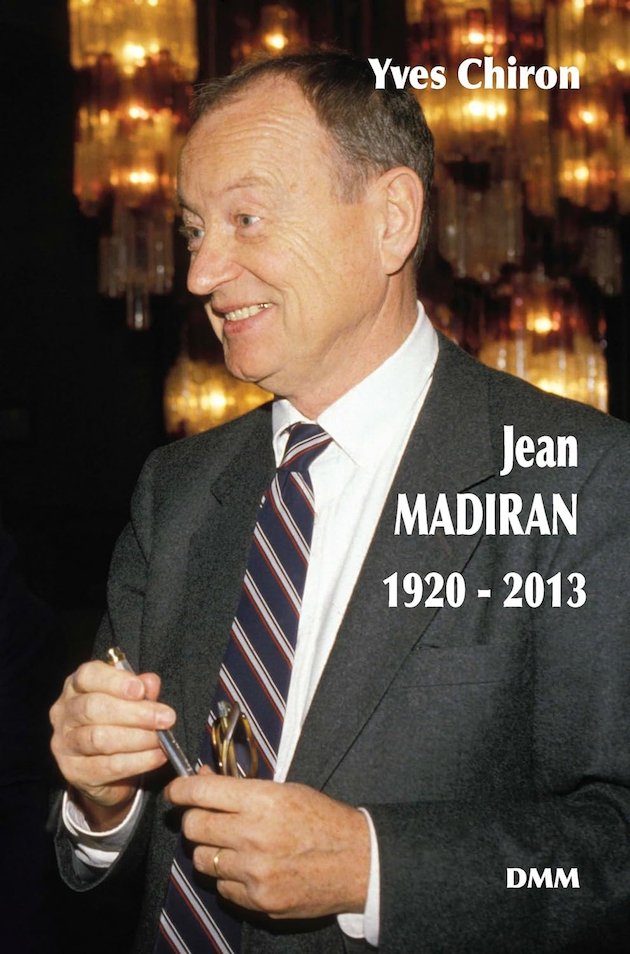

Jean Madiran 1920-2013

By Yves Chiron

(DMM, Poitiers, 2023)

Continuing our review of the recent flood of major publications on the sources of the Traditionalist movement, we come to Yves Chiron’s new biography of the towering figure of Jean Madiran (real name Jean Arfel). In many respects he was “Mr. Traditionalism” in France (next to Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre of course!) I find Chiron’s magisterial biography even more successful than his previous history of Catholic Traditionalism.1) Both books cover in encyclopedic detail a period of many decades starting from well before the Second Vatican Council and leading up to the present. Yet by its nature Chiron’s biography has greater unity and focus, for it enjoys a central point of reference: Jean Madiran. In the course of his long life, he interacted with almost everyone in the Traditionalist French “scene” – and beyond. Moreover, perhaps because the narrative ends with Madiran’s death in 2013, the author is free from the need to harmonize his history and the current regime in the Vatican.

Professor Chiron tells the story lucidly, not disguising aspects of the life of Madiran that may surprise some readers. Such as his initial career as a young Vichy supporter. Or certain marital complexities that Madiran experienced in his early years. And we are told of a festive celebration of Madiran’s 75th birthday during which a girl jumped out of the cake. At this same party Madiran received a gift of two tickets to Disneyland Paris, which he previously had found enjoyable. (p.473) Well, we all have our foibles….

Madiran embodied that intransigent form of Traditionalism from which so many supporters of the Old Mass would like to distinguish themselves: counter-revolutionary, “integrist,” Maurrassian! The largely imaginary “far right” political connections of Traditionalism remain a focus of rage for the Catholic establishment of the United States, Europe, and the Vatican. (The much more concrete and systematic ties of the institutional Church – including the so-called “left” – with the Western political establishment are of course never an issue for them). In the case of Jean Madiran, however, these rightist political commitments were very real. And this was for him a source of strength, not of weakness. For defense of the Catholic religion was for him inseparable from the defense of the French nation as it was concretely lived.

Madiran, of course, was a dedicated follower of Maurras, to whom he remained faithful all his life. Indeed, after the war, some of his earliest efforts were appeals on behalf of various Vichy figures facing imprisonment or worse under the new regime. Thus, his first engagement was political. Yet, in 1946-47, Jean Arfel discovered the priory of Madiran near a school where the was teaching. (He later took his penname from this priory.) He made a retreat there, discovering the Benedictine life organized around the singing of the divine office, the meals taken in silence and the primacy of contemplation. And he had a spiritual experience in which the gospel first began to speak directly to him. Years later he would refer quietly to this moment of enlightenment. (pp. 67-68)

Madiran developed into a redoubtable journalist and organizer. In 1956 the founded his own magazine Itineraires, which published contributions from a whole galaxy of writers from the religious and political Tradition (including those of my own revered friend Thomas Molnar) Later, in 1982, Madiran cofounded a newspaper, Présent.

