Today a friend asked me for the contact information of Helmut Rückriegel; I soon found to my great sorrow and surprise that he had died on January 25 of this year! I unfortunately only had a few occasions to meet Ambassador Rückriegel. He would visit New York where his son lived. I would meet him in a restaurant in the company of his friend Arkady Nebolsine. Helmut Rückriegel was a true Christian gentleman. A man of great culture, he had represented his country in various assignments – notably in Israel and Thailand. Possessed of a keen intelligence and a great sense of the real, he had the ability to understand and appreciate the merits of other peoples and cultures without falling into the servile obsequiousness so typical of the West and particularly of Germany today. Devoted to the Church and to the Traditional mass, he was utterly without the “churchy” Catholic’s cant and fawning airs. Ambassador Rückriegel had put his practical talents to use in promoting the Traditional Latin Mass – he held a leading role for years in the Una Voce Federation. To me he seemed a reminder of a bygone age, of the former greatness of German culture – which in its great days had sought to comprehend and embrace all the cultures of the world. I regret so much that through my own fault I had not had the chance to get to know him better!

Martin Mosebach has written the following obituary.

Obituary for Helmut Rückriegel by Martin Mosebach

An extraordinary man has left the earth. Standing at the grave of Helmut Rückriegel his friends conceive the whole truth of the discernment that with the death of a man there is a whole world that perishes. What pertains to everyone is most evident for such an overabundant nature as it was with our deceased friend Helmut. He was allowed to live a long life, and, we can say, to live in mindfulness and intensity. He finished the wine of life completely and entirely, including even the very last and then most bitter drops. Furthermore it was granted to him to maintain his entire strength of mind until his last moment; in complete alertness he witnessed his time and all its phenomena until the last moment. His participation in the world was insatiable; he was a pious Christian – the archaic term ‘piety’ in its comprehensive meaning like the antiquity knew it – was fitting for him. A life in the presence of the supernatural and a joyful discovering of this supernatural in the inexhaustible statures of the created world – but without suppressing the reality of the mortality of all life on earth, he lived as if there was no death.

Until his painful last sickbed he was seized with the fascination of languages – recently he started to learn Turkish, a language that is extremely far from all Indo-Germanic familiarity – joyfully entering into a totally different kind of thinking and feeling. I always wondered why he, whose sense of language was infallible, did not write himself. But in return his sentiment for the great German poetry was so profound that the verses of Goethe and the Romantics, of Hölderlin and Stefan George constituted deeply and totally his inner life. He was the reader and reciter that poets desired, drawing from a great pool effortlessly the most remote lyric creations to engender an awakening to melody and life.

His artist’s nature became apparent in the invention of his garden that he created in Niedergründau, the village where he came from, after the end of his working life: he cultivated rambler roses, growing into the old, partly withered apple trees high as a house, to create real snow avalanches of white blossoms; in May and June they were phantasmagorias of surreal, sheer beauty. Here, the gardener who planted hundreds of sumptuous roses, turned into a wizard. ‘Il faut cultiver son jardin.’ are the last words of Candide, Voltaire’s wicked satire in which the hero, after having underwent the horrors of a world falling to pieces, is forming the conclusion of his experiences. And it was in this awareness that Helmut created his garden. The experiences of this great connoisseur of the art of living had made him learn, no less clear than Voltaire’s Candide, that the earth is not a peaceful place, not a paradise.

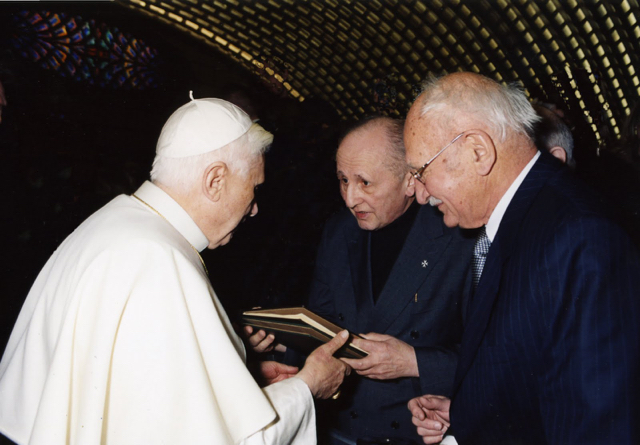

As a pupil and young man during the years of Nazism he thanked his teachers for the discernment that Germany was ruled by criminals; in these years he also experienced the Catholic Church as a place of resistance against the despotism. As a diplomat he travelled widely; but his most important positions for him were in New York and Israel – in the Holy Land, this small spot of earth, where also in his life all spiritual and demonic forces that agitate us as well today, collide; there he found the proximity of the truth of his faith, especially there, where it seemed to be completely unreachable. And very early he discovered for him the obligation to serve the Roman Catholic Church, his mother, for whom he saw himself as a faithful son, in her great crisis in which she had fallen after the Second Vatican Council. Helmut Rückriegel, who loved the oriental Churches, especially the Orthodoxy, the friend of many Jews, who – together with his friend, the great Annemarie Schimmel, admired the Sufism; he was a Catholic, as ‘the tree is green’ to say it with a word of Carl Schmitt. From his universal culture, from his enthusiasm for the masterworks of language, from his detailed knowledge of history and the cultures of the world Helmut Rückriegel was convinced that the Roman Church was – by its cult which has been transmitted from the late antiquity – a melting pot of all beauty and holiness that is possible on earth. In a decades-long friendship with Josef Ratzinger, Pope Benedict XVI., he helped to ensure that the Church did not completely abandon this treasure that belongs not to her alone, but to the whole mankind.

Helmut Rückriegel the diplomat must occasionally have been rather undiplomatic – he was full of passion, a battler who did not spare himself and his adversaries. A man made for being happy – but still often enough desperate of the vainness of all struggles of the best, putting up resistance against the spirit of the times. The old Helmut Rückriegel did not become wise of age – a wonderful trait he had and that conjoined him with his younger friends. A consistent one, also in his matrimony that lasted nearly fifty years: after his rich life that she shared for so long with him, Brigitte Rückriegel accompanied him faithfully unto death – for this long companionship and the synergy during the working years in many positions she is, as she told me, profoundly grateful, and Helmut’s friends have today to be grateful to her for all that she did for him, especially during the darksome days.

The cosmopolitan German patriot Helmut Rückriegel embodied the best aspects of Germany; to have known him is for me and certainly for many others an infinite well of encouragement and hope.

Related Articles

1 user responded in this post