Winter in Wien – or at least late autumn in Vienna – a somber time of gray skies, chill winds and frequent drizzle. The dismal weather and the falling leaves prompt thoughts of death, of the end of things – so different from the frequent brilliantly clear, joyous days of Fall in the Northeast United States leading up to Thanksgiving. Yet the lights that begin to appear in early November at the Christmas markets scattered all over Vienna make all the stronger impression contrasted with the increasing gloom. You can get a real sense here why Christmas took on such extraordinary importance in the German lands.

Winter in Wien is the title of the last book written by Reinhold Schneider, a leader of the “Catholic Literary Renaissance “ in Germany. Written in 1957-58, it is a diary of a lengthy stay by the author in Vienna, at a time when the raw memories of the catastrophe of World War II and the fears of potential apocalypse of atomic war were very much alive. Winter in Wien is a dark, even despairing work, deeply pessimistic about the future of Man. Vienna, a place where the great course of European history seemed to have come to a final end, naturally lent itself to reflections on the last times. And Reinhold Schneider – like most authors of the Catholic literary Renaissance – was naturally a man fascinated by the extremes of human behavior– sacrificial resistance, heroic stances, dramatic conversions. He had written a memorable novella on Bishop Bartolome de las Casas; he had published underground essays of theological consolation during the National Socialist regime. In the bleak pages of Winter in Wien Schneider meditated on the end of civilizations and of history.

Yet, unless my memory is playing tricks on me, the most profound insight of this book lay elsewhere. Schneider was visiting a shop when a ridiculous toy – something like a jack-in-the box – caught his attention. And this cheap object suddenly was an epiphany for him. Yes, Schneider now knew that he indeed was in apocalyptic times. But our author had been entirely mistaken about the nature of the threat to the West. It was not Nazi or communist persecution or annihilation in an atomic holocaust. Rather, it was modern consumer culture with its the ludicrous products like that silly toy that were burying Western civilization. A burial ritual that reached its consummation in the “opening of the windows” to “modernity” by the Catholic Church only a few years afterwards. As another, perhaps more insightful author had written decades earlier:

“This is the way the world ends, not with a bang but with a whimper.”

Today, decades of EU prosperity have transformed Vienna into one of the minor outposts of the New World Order. The slovenly, casual dress of almost everyone is striking; you get the sense that 1970’s American fashion has been elevated into a uniform here. One evening, one of the main TV channels shows a film on the great poet Trakl, graphically depicting an improbable love affair with his sister; there followed a movie on the saga of an aging prostitute (a transvestite? – I didn’t watch long enough to find out.). A Volksoper production of Puccini’s Turandot has all the singers dressed as insects.

(Above) The baroque Mariahilf church reflected on one of the stores of Vienna’s main shopping street.

It’s all a strange contrast with ball dresses on display in the windows. They testify to the continuance (for tourism’s sake?) of social rituals whose purpose disappeared ages ago. Indeed, almost everything of interest here belongs to the past; the magnificent Habsburg art collections, the oversized buildings on the Ringstrasse, the many magnificent baroque churches, the musical life in the opera houses, churches and concert halls. Western Europe as whole is living off the legacy of an earlier age but nowhere can this be sensed as strongly as in Vienna. The Austrian Republic and the European Union have created nothing here.

(Above) The University – and the Jesuits’ – church, with the new and old altars.

Neither has the Conciliar Church, whose ravages are nowhere greater than in Austria. 50 years ago 90% of the population of Vienna – even if never a hotbed of the faith in recent generations – still identified themselves as Catholic. Today it is 40%. Religious practice is far less than what that percentage implies. In a magnificent baroque church one encounters only one or two visitors at any one time – half of them tourists. Sunday masses of the churches of the center of town are frequented mainly for the music. Again, one encounters the trappings of the past –the magnificent architecture, the masses of Mozart, Haydn and Bruckner, the splendid vestments – in a new environment entirely foreign to the culture that created them.

(Above and Below) the Votivkirche.

Perhaps the grandiose “Votivkirche” (Votive Church) on the Ringstrasse is more illustrative of the current spiritual situation of Austria than the perfectly maintained baroque churches of the older part of town. This grand neo-Gothic church was built in the second half of the nineteenth century in thanksgiving for Franz Josef escaping an assassination attempt. It had dedications from the Imperial family and from the nations that made up the Austrian Empire. Even at the time of its creation, however, there was criticism from “liberals” (in the original sense of the term) for whom the Votivkirche was a relic – if magnificent- of a faith that had vanished:

Already before me did a poet call you, the newest of cathedrals, “the Church without God.”

And truly so:

Perhaps, since you could be seen in your much-praised beauty,

Has hardly one heart throbbed within you in true faith,

Has hardly one knee bent in true devotion.

And so you tower,

Even if filled each day with the sound of organ and with clouds of incense,

With your flying buttresses

And your openwork spires,

Like a stone anachronism

Upwards out of the faithless present…

(Ferdinand von Saar)

The Votivkirche also had important connections with the Austrian military. All around the church are commemorative plaques and monuments – the legacy of two terrible world wars. And after World War II, the republic of Austria smeared its partisan political messages on the windows and walls of this church.

(Above) This plaque commemorates not soldiers in one of the two world wars but militiamen fighting a leftist uprising in 1934 – and perhaps others who died fighting a National Socialist coup attempt.

