In the first installment of these historical reflections, I briefly reviewed the triumph and maturity of “ultramontanism” in the Catholic Church. Fundamentally a defensive strategy, it aimed at block-like unity, centralized control and absolute subordination to superiors. Especially up to 1945, its catalogue of achievements was remarkable. Yet, like all defensive stances, it could not be prolonged forever. At some point a counterattack must be undertaken – for otherwise the enemy, having familiarized himself over time with a static opponent, will find a path to break through….

The Second Vatican Council convened in 1962. In no prior council had both the freedom from overt secular control and papal dominance over the proceedings been so assured. 2) The course and outcome of the council was determined by a new alliance of the papacy with internal progressive forces. Paul VI then enjoyed almost unlimited scope of action in implementing the council throughout the Catholic world.

The management of the Council and its subsequent implementation were truly the greatest triumph of ultramontanism. For no previous pope had radically and systematically changed the liturgy and the forms of Catholic piety (e.g., the rules governing fasting, the architecture and decoration of churches) virtually overnight. Paul VI found active supporters for his mission of change. A whole legion of clergy was inspired to forcefully drag into the modern Church the benighted sectors of the laity and their own less “enlightened” fellow clergy and religious. But, on the whole, resistance was minimal – so effective had been the inculcation of ultramontane obedience over the generations. Of course, the customs and traditions of the Church had likely lost their grip on much of the Catholic world through the ultramontane understanding of obedience to authority and adherence to legal rules as the source of their legitimacy.

But even while still in session, the Council had unleashed forces that shattered the closed ultramontane world. For the progressive clergy, empowered by Paul VI, undertook to directly reverse the theology, teachings on personal morality and the governing structures of the Church – all the things that hindered complete reconciliation with the world. For internally, the Council and its aftermath may have been revolutionary. But viewed from outside, these changes were completely conformist, as the Church adopted the worldview, vocabulary and even the dress of the secular world of the 1960’s. The guiding Conciliar principles of aggiornamento and “reading the signs of the times” had in fact subordinated the Church to secular society far more thoroughly than had been conceivable under the European monarchies of the 18th century, the Holy Roman Empire of the Gregory VII’s day, or the Roman empire in the 4th century. None of these historical powers had disposed of means (such as news media in the modern sense) capable of reaching into the life of each individual Catholic. Truly, it was a new, monumental “Constantinian shift!” And it was in these very years of the Council that the Western establishment’s attitude to the Church began to progressively change from a politically dictated posture of respect to an overt, intensifying hostility: starting with Rolf Hochhuth’s 1963 drama The Deputy and culminating in an across-the-board critique of “retrograde” Catholicism, above all, the Church’s teachings on sexual morality.

These developments came to a head with the storm over Paul VI’s 1968 encyclical on contraception, Humanae Vitae. The pope could not obtain obedience to his decree – not only from the “rebels” but also from the religious orders, Catholic universities and even entire episcopal conferences. For Paul VI found himself confronting not only internal opponents, but also modern “civil society” and its media, which stood behind the rebellious elements. It was a previously unthinkable breach in ultramontane discipline. Truly, the Council, which had marked the high water mark of ultramontanism, had now administered to it its greatest defeat!

As to papal authority, the result was deadlock. Paul VI would not withdraw his encyclical – but neither did he attempt to insist on its enforcement. The same impasse was true of many other doctrines and rules of the church. A state of permanent, unacknowledged “civil war” from now on prevailed in a Church in which a substantial part of the Catholic establishment either denied or understood in a new non – literal way what had been previously fixed and certain doctrine. To give just one example, papal infallibility – a foundation stone of ultramontanism – was widely either denied outright (Hans Küng’s Infallible? – an Inquiry (1971)) or, more subtly, had its origins called into question (Hubert Wolf ’s The Nuns of Sant’Ambrogio (2013)). The progressives did not necessarily see any need of respecting the “views” (Eamon Duffy) of the Vatican.

Of course, some leaders of the Church – and not just those resident in the Vatican – continued to resist these interpretations and tried to preserve Catholic doctrine as traditionally understood. Popes John Paul II and Benedict took numerous actions and made frequent statements on the liturgy, Catholic education, Catholic doctrine on sexual morality, etc. Like Humanae Vitae, these were mostly ignored. Disciplinary measures to impose order on the Jesuits (under John Paul II) or on American religious sisters (under Benedict) ended in capitulation by the Vatican. For there was very little the popes could do. To directly confront the progressive establishment would in short order draw the media into the fray. That would reveal clearly that the alleged Conciliar reconciliation of the Church with the modern world had failed. Moreover, I suspect the popes feared that a large portion of the laity would likely follow the media.

