, spiritual writing and liturgy both East and West. Her style lies somewhere between that of an essay and a prose poem. Indeed, the use of repeated themes and poetic symbols throughout this volume provides a certain unity to this book: oriental carpets (including those that fly), flowers, destiny, the need for “attentiveness,” the liturgy. The depth and range of her knowledge is astonishing. To mention but a few of her sources, in addition to Italian icons like Dante, Leopardi, Manzoni and Lampedusa she cites literature in English (Donne, Pound, Emily Dickinson, William Carlos Williams but also Arthur Machen 2)), French (Proust, Simone Weil ), German (Benn, Hölderlin and Hofmannsthal) Spanish (Borges) and Russian (Chekhov, Pasternak and Pushkin). But she also draws on folk and fairy tales, the Church fathers, the lives of the saints, the spiritual and liturgical tradition of the East but also that of the Catholic Counter-Reformation.

I will discuss here those sections of The Unforgivable touching most directly on Catholic and religious matters such as theology, liturgy and “Christian culture.” Please forgive me in advance for any mistakes. Campo’s erudite Italian is as challenging as any poetic text must be, and Italian is not my best foreign language! Indeed, it has often taken me multiple readings to “decipher” some passages.

The Unforgivable, the essay from which the collection takes its name, deals with poets and poetry’s necessary search for perfection of form. The poets’ sensitivity to beauty marks them as outsiders, even outcasts from the current world. But it also leads to a distinct spiritual culture, an attitude to life. She explores this topic through a series of symbols and images, starting with the description of a Chinese man, who, while standing in a queue waiting for his execution after the Boxer rebellion of 1900, calmly concentrated on reading a book. Or Hugo van der Goes’ portrait of the donor of the Portinari altarpiece whose aristocratic image adorns the cover of this edition of The Unforgivable. (As a Florentine, Campo would be most familiar with this work!). Even though this essay is not overtly religious, do I need to point out its obvious conflict with the Roman Catholic Church since the Council with its endlessly repeated contempt for beauty and for the “esthetes” (the ultimate insult!) who care for “museums.” A contempt recently forcefully reiterated by Pope Francis, 3) who, moreover, also disdains the search for perfection in the moral and spiritual life as well.

Il Flauto e il Tapeto (The Flute and the Carpet), for me the centerpiece of this book, deals with the providence of God as manifested in the life of each person, starting with an image from Psalm 57(58) of a snake responding (or not) to the charmer’s musical call. It is a melody meant individually for each of us. We can call it destiny, a calling or in Christian terms, a vocation. It is a summons that is often drowned out by the noise of today’s world in which the sense of an individual destiny, like that of the meaning of symbols, seems to have been lost.

For religion is nothing but sanctified destiny, and the universal massacre of the symbol, the unatonable crucifixion of beauty are, as I have said, the massacre and crucifixion of destiny.

Yet once this destiny is perceived, we discover an interconnectedness in our lives. There is meaning to our existence but in this world we can never fully unravel it. It is like discerning the pattern of an oriental carpet by looking at its reverse. Yet Campo trusts that, amid the universal horrors and ugliness of this age, there will always be those, who may be found in the most unlikely situations, who will hear and respond to this call.

Reading these profound yet mysterious passages, I was reminded of Martin Mosebach’s account of his own spiritual journey:

I ought to have accepted, long ago, that I live in a chaos, that there is nothing in me that can say “I” apart form some neural reflex, and that every sense impression of this nonexistent “I” rests only on illusion and deception: nevertheless, when I hear the blackbird’s evening song…and when I hear the distant clang of the church bell… I hear these things as a message – undecipherable maybe – that is meant for me. People say, and I should have grasped it long ago, that the objects surrounding me have not the slightest significance, that there is nothing in them and that what I see in them is what I read into them (and who after all, am I?) Yes, I hear all of this, but I do not believe it. (My bolding – SC) 4)

Further, Campo links destiny (now the interlinked destiny of all men, indeed, of the whole universe) to the liturgy – which sums up and describes the entire “history of salvation” through the “supreme intellectual beauty of the gesture.” She writes unforgettably of the ceremony of the vesting of a Byzantine bishop involving a dense interplay of gestures, music, incensation, vestments and liturgical colors, in which the bishop advances symbolically from a mere individual to one having the full powers of the Unique Model. The vesting proceeds from the black penitential monastic garment to “the scarlet of the monarch and the martyr, the stole of the sanctifier, … to the crown of the celestial king.” Anyone who saw last year Archbishop Salvatore Cordileone perform the Western equivalent of this rite at a Solemn Pontifical Mass in San Francisco will never forget the experience. (pp. 132-34).