Madiran had and has the reputation of a militant polemicist. Yet Chiron points out that he also showed considerable talent for compromise and cooperation (for example, in his friendly dialogue with Etienne Gilson after the Council). It also may surprise the “Anglo-Saxon” reader to discover how often – at least in the earlier years – Madiran would sit down with his journalistic adversaries (generally not his clerical opponents!)to discuss their contrasting positions. These encounters often took place in a restaurant – it is France, after all! Such exchanges of views would be unthinkable in the United States today, where both the progressive establishment and the feeble “conservative” centers talk only to themselves.

By the 1950s, Madiran began to focus on deviations in the Roman Catholic Church. in 1955 he wrote the first work that won him notoriety, They Know not What They Do, a critique of the drift of the French Church towards accommodation with communism. In one sense, this concentration on anti-communism was a retreat from his initial full-blown counter-revolutionary, even reactionary, cultural criticism. A loose contemporary analogy in the United States would be the focus of National Review magazine on anti-Communism. In that connection, on the religious front, William F. Buckley spoke out against both Dorothy Day and Pope John XXIII’s encyclical, Mater et Magistra.

Of course, the French situation was entirely different from that of the United States. In France, Marxism had acquired almost a dominant position in cultural life and even among the Church intellectuals. Madiran’s book was accordingly very ill received by the clerical establishment. The French bishops took Madiran’s book as an affront. He was denounced in pastoral letters and statements. Madiran’s attempts to obtain support from the Vatican (in 1955-58!) were fruitless. Indeed in 1958 , the substitute of the Secretary of State counselled Madiran “to act within the views of the hierarchy – don’t just inform them but consult then in advance.” Chiron comments that this was equivalent to counseling blind obedience or at least the acceptance of control. (p.152) Note that all this happened before the Council and indeed mostly under Pius XII.

With the Second Vatican Council, Madiran shifted his focus once again. Uneasy at Vatican developments as early as the publication of Mater et Magistra in 1961, Madiran grew increasingly critical as the Council and its aftermath unfolded. It is generally forgotten today that, except for some independent priests, opposition to the Council, its implementation, and its “spirit” in the early years of 1964-71 was led by the laity. One can compare, in the United States, the circle of writers involved with Triumph magazine.

In 1968 Madiran resolved henceforth to attend only the old liturgy. He became a tireless defender of the traditional Mass and fought first for its preservation and later for its official recognition. He fought other deviations in the French Church, such as communion in the hand and modernist catechisms. In 1968 he summarized his convictions in his main work The Heresy of the XXth Century. Madiran’s activism and criticism of specific bishops earned him the undying enmity of the French episcopate. Who has been proved right? – I believe the facts of the French Church today speak for themselves. Consider the title of a recent book on “FrenchChurch” written by two stalwarts of the local establishment; Vers L’Implosion? 2)

After 1971, Madiran became an active supporter of Archbishop Lefebvre as he built up his seminary and order. Yet in 1988 he broke with Lefebvre over his consecrations of bishops. Later, however, it seems Madiran had to grudgingly reconsider – at least in part -his criticism of Lefebvre’s actions at that time.

By 1989 the Soviet empire was well on the way to irreversible collapse. The Western establishment, instead of recognizing with either gratitude or an apology the superior judgment of those who, like Madiran, had for so long forcefully denounced the theory and practice of communism, instead turned even more strongly against these prophets. In Madiran’s case, it was in the 1990s that he suffered the harshest attacks, both journalistic and legal. Of course, Madiran himself gave his own answer to the politics of the new world order – he became a defender of the Front National.

Is the world not strange? Towards the very end of his life, during the pontificate of Benedict, Madiran finally enjoyed a modicum of official recognition from the Church – in the wake of Summorum Pontificum. He was kindly received by Pope Benedict and at the Vatican; he was also honored at a grand festive dinner in Rome surrounded by traditionalist representatives. It was a well-deserved reward for someone who had fought for Catholicism so long in the face of official clerical disdain. Of course, such gestures would be unthinkable today under Pope Francis and his team in the Vatican – both by reason of their ideology and their utter lack of manners.

Jean Madiran died in 2013 – his requiem was in Versailles at the famous church of Notre-Dame des Armées. 3) He had been a peerless champion in France of Catholic tradition and politics. Yves Chiron’s book will offer you a thousand additional details about his life and the saga of French traditionalism. I warmly recommend you discover it for yourself!

- See my review and description: Histoire des Traditionalistes

- Hervieu-Léger, Danièle and Schlegel, Jean-Louis, Vers L’Implosion?: Entretiens sur le présent et l’avenir du catholicisme (Seuil, Paris, 2022). The authors, however, don’t seem to have any ideas to address the crisis other than continuing the regime of the last 60 years.

- See The Homily at the Funeral Mass for Jean Madiran

Related Articles

No user responded in this post