1537 was a dire year for the Catholic Church or, as it was said at that time, for Christendom. Rome was still staggering after the sack of 1527. The Turks were advancing by land and by sea. Worst of all, Protestantism continued to advance by leaps and bounds. It had swept across Germany and Scandinavia. It was now beginning to surge in the Low Countries, in France and in French Switzerland. England had thrown off the authority of the pope and now the English shrines and monasteries were being liquidated.

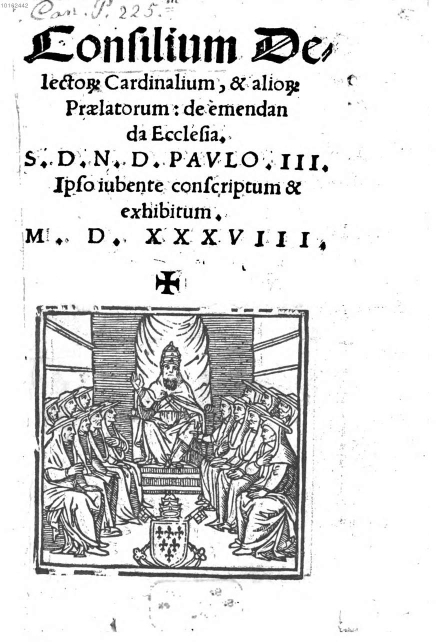

In 1536 Pope Paul III (1534-49) summoned a commission of Cardinals to advise on dealing with the “root causes” of the seemingly overwhelming crisis. The result in 1537 was the report Consilium …de Emendanda Ecclesia, an unsparing critique of the abuses in the Church. The authors included some extraordinary men, including Cardinals Pole (subsequently Archbishop of Canterbury under Queen Mary and at times a leading candidate for the papacy) and Carafa (later Pope Paul IV).

(Mr. Nicholas Salazar has taken the trouble to prepare the following translation of the first paragraphs of the Consilium – I have tweaked it and apologize for any distortions thereby introduced.)

Council of Select Cardinals and Other Prelates

On Reforming the Church

Most blessed Father, it is far beyond our powers to explain in words what great thanks Christendom ought to give to our perfect and supreme God for having made you pontiff in these times and having put you at the head of his flock, and for having given you such a mind as you have, that we may at least hope, in thought, it will be able to obtain those graces which it owes to God. For, as we see, the Church of Christ is tottering, nay has nearly fallen headlong. That illustrious Spirit of God, however, by which, as the prophet says, the power of the heavens is confirmed, has decided through you to place his hand under this ruin, and to raise her to her former loftiness, and to restore her to her former beauty. We can make a most certain interpretation of this divine sentence, for, having been summoned by you, Your Holiness gave us the command to point out to you–taking no account of either your or anyone else’s convenience or advantage–those notorious abuses, even plainly very serious diseases, under which for a long time now the Church of God and particularly this Roman Curia has labored. Through which it has been brought to pass that, gradually, little by little, as these plague-bearing diseases grew more serious, she has drawn down upon herself this great ruination that we see. Instructed by the Spirit of God, Who, as St. Augustine says, speaks in hearts with no noise of words, Your Holiness correctly knew that the beginning of these evils was the fact that some of your predecessors, “with their ears itching,” as the Apostle Paul says, “heaped up for themselves teachers according to their own desires.” Not, as they ought to have done, in order that they might learn from them, but rather in order that, by their partisanship and cunning, there might be found a means by which that which was pleasing might be permitted. So it happened – apart from the fact that fawning follows all power, as a shadow follows the body, and truth has always found access to the ears of princes very difficult – that the experts who were instructing the Pontiff immediately proclaimed that he was the lord of all benefices. Therefore when, as lord, he lawfully sells that which is his own, it necessarily follows that the Pontiff cannot be charged with simony. This is so because the will of the Pontiff–whatever it may be–is the rule by which his operations and actions are directed: as a result of which invariably whatever is pleasing is also permitted.

Now the Consilium squarely identifies as the foremost source of the evils afflicting the Church the conduct of the Vatican, specifically, the assertion of the Pope’s arbitrary, (lawless) power, that the Pope can do whatever he wills. A by-product, but also a cause of this abuse was a Vatican culture of sycophancy and intrigue. Of course, in the 16th century what the Popes strived for was, in the first instance, centralized arbitrary power over the worldly possessions of the Church, not over doctrine or liturgy. The result of these practices, however, was a vicious, secularly minded Papal court and a largely incompetent episcopate throughout most of Europe. It was this decayed clerical establishment that by its outrageous behavior largely contributed to igniting the Protestant Reformation and then proved incapable of confronting it.

The rest of the document deals more with more specific issues. Yet some of these criticisms also remain extremely relevant to our time: such as the disastrous effect of the mass ordinations of unworthy and immoral clerics or the impact of too liberal dispensations from the law.

Note, in those pre-ultramontane days, the openness with which the conduct of recent popes is castigated. The authors were unrestrained by fear of being accused of “criticizing the Pope” or “giving scandal.” Indeed, the text of the Consilium was almost immediately leaked. The reformers republished it gleefully, furnished with their own notes. Yet the authors thought – correctly – that declaring the truth far outweighed the impact of any “scandal’.”

The relevance of the Consilium’s analysis to the papacy of Francis and its revived ultramontanism is of course evident. Yet the Consilium is not some kind of 16th century Dubia. For starters, the Pope himself commissioned it. The authors were among the leading cardinals of the Vatican, still holding important offices. And whatever had been the misdeeds the popes of that era – and there were many – undermining Catholic morality in the exercise of the teaching authority was not one of them.

The abuses spelled out in the Consilium were not immediately corrected. Indeed, in many respects Pope Paul III and his Farnese family continued to be among the worst offenders. Yet gradually many changes did materialize. And beyond the immediate results, the Consilium stands as a monument to the honesty and willingness to reform of the much-maligned Renaissance Church. For the beginning of reform is the willingness to tell the truth and acknowledge one’s own faults. Can we claim that the Church of our day is capable of this?

Related Articles

No user responded in this post