Letzte Gespräche

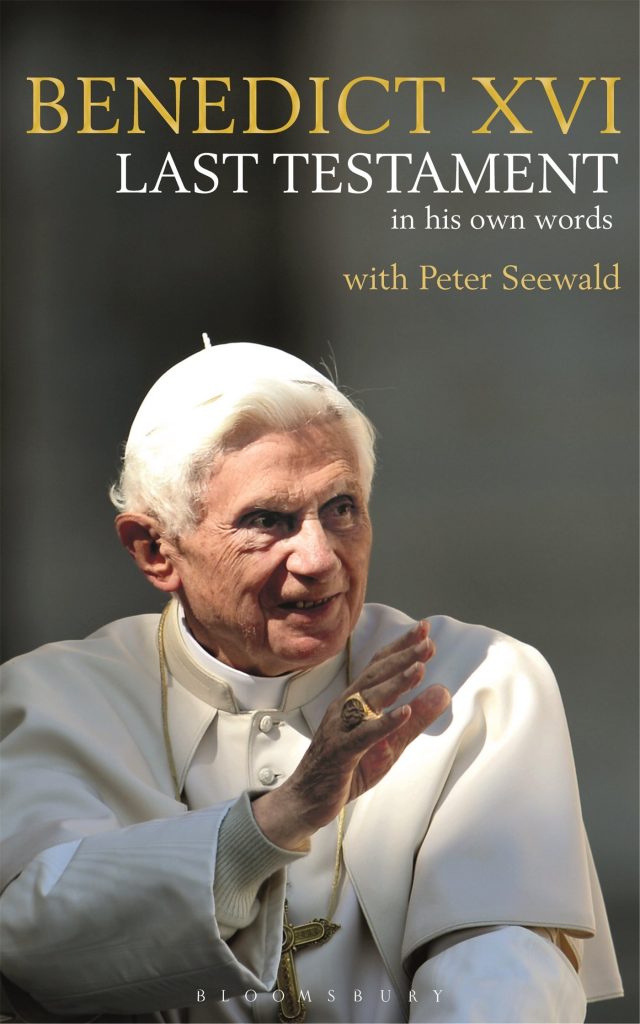

Benedict XVI (with Peter Seewald)

(Droemer Verlag, Munich 2016)

At times, given the non-stop chaotic news emanating from the Vatican, one forgets that the “Pope Emeritus” is still with us. Benedict, it seems clear now, will be remembered for two things. First, he promulgated Summorum Pontificum, in which returned the traditional liturgy to an official position within the Church. For that we – and the Society of St. Hugh of Cluny – owe him eternal gratitude. But, second, he resigned the papacy, enabling a takeover of the Vatican by the left that is plunging the Catholic Church into an ever-expanding existential crisis.

Last year, Benedict issued another book of interviews with Peter Seewald. 1) If I had access to the archival background, I would be very much surprised not to find that this book, like its 2011 predecessor Licht der Welt (Light of the World), had originated as a specific response by the Vatican to a threatening public relations issue. In 2011 it was the adverse criticism by the media (and one or more European governments?) of Benedict’s statements on condoms, his lifting of the excommunications of the FSSPX bishops and in general, his unacceptable (to the secular establishment) “conservatism.” Today, it’s the growing opposition to the policies of Pope Francis, particularly among those Catholics that were the greatest fans of Benedict

Much of what I would say about this book I had already considered writing years ago about Pope Benedict’s last interview with Seewald. Perhaps the greatest significance of this kind of book is that it appears at all. For by adopting the interview format, Benedict conforms to the requirements of Western civil society by placing himself on exactly the same level as the interviewer.2) The papal interview, introduced by John Paul II, has been carried to its ultimate extreme by Pope Francis. Indeed, for Bergoglio the allegedly impromptu interview has become a key vehicle for initiating and accompanying revolutionary change in the Church – while signaling his complete conformity with the ideology of the Western secular establishment.