This reluctance of the popes during this period (1970-2013) to act against the progressive forces and their institutions was not just dictated by tactical considerations. All these popes shared at least to a limited extent the opinions and goals of the progressives. And they were also desirous of a favorable presentation by the media. Peter Seewald’s biography of Pope Benedict reveals this obsessive concern of the Vatican with the pope’s image in the press.

There was no longer any question of recreating the pre-conciliar unity of belief and practice. At most, the popes could achieve a “tilt” in the direction of Catholic tradition – mainly through episcopal appointments. Even here the results were erratic. Yet, within the constraints outlined above, under John Paul II there was an “ultramontane revival.” John Paul II gained prestige from his role in the collapse of communism and his charismatic public persona. He adopted to a great extent the style of secular politicians and regimes. That even extended to features imported from the repertoire of the totalitarian states of the Eastern bloc (e.g., youth days and festivals; massive orchestrated public appearances). The result was a renaissance of the papal image – appealing to so many at the time. The cult of “John Paul the Great” was born.

The “neo-ultramontane” wave generated an immense amount of activity on the part of the partisans of the “Polish Pope” – especially in the United States and mostly among those outside the clerical establishment. Papal infallibility was reemphasized by these activists and now extended far beyond the 1870 definitions. The election of the pope was now “God’s choice.” The articles contained in Civilta Cattolica, because they were cleared by the Vatican Secretary of State, took on an aura of infallibility. The infallibility of Humanae Vitae was proposed. The stalemate of the post-Conciliar Church was recast as a struggle between papal authority and “dissenters.” Although such positions remained unofficial, they are indicative of the pro-papal surge under John Paul II.

The new papalism, however, had to account for the tolerance of John Paul II for the progressive forces. The explanation that was found was the Pope’s need to avoid “schism.” This is, of course, a degenerate ultramontane understanding, in which preserving the external appearance of unity takes precedence over ensuring its actual substance.

Another aspect of the neo-ultramontane era – sparked by the style and restless activity of John Paul II – was the obsession with the political aspects of the papacy and the Vatican. A whole legion of reporters, “information entrepreneurs” and, later, internet personalities concerned themselves with the internal affairs of the Vatican. In considering any issue of Catholicism it became usual to include speculation on Vatican personnel moves. Actions having the greatest importance for each individual Catholic were portrayed as the product of changes in the leadership of, and even within, Vatican dicasteries. Do I need to mention all the Vatican novels published in this era? – some of them informative, others ludicrous. Whatever might be the Vatican’s actual authority over the Church, this focus on Rome demonstrated that an unhealthy ultramontanism was alive and well.

We should mention at this point the ever-growing bureaucratization of the Church after the Council. Despite all the disorders within the Church, offices, “apostolates” and administrators increased. As the ranks of clergy and religious declined in the post-Conciliar chaos, the number of lay employees grew exponentially. The clergy were also assimilated to bureaucrats. A retirement age was now set for bishops, and they increasingly were moved about from diocese to diocese. At the local level, term limits began to be imposed on pastors. Added to this mix was an extreme degree of legalism. The result was an increased perception of the Church as a secular organization like the United Nations, a governmental agency, the EU headquarters or, later, a very large NGO (non-governmental organization)

Towards the end of John Paul II’s papacy, and during the whole of Benedict XVI’s reign, the Church and in particular the Vatican had to face ever increasing difficulties. The fundamental issue of the decline of belief and practice of the Faith within the Church herself had not been resolved. The Vatican bureaucracy became a cesspool of careerism, incompetence, and financial corruption. The documentation that has been disclosed on the career of Cardinal McCarrick reveals how little John Paul II understood of the appointments he was charged with making. The scandals of sexual abuse, the conduct of the leaders of the Legionaries of Christ and financial misdeeds at the Vatican opened up new fronts for relentless secular attack on the Church from 2002 to the present day. Pope Benedict was utterly unable to contend with either the media or his own Vatican bureaucracy. Indeed, the pope’s enemies in the latter organization resorted to outright treason to block Benedict’s initiatives.

Faced with rising tide of challenges, these popes seem to have slipped into a fantasy world – at least if popular biographies are any guide. According to George Weigel’s Witness to Hope (1999), John Paul II seems to have been of the opinion that his innumerable voyages thorough the world were having major political effects (only in Poland was that conclusion perhaps justified). In Seewald’s biography (Benedict XVI: ein Leben (2020), pope Benedict is reported to have thought, upon ascending the papal throne, that all issues of the Church already had been favorably resolved by his predecessor. To quote another example, at several Vatican-sponsored conferences it was proposed that excess priests be shifted from the developed to the third world – this, at a time when the churches of these “advanced” countries were in fact relying more and more on imported African, Asian and Latin American priests.

