The Art of the Book in the Holy Roman Empire 800-1500

Exhibition at the Pierpont Morgan Library (through January 23)

The Holy Roman Empire, despite many ups and downs, was a key force in European art, culture and politics between 800 and 1806. This exhibition basically covers seven centuries of book illumination in the empire from 800 to 1500. The exhibition focuses on the Holy Roman Empire as it existed around 1500, minus the Netherlands – in other words, Germany and German cultural areas. This way the exhibition achieves cultural and national unity. For to cover all the territories under the domination of the empire at its greatest extent – by adding the northern Netherlands, eastern France, and North /Central Italy – would make the exhibition a general history of Christian European culture. It is impressive that the exhibits are drawn mainly from the holdings of the Pierpont Morgan library itself, as supplemented by loans from other American institutions.

The exhibition also serves as a good course in the political development of the empire. At first, the Holy Roman emperors themselves played a dominant role in patronage, commissioning works from monasteries and major ecclesiastical centers. This was gradually supplemented and succeeded by the growing patronage of the nobility and the princes. In the 14th century the first real permanent capital of the empire was established in Prague, in the face of growing rivalry with Vienna and the Hapsburgs of Austria. Finally, at the end of medieval times, came the flourishing of the great imperial cities – Nuremberg, Augsburg, Strassburg – as producers of art. Naturally there was much overlap: Emperor Maximilian I, who died in 1519, was one of the greatest patrons of all and the ecclesiastical center of Mainz – which never quite became a free imperial city – played a major role around 1450. Indeed, on display in this exhibition is a Gutenberg Bible (the Morgan Library has three!) printed in the same city of Mainz -using a technology that in the course of time would end the illuminated manuscript tradition.

The art on display consists primarily of illuminated manuscripts as well as book covers and liturgical vessels in precious metal. Now one must understand that in the first centuries covered by this exhibition (800 to 1200) the so-called “fine arts” of architecture, painting and sculpture were not perceived as superior to “applied arts” like book illumination or goldsmiths work. Just as much care was given to the precious book covers, liturgical vessels, reliquaries – as well as to the manuscripts – as was given to the churches that contained them. In other words, what we see in this exhibition are the main products of the art of these early medieval periods.

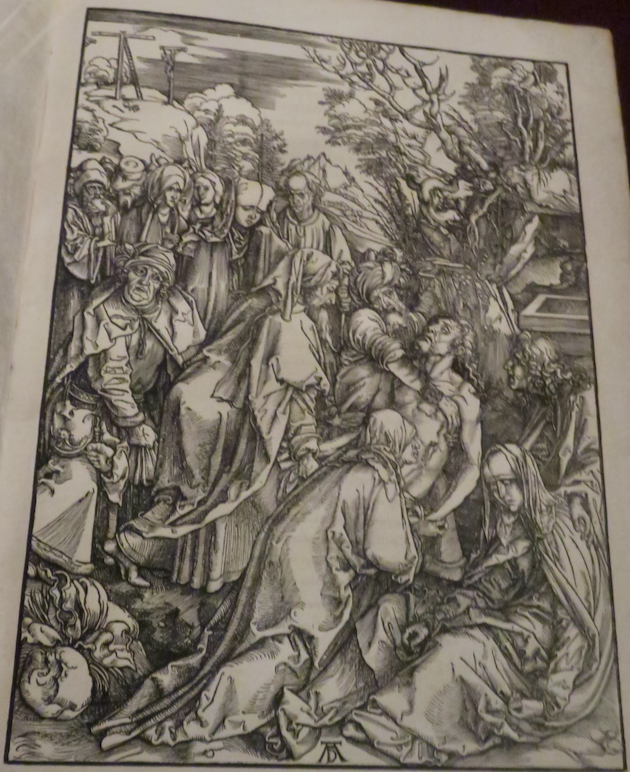

We see also a transformation of the role of the artist, his art and his patron. In the first centuries lavish illustrated manuscripts are encased in gold covers. These are primarily commissions by the imperial family themselves and the artists are primarily monks at the major monasteries. Later, monasteries and noble families joined the imperial families as major patrons of art. From the 13th century onward lay professional artists played an increasing role in illustrating manuscripts. By the 15th century professional artists had become the dominant force in free cities like Nuremberg and an export trade came into existence. A growing interaction developed between book illumination and the new art of printing. Finally, we see the artists of the Renaissance – like Albrecht Dürer – bringing their individual creativity to bear in exploring entirely new approaches to traditional themes.

Do not these masterworks demonstrate to us the importance the written word once had? Today a word appears on Outlook and – if it even survives the spell checker – shortly thereafter may vanish forever. Yet in illuminated manuscripts the word is carefully preserved for all time. This is particularly true of the early medieval period. But even towards the end of the centuries covered by this exhibition, we see the extreme care with which books, both printed and handwritten, are prepared. We see also the cultural importance of Latin – the language of most of the manuscripts in this exhibition. Throughout seven centuries it served as a unifying factor – and of course was always the Church’s liturgical language. After 1200, books written in the vernacular (German) start to appear – and in the 15th century we find one Czech example. Yet Latin retained its primacy throughout.