Our conclusion, that a book like this illustrates the relative superiority of media power vis-a-vis the Catholic hierarchy, is further reinforced by the rhetorical style of the two partners in this “conversation.” Seewald is self-assured, even forceful, often conducting a dialogue with himself and drawing his own conclusions, which he then proposes to Benedict for comment and approval. The voice of Benedict, on the other hand, is colorless, dry and often monosyllabic. Except for certain instances we will discuss below, his style is emotionless and bald.

This is not at all to say that Seewald is an intelligent, insightful, forceful interviewer. Far from it! His entire view of the world – and all the questions he poses to Benedict – seem derived from the reading of German newspapers and magazines. All too often his tone is now fawning, now pretentious. He frequently concentrates on trivia – like what make of car Ratzinger was driving on a certain occasion. But to give the devil his due, Seewald here and there does raise certain obvious and uncomfortable issues with Benedict – but usually does not try hard enough to probe beneath the bland responses of his papal interviewee.

Now the main message of Last Conversations is simple: There are no issues, conflicts or rivalries – at least not within the Vatican. All decisions Benedict has taken have been correct. Does Benedict regret, for example, even for a minute, his own resignation? “No, no, no. I see every day, that it was right.” Did he resign under the pressure of intrigues and adverse events? Certainly not – everything was in order when resigned. Seewald: “Was there an aspect (of the resignation) that you perhaps had not considered – that only afterwards has become clear to you?” “No.” The gay lobby within the Vatican? Only a small group which Benedict already had neutralized by the end of his pontificate. Vatileaks? All the fault of one rogue butler!

Pope Francis? According to Benedict, he has such a straightforward way with people; his apostolic exhortation Evangelii Gaudium and his interviews show he is a “thoughtful man.” Seewald: ”So you don’t see anywhere a rupture with your pontificate?” “No. … Naturally, there are perhaps new accents but no contradictions.” And is Benedict satisfied with the papacy of Pope Francis so far? “Yes. A new freshness in the Church, a new happiness, a new charisma that appeals to people – that is already something beautiful.”

And so on and so forth. It doesn’t make for compelling reading – and often seems to conflict with known facts and the statements of highly placed individuals (such as Pope Francis). In this respect, isn’t this book a continuation of the mainstream “narrative” of the post-conciliar Roman Catholic hierarchy, as refined during the years of John Paul II? The clergy labor to project the outward appearance of omniscience, unity and infallibility, while problems are denied or swept under the rug. This style of public relations management, moreover, is very similar to that of present–day government bureaucracies and business corporations. Before 2007-2008, didn’t our finance industry swear all was in order and proceeding according to plan – and then the bankruptcies and takeovers were announced. For the difficulty is what perhaps starts as a tactic to manage the perceptions of the public, employees and other institutions inevitably becomes an article of faith of the manipulators themselves. In Church, business and government the inevitable outcome is growing disassociation of the leadership class from reality.

The earlier Ratzinger of the 1980’s did acknowledge a crisis – at least liturgically. His Ratzinger Report was a precious spotlight on the liturgical disaster of the Church – a disaster that was otherwise denied by the entire establishment. Later, regrettably, Ratzinger seems to have felt compelled to resume the role of the company man, the ecclesiastical bureaucrat.

At times the inability of the team of Pope Benedict and Seewald to focus on the issues produces real stylistic gems:

Seewald: “That means that you didn’t receive in advance the first apostolic Exhortation of Pope Francis, Evangelii Gaudium?”

Benedict: “No. But he sent me with it a very nice personal letter in his tiny handwriting. That is much smaller than mine. Compared with him, I write really large.”

The Pope Emeritus maintains a remote and serene air. One would get the impression that Benedict had been a distant observer, rather than a direct participant, in the often-tumultuous events of his pontificate. A failure to get one scholar to endorse his candidacy for a professorial position in 1955 perturbs him more than the breakdown of the Church. It’s left to the troops on the ground – the families and a minority of the parish priests – to deal with and “get excited about” the closing of parishes and schools, the wave of clerical scandals, the alienation of the next generation and most of their contemporaries from the faith.