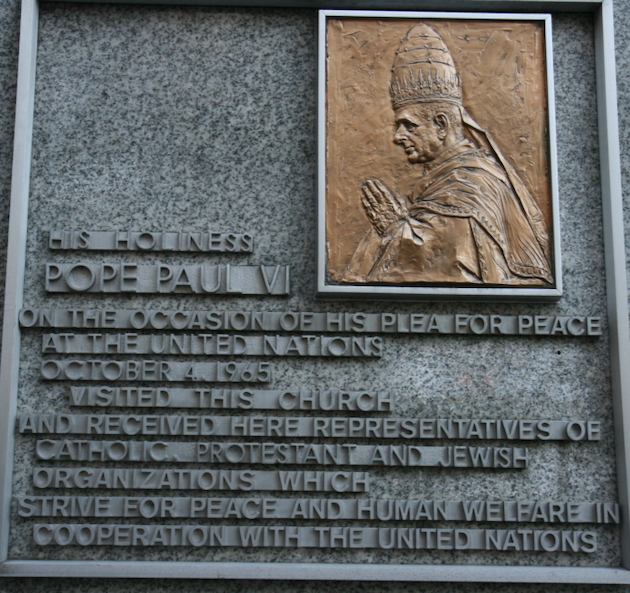

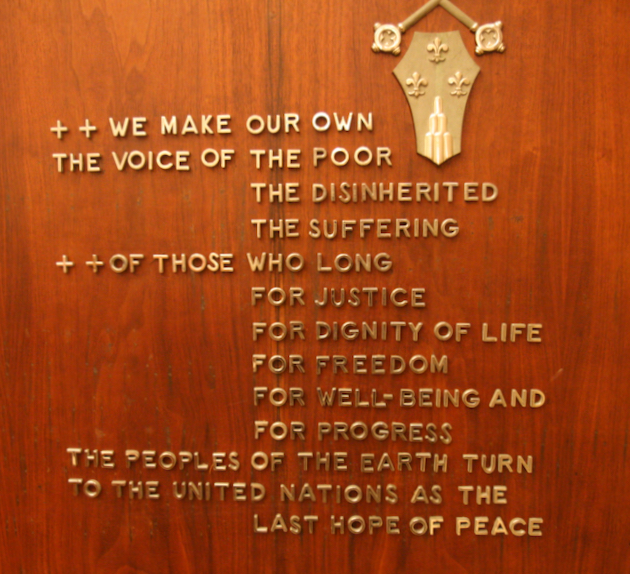

In the same vein, as the popes’ real power within the Church declined, papal visions of global leadership grew. The bishop of Rome now was described as the “pope of all mankind,” a kind of worldwide spiritual advocate. Thus, John Paul II presided over interfaith assemblies at Assisi. Pope Benedict lectured in abstract terms on the relationship of faith and reason to the unbelieving German parliament.

Most importantly, the need for a renewed evangelization – now primarily within the Church herself – still had not been met. The opening to the world had been a one-way street in which the world instructed the Church. The marriage of the Council with ultramontanism had produced a culture that was far more provincial than the ghetto of 1958 so derided by the advanced Catholic circles of that time. The art and music of the Church by 2013 was either kitsch or uninspired copies of modern aesthetic orthodoxy. The increasing lack of funds limited even that activity.

The papacy had indeed survived the turmoil it had itself created in wake of the Council. But the Conciliar papacy had not preserved the Church’s unity in doctrine and practice – the reason ultramontanism had been advocated in the first place. The Vatican increasingly functioned as a mere administrative center, while all kinds of developments, heterodox or not, proceeded autonomously. In 2013 Pope Benedict resigned. It was a crushing blow to the papacy and absolutely unimaginable under pre-conciliar ultramontanism.

- The window is contemporary with the encyclical. Mater et Magistra is also noteworthy in the history of ultramontanism. William F. Buckley’s public disagreement with the pope’s conclusions – on economics – was up till then virtually unheard of.

- With the exception of any understandings that may have been reached prior to the Council with the Soviet Union. But in avoiding a specific critique of the communist world the Council was only following the lead of the Western secular establishment which, by that time, had largely committed to an ideology of “peaceful coexistence.”

Related Articles

No user responded in this post