Edited by Joseph Shaw

Foreword by Martin Mosebach

(Arouca Press, Waterloo, Ontario Canada 2023)

Recent publications have enabled us to revisit, from the traditionalist perspective, the years of the Second Vatican Council and its immediate aftermath, as found in the writings of concerned contemporary observers. These records have a special attraction for us – these initial impressions often have an immediacy , frankness and freshness that disappeared later. After the early days, those struggling to preserve tradition often felt the need to make compromises or ingratiate themselves with the hierarchy. In our era when much of the clerical establishment once again has rejected all notion of compromise, it is fascinating to revisit these beginnings of the traditionalist movement.

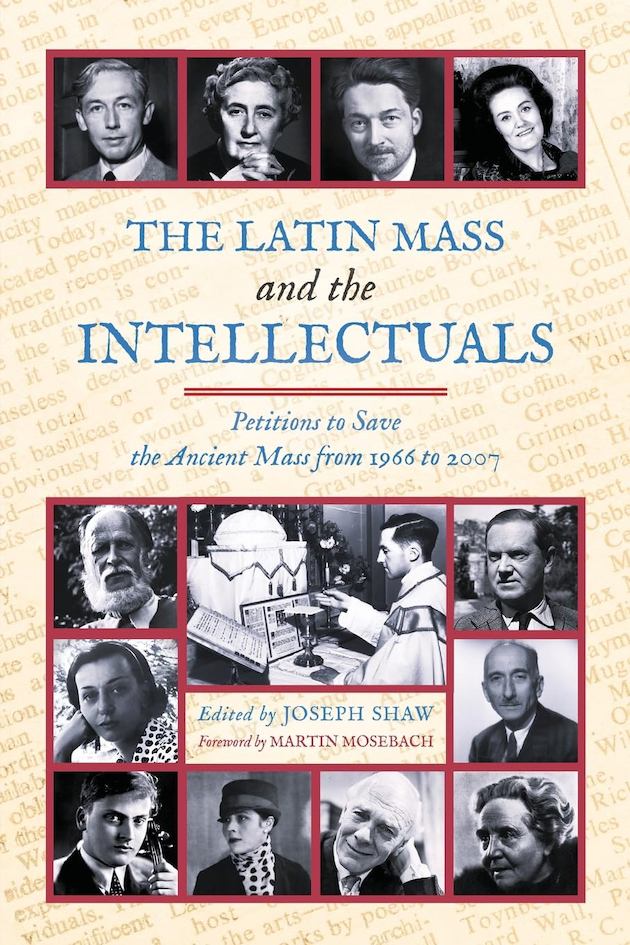

Joseph Shaw has assembled in The Latin Mass and the Intellectuals a book of essays that is a major new contribution in the English language to the history of those times. It focuses on the two major petitions in 1966 and 1971 that were submitted to the Vatican for the preservation of the Latin mass. The book also covers other petitions in subsequent years – but these larer examples were more specific, and the signatories were predominantly individuals and organizations involved in one way or another in the traditionalist cause.

That certainly was not true for the 1966 and 1971 petitions. The signatories included a broad range of distinguished representatives of the arts and sciences. Contributions in this book by Joseph Shaw and Fr. Gabriel Diaz- Patri list the signatories and explain their accomplishments and connections. Some of the names may be surprising: Jorge Luis Borges, Jacques Maritain, Graham Greene, Francois Mauriac, Giorgio de Chirico, Rene Girard – and many more. Perusal of their biographies shows that many were not traditionalist, conservative or even Catholic. Indeed, there are some representatives of the far left among them. What united them all was concern for the preservation of the historic artistic heritage of the West. By the way, those who became more directly involved in early traditionalism were also by no means drawn exclusively from the ranks of the political right.

A forerunner of these post-conciliar initiatives was an essay (included in this volume) written by Marcel Proust in 1904 when the anticlerical French government was supposedly thinking of banishing Catholic worship from the cathedrals and churches it had seized. That work pointed out the intimate connection between the purpose for which the gothic buildings were created – Catholic worship – and the art and architecture of the cathedrals. Proust’s essay later was consciously drawn upon by those who formulated the petitions after the Council.

