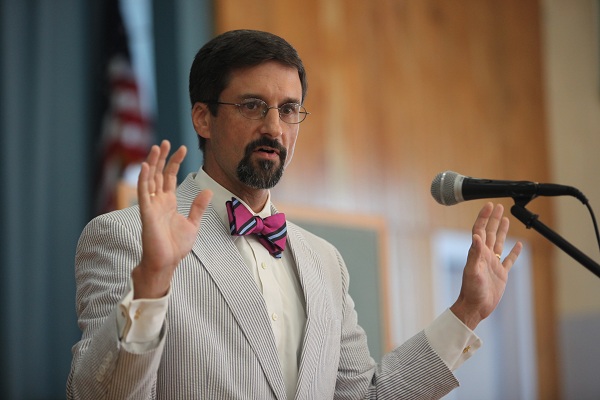

On Sunday, July 31, Professor Michael Foley of Baylor University gave a presentation on “Mystic Meanings” (in the Traditional Roman Liturgy) at St. Mary’s parish in Norwalk before a large and appreciatieve audience. Recitation of the rosary and Benediction preceded his lecture.

Fr. Greg Markey, pastor of St. Mary’s.

Richard Dobbins of our Society introduced Prof. Foley.

Prof. Foley’s presentation is given below; it is an abridgement of a much longer article in Antiphon magazine. I apologize for being unable to completely reproduce some of Prof. Foley’s graphic designs. Presentation copyright Michael P. Foley.

Mystic Meanings:

Unlocking the Secrets of the Traditional Latin Mass

By Michael P. Foley

Associate Professor of Patristics

Baylor University

Thank you. It is an honor to speak to you today, and I would especially like to thank Stuart Chessman and Richard Dobbins of the Society of St. Hugh of Cluny for inviting me, and Fr. Gregory Markey, your pastor here at St. Mary, for welcoming me. I needn’t tell you how blessed you are to have so many good people concentrated in one place doing so many wonderful things for God and His Church.

My subject today is the mystical meaning of the traditional Latin Mass or extraordinary form of the Roman rite, but in order to do so, we must first turn not to the liturgy but to the Bible. I would like to begin by presenting you a triptych of sorts. In sacred art, a triptych is a three-paneled carved or painted work chiefly used as an altar-piece. The larger central panel is the most significant, with the lateral panels usually complementing or elucidating it in some manner. The triptych as a whole, in turn, is ordered towards that which transpires in front of it: the sacrifice of the Mass. As an altar backdrop, triptychs highlight one or more facets of the divine mysteries, functioning as a window into what is happening liturgically.

The “verbal triptych” that I wish to make our backdrop today also consists of three panels consisting of three moments in the history of biblical interpretation. Once this triptych is placed upon the altar of our minds, we can then inquire into the mystical significance of the Roman rite.

A Hermeneutical Triptych

The first and central panel of our triptych is Galatians 4:22-26, the passage where St. Paul remarks:

For it is written that Abraham had two sons: the one by a bondwoman, and the other by a free woman. But he who was of the bondwoman, was born according to the flesh: but he of the free woman, was by promise. Which things are said by an allegory. For these are the two testaments. The one from mount Sina, engendering unto bondage; which is Agar: For Sina is a mountain in Arabia, which hath affinity to that Jerusalem which now is, and is in bondage with her children. But that Jerusalem, which is above, is free: which is our mother.

The meaning of the genealogy of Abraham’s sons is fairly obvious. Isaac goes on to become the father of the Jews and Ishmael, according to a later tradition at least, goes on to become the father of the Arabs. But St. Paul speaks of another level of meaning, one that is rather astonishing and by no means obvious. As sons of the “promise,” the true sons of Isaac are not the Jews but the Christians, and as sons of the “flesh” (beholden to the works of the Mosaic Law), the true sons of Ishmael are the Jews. This other level of meaning, if not contradictory to the first, is at the very least strikingly different.

Abraham

Isaac Ishmael

(promise) (flesh)

Literal, historical: Jews Arabs

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Allegorical, mystical: Christians Jews

St Paul calls this second, hidden level an “allegory,” a Greek word that means “speaking otherwise,” describing one thing under the guise of describing something else. Elsewhere in his letters Paul calls the part of the allegory that signifies something else a typos or type (which in Latin is translated as a figura or figure[1]), while St. Peter uses the word antitype (antitypos) to designate the referent, the reality referred to by the type.[2] To use St. Peter’s example, the waters of the Flood, which brought death to many but life to the eight souls in Noah’s ark, is a type for the antitype of the waters of baptism, which bring death to the old self and life in Christ Jesus, who rose on the “eighth day,” the day after the Sabbath.