Now Pope Benedict is primarily a scholar, you say, not a man of action. In the case of a man with such a distinguished academic career and over thirty years of experience at the highest levels of the Vatican, one would look forward to perceptive reflections and judgments on the Church, the world and our age. But you will be very disappointed – there are precious few of them in this book. We might also expect from Benedict, who has demonstrated such eloquence on things of the spirit, spiritual insights as well. These are limited to a few pages – and sometimes cry out for further development, given the present situation of the Church:

“If a pope only received applause, he would have to ask himself if he was doing something wrong. …There will always be contradiction and the pope will always be a sign of contradiction.”

Readers may be surprised to find that at least half of Last Conversations is devoted to a miniature biography of Ratzinger leading up to his election as Pope. I frankly found little of interest here – but there are compensations. In the discussion of Vatican II, for example, Benedict entertains the question of whether the council was worth it, before of course reaffirming it was the right thing to do. Then there is an appreciation of German scholars who offered the first resistance to the chaos enfolding the Church after the Council, names that Catholics should better remember today: Hubert Jedin, Paul Hacker. But in the case of Hacker, the contacts chilled when he started to criticize the Council. And as for the “other side?” Benedict does exhibit a decidedly cool attitude towards Rahner and Kueng. In contrast, he finds Johann Baptist Metz to have been a true son of the Church. And what who was largely responsible for the post-conciliar crisis? “Journalists!”

Pope Ratzinger does not totally preserve his calm in this book. He has some unexpectedly harsh words for the German Church that so consistently opposed him during his pontificate. But, I submit, to attribute all the problems there to the Church tax and the bureaucratic mentality of clerical and lay functionaries does not tell the whole story.

And what of the topic that probably interests our readers most – the liturgy? As to the “reform of the reform,” Seewald frankly asks why so little happened in the realm of the liturgy – where Benedict had full authority.

“You can’t do that much institutionally and legally. The important thing is that men learn inwardly what liturgy is and what it really means. That‘s why I have written books.”

Benedict even denies that the few steps he did take – such as introducing communion on the tongue at papal masses – had any policy significance beyond the merely practical. But, Seewald asks: couldn’t you just have spoken an “authoritative word?” Benedict’s succinct answer: “No!” Is it surprising, therefore, that ROTR went nowhere under Benedict?

In the case of Summorum Pontificum, however, the Pope Emeritus miraculously gives a clear and convincing restatement of its rationale:

(It was not at all a concession to the FSSPX) “It was important for me that the Church herself be inwardly at peace with her own past. So that that, which once had been sacred, is not now wrong. …(M)y intention, as I have said, was not tactical – for me it was a matter of the substantive issue itself.”

Of course, the currently reigning bishop of Rome has expressly contradicted this only a few weeks ago.

Last Conversations reveals that the personality of Joseph Ratzinger was indeed very ill-suited to an office requiring the capacity to lead, manage and rule. That is even truer in the chaos of a post-conciliar Church led by incompetent, rebellious and often treacherous clerics and in the sights of an increasingly hostile modernity.

But the failure of his pontificate is not at all just the story of a well-meaning man who lacked leadership skills or (as he says in this book) the “ability to judge people.” It is the institutional failure of a Vatican and a hierarchy increasingly remote from reality and, sensing their own weakness, avoiding confrontation with both the secular world and contrary movements within the Church itself. It is a tragedy that Ratzinger’s many valid insights and initiatives for a reform of the Church clashed so greatly with this clerical culture of which he himself was so much a part.

In retrospect, we should not have been surprised that the outcome of this conflict was capitulation (Benedict’s resignation) and the ascendancy of a diametrically opposed movement. But Benedict has left to us his one great achievement, his true “last testament” – Summorum Pontificum. And to evaluate its effects will take more than a slim book of interviews. Only future generations will know the end of the story.

- This review is based on the original text and all the quotations are my own translations. I think that’s probably fortunate – given that the ( I hope inappropriate) title Last Testament: in His Own Words has been bestowed on the translation.

- As the late Thomas Molnar noted when John Paul II initiated this practice.

Related Articles

No user responded in this post