Her final, purely “religious” essay of this book, Sensi Supernaturali (Supernatural Senses), evidences her deep understanding of liturgy. Here she writes of the concreteness, physicality and corporality of the Catholic religion. Christ of course talked of “eating my Flesh and drinking my Blood.” Such are also the witnesses of those ancient times – St. Ignatius of Antioch for example describes how, after eating the body of Christ he will in turn become himself bread – a sacrifice in the arena in Rome to be devoured by wild animals. And this tradition continues up to the physical gestures, the veneration of relics and the processions so much a part of the Christian culture of the Mediterranean countries even today. Above all, it is the (traditional) liturgy which employs all the senses. In it:

“All the five senses are launched out into the deep, outside of the body, outside of the “demoniac space” of the world, towards a state of acute vigilance, skillfully called up and perpetuated, which is already the beginning of their transformation.” (p 246)

We would think that such an author, a woman too, would have remained a cherished figure in Catholic circles, a showpiece for the Church. But that was not to be. Some of the reasons are objective. Her style, while evocative and beautiful, is not exactly easy reading. Almost none of her work has been translated (yet) into English. Poets, especially modern poets, necessarily are restricted to a limited audience in their own language.

But there are also ideological reasons for the lack of interest in Cristina Campo. As for the Church establishment, it should be clear from the above that Campo’s thoughts on beauty, perfection of form and the liturgy are the exact opposite of the principles governing the current regime in the Church. The reservations of the traditionalists are somewhat less easy to understand.5) It seems that Campo’s wide interest in such things as the thought of Simone Weil, the Western hermetic tradition and eastern religions is distressing to the more “rigid” people on the right – some in the sedevacantist realm. For them, the basic reference materials of a Catholic are limited to the papal magisterium between 1846 and 1958, the Catechism of the Council of Trent and neo-scholastic theology. For example, Campo’s audacious and creative juxtaposition of Catholic devotions to Hindu theological concepts is suspect to them. Moreover, there is a photograph of Campo sitting in a yoga pose that is calculated to drive such people into incoherent rage. Finally, Cristina Campo may have been naughty in some aspects of her private life. But let me conclude these considerations by quoting an appreciative letter of Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre from 1986:

Cristina Campo! What a memory during that awful Council! How much encouragement we received from her to carry on the good fight! She saw the invasion of the enemies of the Church and of the true Rome better than we did. She was right then and still is right today: the enemies are everywhere the Church and especially in Rome. 6)

Tragically, Cristina Campo, who never seems to have enjoyed good health, died in 1977. She was of that first generation of Catholic apologists – almost all from the ranks of the laity – who clearly saw the looming disaster and courageously strove against it. Among them, she was also of the few that grounded her opposition to the Conciliar changes by reference to an objective context: the entire Catholic tradition, East and West, as well as philosophy and literature, both Catholic and non-Catholic. This distinguishes her from those who, on the one hand, reacted only emotionally, or, on the other, relied only on the post-1846 Catholic magisterium. I would hope the work of Cristina Campo becomes an important reference for a traditionalist movement still working to develop its own self-understanding.

The website www.CristinaCampo.it contains almost everything written about her. Moreover, the life and writing of Cristina Campo may soon be much more accessible to the English-speaking reader. There is an English translation online of the essay “The Unforgivable,” with valuable commentary. 7) If I am understanding their announcement correctly, Penguin/Random House will be publishing early next year a translation of the complete The Unforgivable plus additional materials. 8) Finally, Martin Mosebach informs me that a book by Joseph Shaw, “The Intellectuals and the Old Rite,” will be forthcoming shortly in which Cristina Campo will feature prominently.

- 1964- 2003. Darroch, at 31. For a brief biography of Campo along with a bibliography see Chiron, Yves, Histoire des Traditionalistes at 498-499 (Tallandier, Paris 2022)

- The cite to one of Machen’s stories on p.127, 259 is inexact in this book. The full cite (actually, Campo’s quotation is a paraphrase) is “The White People” at 111 in Machen, Arthur, Tales of Horror and the Supernatural (Tartarus Press, Carlton-on-Coverdale, Lyburn 2006)

- E.g., Pope Francis, Letter to the Priests of the Diocese of Rome (8/5/2023) “And, again, by vainglory and narcissism, by doctrinal intransigence and liturgical aestheticism, forms and ways in which worldliness “hides behind the appearance of piety and even love for the Church”, but in reality “consists in seeking not the Lord’s glory but human glory and personal well-being.”

- “Eternal Stone Age” in Mosebach, Martin, The Heresy of Formlessness: The Roman Liturgy and its Enemy (trans. Graham Harrison) at 18-19 (Ignatius Press, San Francisco, 2006; first German edition, 2002)

- Porfiri, Aurelio, “Cristina Campo and the Monsters of Traditionalism,” OnePeterFive (4/28/2023) Aurelio Porfiri has the merit of bringing Cristina Campo to the attention of the English- speaking public upon the hundredth anniversary of her birth.

- Letter of Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre of 8/5/1986, at CristinaCampo.it (my translation – SC)

- The Unforgiveables (sic) by Cristina Campo, a translation with a commentary, Andrea di Serego Alighieri and Nicola Masciandaro. From Glossator 11; Cristina Campo, (6/11/2021) (This publication also includes translations of other works by Campo)

- The Unforgivable, by Cristina Campo, Introduction by Kathryn Davis, translated by Alex Andriess (anticipated issue date 2/06/2024)

Related Articles

No user responded in this post