Because of this New Testament terminology, the form of biblical interpretation we have been describing is variously called allegorical, typological, or figurative. It is also referred to as the “spiritual sense” of Scripture, after St. Paul’s famous line that the “letter killeth, but the spirit quickeneth” (2 Cor. 3:6), a verse that the Church Fathers understood to be a reference to this form of hermeneutics. Finally, it is sometimes called “mystical,” since the word mystical simply refers to what is hidden. However it is labeled, the fundamental idea is that there are two scripturally-derived modes of interpreting the Scripture, and that the second, more recondite mode is essential to unlocking the hidden meaning and inner unity of the two Testaments of the Bible.[3] The hidden meaning that is revealed, in turn, can be strikingly different from, though somehow still connected to, the text’s more apparent meaning.

The next panel of our triptych is from book five of St. Augustine’s Confessions, where Augustine describes his decision to move from Carthage to Rome. He is very clear about his motives at the time:

My reason for going to Rome was not the greater earnings and higher dignity promised by the friends who urged me to go… the principal and practically conclusive reason, was that I had heard that youths there pursued their studies more quietly and were kept within a stricter limit of discipline. For instance, they were not allowed to come rushing insolently and at will into the school of one who was not their own master, nor indeed to enter it at all unless he permitted.

Yet Augustine goes on to say that though this was his reason he moved to Rome, it was not God’s. Addressing his Lord he says, “It was by Your action upon me that I was moved to go to Rome” (5.8.14). He continues: “You pricked me with such goads at Carthage as drove me out of it, and You set before me certain attractions by which I might be drawn to Rome—in either case using men who loved this life of death, one set doing lunatic things, the other promising vain things: and to reform my ways You secretly used their perversity and my own.” Augustine did not know it at the time, but God wanted his to move to Rome in order to eventually meet the “bishop and devout servant of God, Ambrose” of Milan (5.13.23). Augustine writes: “All unknowing I was brought by God to him, that knowing I should be brought by him to God.” (5.13.23).

So what we see here are two levels of interpretation of an event in one man’s life.

Literal: Aug’s nexus of motives, circumstances, etc.—all intelligible on their own

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Figurative: God’s providence, taking advantage of Augustine’s freely-made decisions, calling him back to Him

What Augustine learns by the time he writes the Confessions is that life is “polysemous,” that is, that it consists of different levels of meaning, and that to unveil the enigma of one’s own autobiography, one must learn to read on a deeper, providential level. This second, providential level does not negate or contradict the first, more obvious level; indeed, there is a way in which it relies on the first level in order to meet its objectives. God, for example, did not violate Augustine’s free will and make him prefer well-behaved students to ruffians; rather, God took advantage of Augustine’s freely formed preference to bring about a providential end. The Christian notion of providence does not construe God’s presence in history as some crude deus ex machina but rather as deus in nugis—God not only in the big moments, the causes of wonderment and awe, but in the trifles, the mundane, the ordinary. The trick, then, is to learn to read even the mundane and trivial things in our lives as signs of God’s providential regard, to recognize the extraordinary in the ordinary.

This polysemous method of interpretation, which preserves the integrity of both levels while at the same time acknowledging their interdependence, elides perfectly with what Augustine also comes to learn—not coincidentally—from St. Ambrose, which is precisely allegorical or figurative exegesis. Augustine, for instance, is astonished to learn that many of the “carnal” descriptions of God in the Old Testament which he thought Catholics took literally were in fact understood by them as figures or types of divine attributes that are immaterial, or intelligible. Typology, it would appear, is essential for correctly reading both the obscure passages of the Bible and the mystery of one’s own life; it is not limited to just the Good Book.

Our third panel is taken from the first question of St. Thomas Aquinas’ Summa Theologiae, where Aquinas asks the question, “Whether in Holy Scripture a word may have several senses.”[4] His explanation as to how the Bible has more than one sense is particularly interesting. Aquinas’ basic point is that while any human author can connect “words to things” (making words point to various realities), only God can connect “things to things.” That is, only God can make one historical event or real thing act as living word or foreshadowing of another real thing, for only God sees all past, present, and future at once and can thereby “connect the dots,” making one event in history foreshadow another.

