Three exhibitions in New York City, modest in scale yet artistically of the highest importance, illustrate the breadth of Catholic influence in the arts in different nations and ages – as well as showing the effects of opposing religious movements.

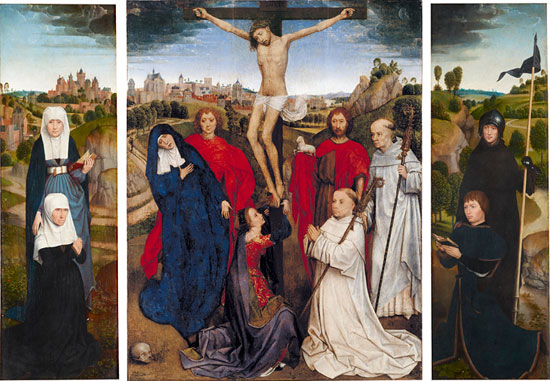

First, the Pierpont Morgan Library has dedicated an exhibition to the reunited panels of the Triptych of Jan Crabbe, a masterpiece by Hans Memling (above). The side panels have always been special treasures of the Morgan Library; the center panel of the Crucifixion and the the two rear images of the Annunciation (not shown here) come from museums in Italy and Belgium. The donor was the abbot of a Cistercian monastery near Bruges.

The crucifixion is situated against the backdrop of an extraordinary detailed land- and cityscape, overshadowed by a threatening sky. But what most attracts our attention are the depictions of the donors and their patrons. In keeping with late medieval mysticism, they directly participate in the drama of the passion. In particular the left panel is unforgettable. The aged Anna Willemzoon (the mother of abbot Jan Crabbe) is a marvelous depiction of old age; her patroness, St. Anne, places her hand on her shoulder and gazes forthrightly at the viewer. Yes, this painting is a triumph of close observation of reality, but at the same time is bathed in a mystical calm.

The exhibition also features other paintings and drawings of that era which provide a context to the Crabbe triptych. An excellent catalog (Editor, John Marciari) gives much additional information about the paintings, the artist and the practice of art in 15th century Bruges. The exhibit lasts until January 8, 2017.

PLEASE NOTE:

On Tuesday, November 15th, 7:00 pm at the Church of St. Thomas More (65 E 89th St.), Dutch scholar and curator at the Morgan Library & Museum, Ilona van Tuinen, will explore the hidden world revealed in this enchanting piece, as well as unravel the tangled tale of this sacred piece on the secular art market.(“Painted on the eve of the Reformation; dismembered and scattered on the art market: reunited in New York City”). Discussion will take place in the Rochester Room. For more information, see HERE.

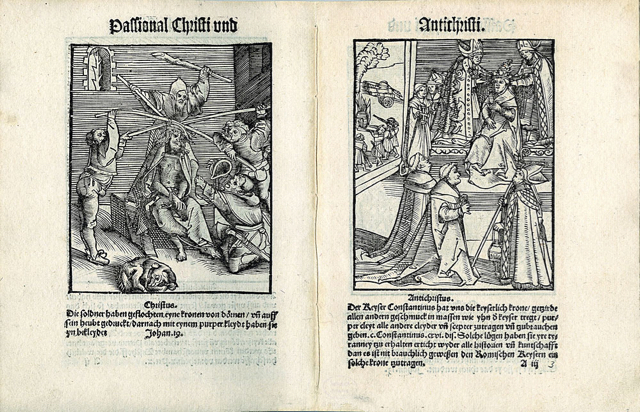

A second exhibition currently at the Morgan is dedicated to Martin Luther and the Reformation. All kinds of curious objects are included: Tetzel’s treasure box for his indulgence money, a chasuble allegedly worn by Luther (after his breach with Rome). but the heart of the exhibit consists of books, pamphlets and other original printed witnesses of the Reformation. These documents witness to the essential differences that quickly emerged between Luther and his followers and the Catholic Church. A development that almost immediately blossomed into fanatic hatred of the the papacy, the Catholic Church and the mass. Pope Francis and his entourage and the Swedish Lutheran church recently have found very little remaining that divides them, but we can take this as the harmonious encounter of two groups of modern unbelievers. To apply these conclusions to the 16th century is an insult both to the Catholics of that age and Martin Luther and the early Protestants. They deeply believed in the positions they so vehemently asserted! What also becomes clear from this exhibition is that the rapid spread of Protestantism was directly connected with availability of new printing technology.

The exhibition also illustrates the impact of these titanic struggles on the arts. We discover some remarkable works created in the German Catholic world on the eve of the Reformation. A tender Madonna and child by Lucas Cranach – an image the artist repeated frequently for Catholic patrons even after he had become the main visual propagandist for Luther. Or the unique, extraordinary mystical image (above) of Christ and Mary ( The Virgin? Mary Magdalene?).

All this was to change in the Reformation. The exhibition claims that Luther was not personally opposed to the arts, but the spirit of the Reformation certainly called them into question. Art became increasing didactic in nature. There were widely circulated portraits of Luther and his wife – but they were also understood as statements again clerical celibacy. The attacks on the papal “Antichrist” in word and image grew wilder and wilder. (see below) The result was clear – Germany lost its formerly leading position in painting and sculpture for generations; only after 1600 did a modest revival commence. (Exhibit extends to January 22, 2017)

Finally, the Frick Museum is currently displaying an extraordinary example of Italian baroque art of around 1660: Guido Cagnacci’s Repentant Magdalene. (Above) Some aspects of Renaissance and baroque art are undoubtedly foreign to the Catholic “man in the street” of today: a voluptuous naked Magdalene, having cast off her meretricious finery, is directed by her sister Martha on the right path, while an angel drives out a demon and the courtesan’s servants flee in confusion. It all seems a mysterious, confusing tangle of bodies – dare we use the term “surreal?” Yet the Renaissance and Baroque ages loved such complex allegories. And this painting was not a fringe product but was commissioned in Vienna by the pious emperor Leopold of the German (Holy Roman) empire. Yes, Catholic religious art in its greatest ages had a most extraordinary range – perhaps too great for the sensibilities of modern piety! But in fact this painting reminded me of the efforts of certain modern artists who seek to revive “classical” and allegorical painting. (e.g. Leonard Porter, Michael Fuchs)

Description of the exhibit HERE. The painting will remain on display until January 22, 2017.

Related Articles

No user responded in this post