The heart of this volume are the chapters on Cristina Campo written by Fr. Gabriel Diaz-Patri. An outstanding Italian literary figure, Campo had gradually become immersed in the Catholic mystical and spiritual tradition. She “converted” around 1964 – perhaps after having been present at vespers.

Certainly, between 1964 and 1965 something spoke to her, reaching her from infinite distances. She spent hours of churches. She sat meditating in the monastery of Tre Fontane, she attended vespers at Sant’Anselmo, perhaps unaware that almost 30 years earlier, in May 1937, Simone Weil had sat on the same pews … (p. 113)

But Campo sprang into action as the first liturgical changes were imposed. It is due to her efforts that both the 1966 and 1971 petitions came into existence.

(A)ll the testimonies agree that the driving force behind Una Voce Italia at that time was Cristina Campo, not only writing what the institution published but also personally doing most of the work on the practical side. On this occasion too (the publication of the 1971 petition-SC), the letter was due, to a very large extent, to her. Her international contacts with a cultural world that might be willing to give its support were crucial in the success of the project outside the English sphere (p. 201)

This book offers the first detailed account in English of Campo – at least up to the point of publication of the petitions. We would like to hear much more about the few remaining years of her life (she died in 1977). Happily, Shaw tells us that the chapters in The Latin Mass and the Intellectuals are but a selection from a forthcoming new biography of Campo by Fr. Diaz-Patri.

Fr. Diaz-Patri offers a second extended biographical narrative – of Bernard Wall and his circle, the organizers of the English side of the 1971 petition. I confess I found this account of the meetings and interactions of Wall’s friends going back decades less interesting than the Italian events involving Campo. Still, it was fascinating to read how much time people of those days could devote to discussion, how the serious exchange of thought had not yet been drowned out by the media torrent of our days.

What was the motivation for organizing these petitions? I think it was to witness to the irreplaceable, intrinsic “objective” value of the forms of the old liturgy. This was something that could be understood and appreciated aside from any personal commitment to the religion those forms expressed. Thus, these petitions form an important witness in a Church which presented (and still presents!) the changes in the liturgy as some kind of unanimously accepted divine revelation.

The actual effect of the petitions was of course minimal. The 1971 petition did obtain some narrow freedom for the continued existence of the old mass for the UK – although I read that subsequent to 1971 the Vatican sought at times to revoke even that limited exception.

Now, of course, these intellectuals may have been foolish to expect that these petitions would have any effect on the conduct of the Vatican. Their arguments at the time in fact backfired, opening them up to the “indictment” of being “aesthetes.” Amazing – for many centuries the Catholic Church had been the main patron of the arts, now, in the 1960s, expertise in and commitment to the arts had become an accusation, an unforgivable sin.

What held true for the petitions of 1966 and 1971 did even more so for the later ones submitted by traditionalist or conservative proponents. In at least one occasion the receipt of the petition was hardly acknowledged – let alone any response being given. It’s instructive to read, in the case of these later petitions, of the arrogant and underhanded behavior of the Vatican officials – including those supposedly tasked with looking out for the traditionalists. Indeed, the chicanery and confrontational attitude we now associate with Pope Francis and Cardinal Roche already were current – if displayed less systematically and openly – under John Paul II.

Martin Mosebach writes a remarkable foreword. For the first time in history, he writes, the laity rose up to defend the hierarchical, priestly, and sacral character of the Church – against an initiative launched by the priests! This book describes the battle for the Roman liturgy, and those who fought it were convinced it was the most important of the twentieth century – because the survival of the Christian religion was (and is) at stake.

Joseph Shaw’s informative preface describes a primary purpose of The Latin Mass and the Intellectuals: to honor the memory of the petitioners who sought to preserve the Traditional Latin Mass – especially Cristina Campo, “the foremost of them all.” He further claims that the minor relief obtained in the “English Indult” was a precondition for the expanded indults in 1984 onward. Well, one could argue about that – I think the actions of a certain French archbishop had far more to do with it. On the contrary, I would guess most people would consider the efforts of Campo, Wall and their friends to have failed. Yet the witnesses of these early petitions, like the early martyrs of the Church, can never be seen as failures. Their full influence will only be known in the course of generations. Their testimony to the truth and the power of beauty remains vital for us who live once more in an age of doctrinal collapse and official persecution. The Latin Mass and the Intellectuals is essential reading!

Related Articles

No user responded in this post