Literal words

(any author can do this) things e.g., A’s sacrifice of Isaac

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Figurative, Mystical things the Crucifixion

(only God can do)

For example, the story of Abraham’s sacrifice of Isaac (Gen. 22) has a literal integrity of its own that one could spend one’s lifetime exploring. Why does the Lord God issue such a horrific command? Why does Abraham, who is clearly concerned with justice, obey? What is poor Isaac thinking? All of these questions are worth asking, but they remain on the literal level of the text. To arrive at the allegorical, let us be attentive to the account’s seemingly insignificant details. Why is this a story about the sacrifice of an only son, promised by God, whose conception was a miracle? Why is it a three-day journey to the place of sacrifice, and why is the sacrifice a mount or hill? Why does Isaac, the sacrificial victim, carry the wood to be used for the sacrifice on his back? Why, when Isaac asks his father where the sacrificial victim is, does Abraham reply, “God Himself will provide the sacrifice”? Why, after the angel stops the sacrifice, is another victim used instead, a ram or male sheep whose head is caught in a thorn bush? From these seeming trivialities we may see emerge something awesome: the sacrifice of Isaac is an event that points forward to another event, the Crucifixion. God has used one “thing” to point another.

The Sacred Liturgy

We can now turn to what is in front of our triptych: the sacrifice of the Mass. Based on the Church’s understanding of providence, of Scripture, and of the polysemous fabric of being, it is no surprise that the source and summit of her life would come to be seen as equally fraught with allegorical significance. We see appreciation for the liturgy’s mystic meanings follow closely upon the heels of the development of the early Church’s appreciation of the Bible’s spiritual sense. Just as the most mundane details of the scriptural narrative were explored for their typological import, so too were the prayers and rubrics of the sacred rites viewed through a lens sensitive to divine polysemy and that sacramental capacity to see a world in a grain of sand.

The priest’s liturgical vestments, for example, have an easily explainable historical meaning: they were originally the street clothes of Roman citizens. The maniple was a purse or handkerchief worn on the wrist, the amice was a kind of hat, the chasuble was a sort of poncho. These historical facts correspond to their “literal” meaning. But one can also explore these garments’ spiritual significance in a way that corresponds to classical biblical exegesis. Aquinas sees at least two different kinds of spiritual meaning, one where a type points to an antitype found in the New Testament, and another where a type points to an antitype of how we should be living our lives as the adopted sons and daughters of God. Thus, every vestment worn by the priest for Mass may be seen as a type or figure of what Our Lord wore during His Passion as well as a type for the virtues in which all baptized Christians should be clothed. The maniple is evocative of the manacles by which our Lord was dragged from one place to another on Good Friday as well as a reminder, because of its proximity to the hands, for selfless service to others; the amice recalls the crown of thorns as well as the “hope of salvation” St. Paul tells us to wear as a helmet (1 Thess. 5:8); the chasuble is like the robe the soldiers mockingly put on Jesus as well as the breastplate of faith and charity mentioned by Paul in the same passage. And so on.

This is also true for the actions of the Mass. The transference of the Missal from the Epistle side of the altar to the Gospel side is redolent of the promulgation of the Gospel from the Jewish people alone to all the nations, for the “Epistle” reading in the Roman rite was sometimes from the Old Testament. When the deacon or priest reads the Gospel, he does not face East as at the Epistle but North, typologically bringing the Light of Christ to the region of coldness and darkness—for as every ancient Roman once knew and as every Texan knows today, the North is the symbol of heathenism and barbarity. At the offertory, the priest mixes water and wine in accordance with a very common dining practice of the Hebrews and other ancient peoples. However, this mixture not only reminds us of the blood and water that flowed from the side of our crucified Lord, it also figuratively recalls, however imperfectly, the hypostatic union of Christ’s two natures.[5]

As a meditation on these ceremonies indicate, the rite of the Mass is not simply a series of texts to be read and deciphered, but a living book, every jot and tittle of which puts us in touch with the living Lord. In the words of the German artist Martin Mosebach:

The Hasidic Jews, those witnesses of Europe’s last mystical movement, expressed the conviction that every word in their holy books is an angel. I want to learn to look at the rubrics of the missal in the same light: seeing every rule of the missal as an angel. A liturgical act, whose angel I have beheld, will never again run the danger of appearing as a soulless, formalistic, merely historical act that was dragged through times and ages to the point of utter senselessness.[6]

Decline of the Mystic Meaning

The last four or five centuries have not been kind to this interpretation of the liturgy.[7] This is a shame, for just as looking for the spiritual or mystical meaning in the Sacred Scriptures acts as a kind of spiritual exercise that trains the believer to read reality in all its fullness, including even the enigmatic reality of one’s own existence, so too does the activity of reading the liturgy mystically. This mystical reading is also possible in the ordinary form of the Roman rite, the Novus Ordo, but it is more difficult to do. The greater number of ceremonial options, Eucharistic prayers, and opportunities for extemporaneous variations (allowed by the recurring rubric, “in these or similar words”) makes typological exegesis of the Mass according to the 1970 Missal more arduous. When Father Bob does his Mass differently than Father Sam, even if both have good theological reasons for doing so, it gives to the laity the impression that these are mere idiosyncratic preferences, and it thus discourages them from delving into a deeper, more cosmic rationale. For the Mass to be read as a living book that points to other divinely-authored books, it should not resemble a mad lib.

Conclusion

The upshot of all this is that allegory is an essential component of Christian revelation and sensibility and must therefore remain a robust part of our Christian lives, starting with the way in which we worship. Overcoming the challenges and biases of our age would not only enrich and hone our Catholic perception of reality both inside and outside the walls of the church, delivering us from the jaded nihilism so prevalent in our world, it would work well with the goal of the Second Vatican Council and the post-conciliar pontiffs to renew the liturgy, increase biblical literacy, and rediscover the great treasures of our Latin Christian patrimony. In the words of St.-Exupéry:

And now they yawn. On the ruins of the palace, they have laid out a public square; but once the pleasure of trampling its stones with upstart arrogance has lost its zest, they begin to wonder what they are doing here…. And now, lo and behold, they fall to picturing, dimly as yet, a great house with a thousand doors, with curtains that billow on your shoulders and slumberous anterooms. Perchance they dream of a secret room, whose secrecy pervades the whole vast dwelling. Thus, though they know it not, they are pining for my father’s palace where every footstep had a meaning.”[8]

This presentation was based on a longer article on the subject, “The Mystic Meaning of the Missale Romanum,” Antiphon 13:2 (2009), pp. 103-125.

[1] Rom. 5:14; 1 Cor. 10:6, 11.

[2] 1 Pet. 3:21.

[3] Paul even faults the Jews for not having this truly revelatory method of interpretation when he says that they have a veil over their hearts (2 Cor. 3:14-15).

[4] ST I.1.10: “I answer that, the author of Holy Writ is God, in whose power it is to signify His meaning, not by words only (as man also can do), but also by things themselves. So, whereas in every other science things are signified by words, this science has the property, that the things signified by the words have themselves also a signification. Therefore that first signification whereby words signify things belongs to the first sense, the historical or literal. That signification whereby things signified by words have themselves also a signification is called the spiritual sense, which is based on the literal, and presupposes it…. Since the literal sense is that which the author intends, and since the author of Holy Writ is God, Who by one act comprehends all things by His intellect, it is not unfitting, as Augustine says (Confess. xii), if, even according to the literal sense, one word in Holy Writ should have several senses.”

[5] See the Offertory Prayer: “O God, who in creating human nature didst wonderfully dignify it, and still more wonderfully restore it, grant that, by the Mystery of this water and wine, we may be made partakers of His divinity who deigned to be made partaker of our humanity, Jesus Christ our Lord, Thy Son, Who liveth and reigneth with Thee in the unity of the Holy Ghost, God, forever and ever. Amen.”

[6] Martin Mosebach, “Was die klassiche römische Liturgie für das Gebet bedeutet,” Pro Missa Tridentina 9 (1995): 12-13, translated in David Berger, Thomas Aquinas and the Liturgy, 40.

[7] See my article “The Mystic Meaning of the Missale Romanum,” Antiphon 13:2 (2009), pp. 103-125.

[8] Citadelle, trans. Richard Howard (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1979), 19: quoted in Berger, Thomas Aquinas and the Liturgy, 40-41.

Related Articles

1 user responded in this post