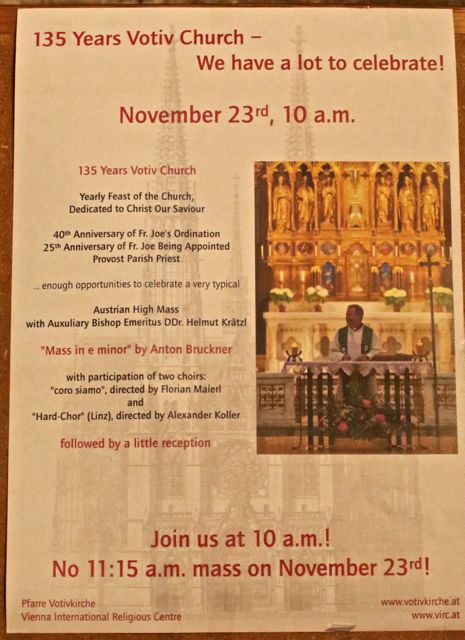

(Above) In the Votivkirche. (Below) The magnificent old main altar.

(Above) The renaissance grave (moved from a destroyed church in Vienna) of Count Nicholas von Salm, the heroic commander during the first siege of Vienna by the Turks in 1529.

But the post-war years have not been kind to the Votivkirche. In contrast to the baroque churches of Austria, nineteenth century neo-gothic architecture was held in contempt. Signs of neglect are everywhere, and the scaffolding outside the church serves as a welcome billboard leased out by the Archdiocese of Vienna. The congregation of this church, still sizable in 1950, has also dwindled away. Now it is the seat of an apostolate to foreigners in Vienna, led by “Father Joe” (naturally not an Austrian).

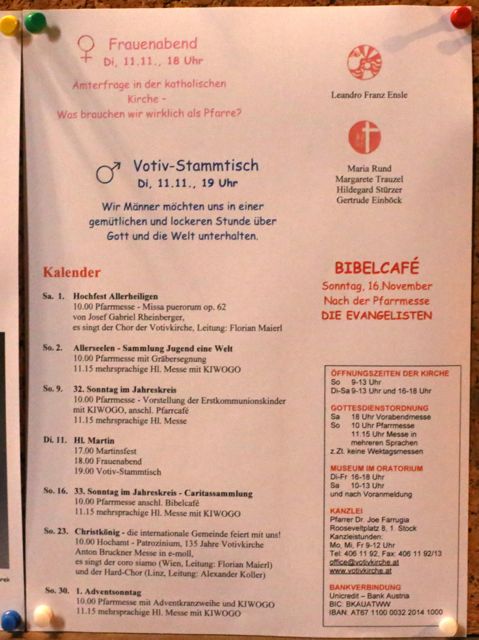

(above) An “evening for women” on “the question of offices in the Catholic Church” while the men discuss God and the world.

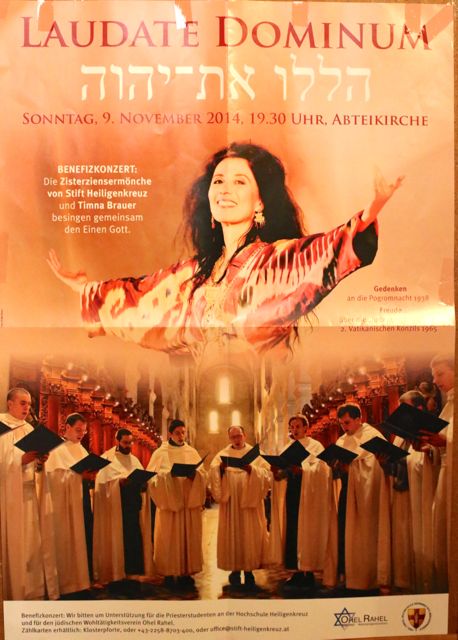

(above) “Father Joe”; (below) “The Cistercian monks of Heiligenkreuz monastery and Timna Brauer sing together to the One God.”

Truly, it seems that European culture has reached its end here! And yet, despite it all, there are still people kneeling and candles constantly lit before the images at the entrance to St. Stephen’s cathedral. The Christmas and Advent markets found everywhere are (still) called just that – not “holiday” or “seasonal” markets. One finds here and there signs of devotion to Blessed Karl of Austria. And in some less touristy, more out of the way cafes we find pictures of Emperor Franz Josef and Dr. Karl Lueger….

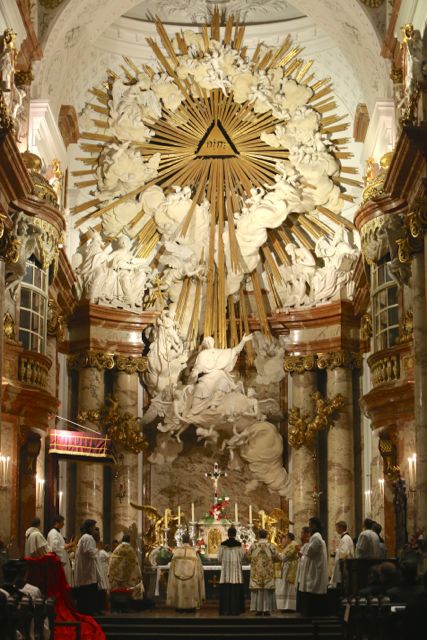

Finally, on our recent visit we experienced the wonderful solemn mass celebrated by Cardinal Burke. The magnificent Karlskirche of Fischer von Erlach was standing room only during the entire lengthy service. Several gentlemen stood about in uniforms reminiscent of the Empire. Families with sometimes noisy children attended without being greeted by angry glares or scolding (as is usual in the German-speaking world). Perhaps the Catholic culture of Austria is not totally a thing of the past, perhaps that which was confidently declared dead even in Franz Josef’s time can spring miraculously back to life. And the only place to start is a return to the fullness – in theology, morality and ritual – of the faith that made this culture possible in the first place

(Above)Solemn pontifical Mass with Cardinal Burke.

(Above) “Immaculate Virgin, intercede for Austria!” This shrine from 1936 in an ancient church is qualified as a relic of a prior time by a modern explanatory plaque.

Related Articles

No user responded in this post