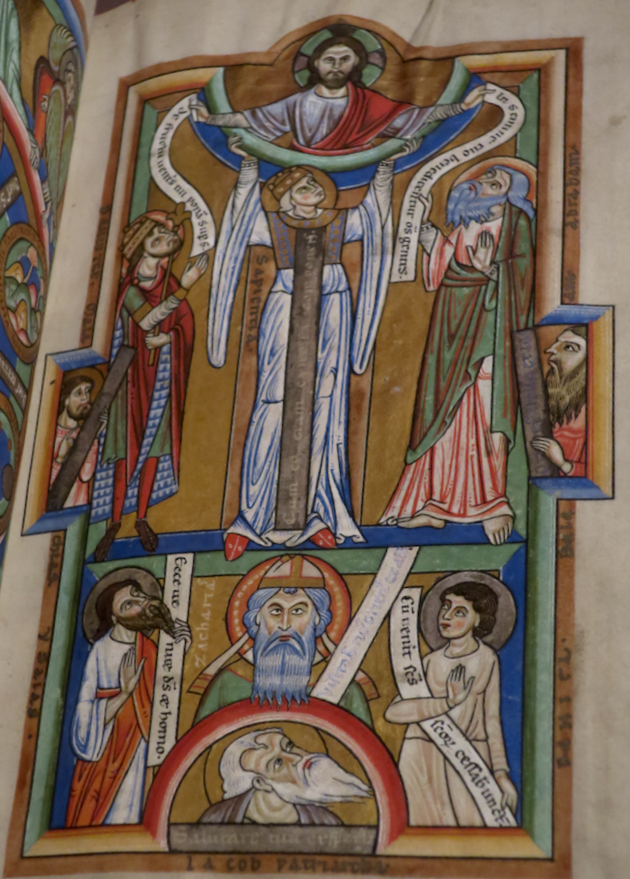

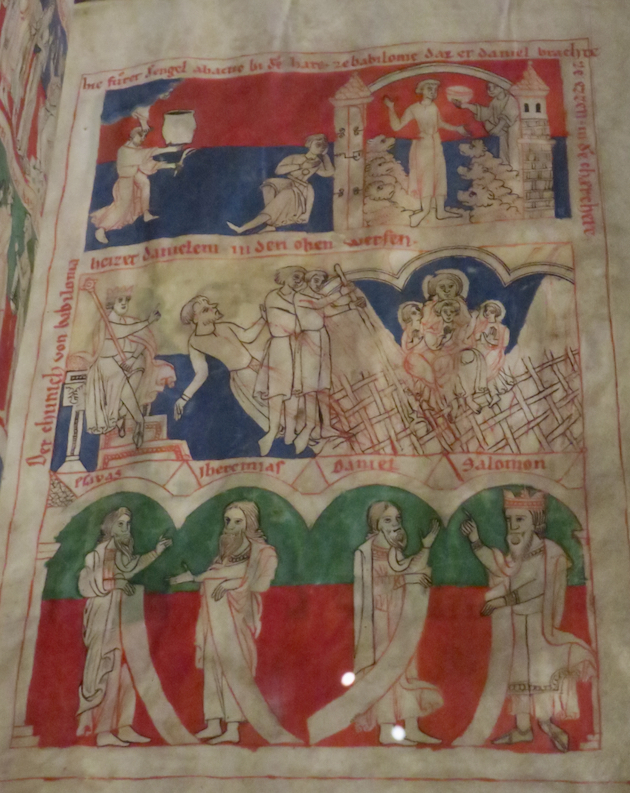

It may be obvious, but I still need to point out that in all the seven centuries covered by this exhibition, the Catholic Church was the overwhelmingly dominant artistic force of the “Holy” Roman Empire. In the later centuries secular works do increasingly appear but were often Christian allegorical or philosophical treatises. From the end of the Carolingian age to the Renaissance, artists interacted with the same elements of Christian belief: the Old and New Testaments, the lives of the Saints, edifying parables and allegories. The Morgan exhibition does point out the Christian meaning of many of the images and symbols of the objects on display and the role of certain items in church ritual (e.g., processional gospel books, large format books of chant).

The works these artists created over so many centuries of course show great stylistic differences and even artistic development; the Christian intellectual foundation, however, remained the same. One also cannot speak of “progress” – is a Dürer print superior to an Ottonian illumination? This is the nature of Western traditional art, which modernists – either in art or liturgy – cannot understand: the tradition remains the same even if each age makes its own contribution in creative dialogue with the permanent elements of the culture.

The visitor can experience this unity first hand today if, proceeding beyond the timeframe of this exhibition, he visits the cities and monasteries where the books presented at the Morgan Library were created. Such as the immense baroque monastery of Weingarten in south-west Germany. Or St. Gallen – now infamous – which was built later and is more restrained, but has an incomparable library. Only Reichenau preserves somewhat the appearance of the abbey buildings as they existed when the magnificent manuscripts in this exhibition were created in Ottonian times. The city of Regensburg perhaps most perfectly illustrates this continuity – with sacred edifices dating from the 8th to the 18th centuries. The Holy Roman Empire – or at least parts of it – remained true to its Christian Mission even to the end of the 18th century.

It is this diversity in unity which distinguishes the art of the West – at least before 1800. The Holy Roman Empire was preeminently representative of such a culture, lacking as it did strong central political institutions throughout most of its existence. But this “Holy” Empire always had one clear focus of unity: Christianity. This exhibition brilliantly showcases just one example of this empire’s cultural achievements.

The Lindau Gospels with precious covers from the second half of the 9th century (front, above) and the second half of the 8th century (below).

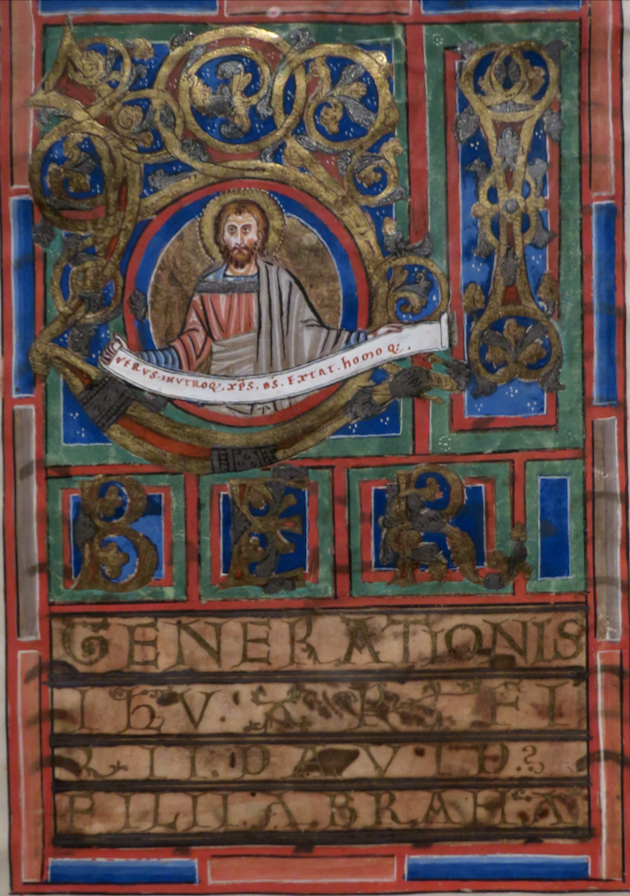

(Above) Cover of Mondsee Gospels, Regensburg, 11th Century)

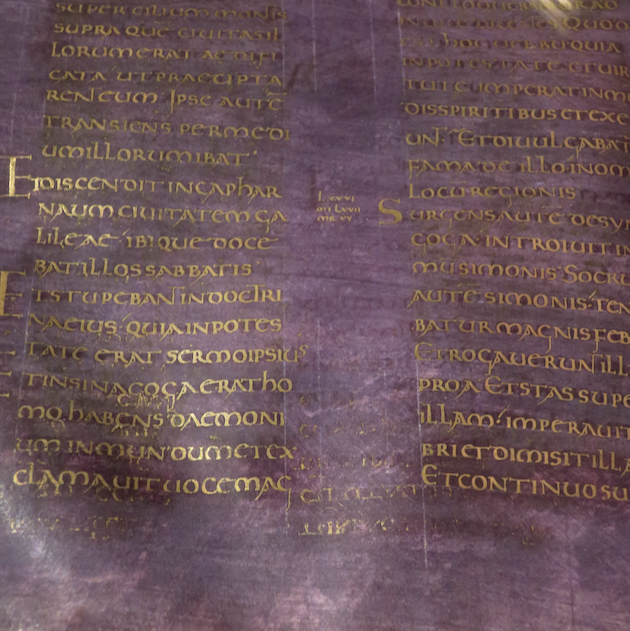

(Above) Gospels written on purple parchment wth gold ink, in imitation of late Roman work (Trier, 9th century).

(Above and below) Chalice and paten from St. Trudpert monastery, near Freiburg, Germany. (around 1230-1250)

(Above) This manuscript may have belonged to St. Hedwig of Silesia. (Early 13th Century)

(Above) Patronage by the nobility. (around 1247)

(Above) Celebration of the Mass – along with humorous animal scenes.

(Above) This illumination shows the influence of the revelations of St. Birgitta ( the Virgin Mary adoring the Christ Child Who is bathed in radiant light) (Prague, around 1405)

A new age dawns: (Above) a print from the Passion by Albrecht Dürer (Below) An illumination in the style of contemporary Nuremberg art .

Related Articles

No user responded in this post