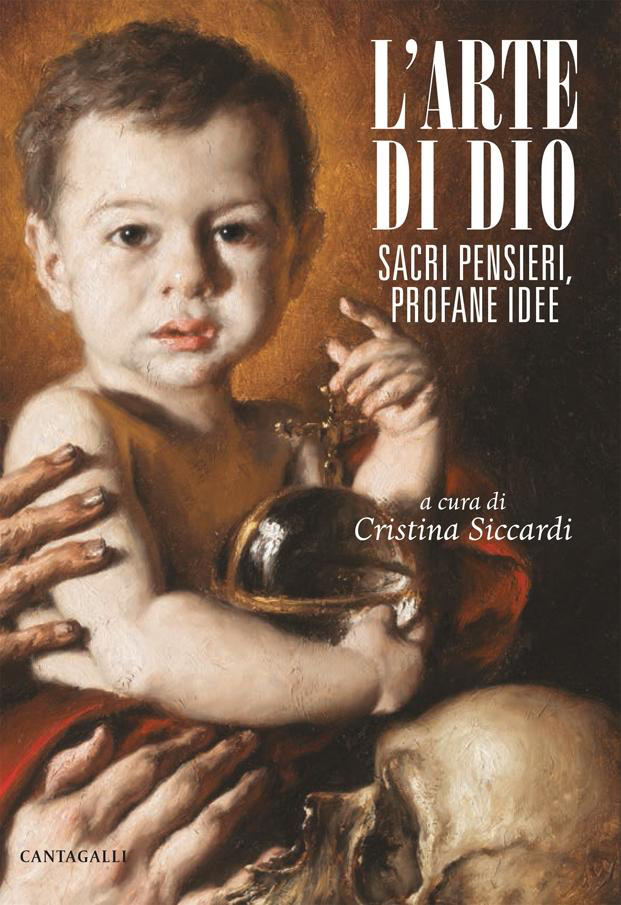

L’Arte di Dio: Sacri Pensieri, Profane Idee

Edited by Cristina Siccardi

(2017 Edizioni Cantagalli S.r.I., Siena)

Art and Religion, Beauty and the Sacred: topics that have received ever-increasing attention among Catholic Traditionalists as their movement matures and, moving beyond the mere survival of the liturgy, addresses fundamental issues of our culture. In general, Traditionalists now understand that some necessary connection exists between the realms of the sacred and beautiful. Again, generally speaking, Traditionalists tend to look for their models for a successful interaction of the two spheres in the historic styles and masterpieces of the past.

This is in stark contrast to the policy of the Church establishment, which usually takes one of two forms. More prevalent on these shores is aggressive hostility towards “mere aesthetics” in liturgy, art and music, while instead promoting anti-artistic tendencies like those of evangelical Protestantism. Alternatively, one encounters, especially in Europe, the direct importation of contemporary “elitist” artistic trends into the Church. To the extent new churches are built at all, for example, their architecture usually is informed by a modernist ethos. Cardinal Ravasi may serve as the “patron saint” of this approach. There are and have been laudable exceptions to these dominating tendencies, but as a whole the institutional “Conciliar” Church tends to dispense with the idea of the “beautiful” as a criterion of ecclesiastical art.

The fossilized continuity of institutional Catholic Modernism. (Above) Church of the Epiphany, New York (1967). (Below) The chapel of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary, New York (2009). (2nd below) The chapel of the NYU Catholic Center (2012)

Yet are there not clear historical precedents for the experience of the beautiful leading to religious conversion and renewal? Did not Prince Vladimir of Kiev convert to Eastern Orthodoxy after his emissaries had encountered the magnificence of Hagia Sophia and its grand liturgical ceremonies? Vladimir Soloviev in turn used this example to defend François-René de Chateaubriand’s Genius of Christianity (1802), which argued the case for Christianity based on religion’s role in creating Western art and culture. Also in the early 19th century, the first generation of German romantics rediscovered the art, architecture and literature of the Middle Ages. Many of these writers progressed from an appreciation of Gothic art to an understanding of the Catholic religion, resulting in a series of prominent conversions. The German Romantic Movement in no small degree laid the foundation of the spiritual revival of German Catholicism.

To address this complex of issues in the contemporary Church, Cristina Siccardi has assembled a most distinguished group of contributors: writers, artists, performers, historians, museum administrators and theologians. Here are both theoreticians and hands-on creators of art. Not a few have a distinguished place in Italian culture; some, like Martin Mosebach and Roberto de Mattei, should be already well known to readers “over here.” The contributors are both secular and Catholic and not everyone speaks with the same accent – but that’s only as it should be! What unites them all is their engagement for art, the sacred and the beautiful – and their opposition to the destruction or at least deterioration of these values in modernity and in the modern Church.

Each contribution takes the form of an interview and discussion with Cristina Siccardi; in addition, there is a good-sized appendix with important, previously published pieces from people like Jean Clair and Fr. Uwe Michael Lang. There’s also a set of illustrations that serve to highlight the contrasts between “traditional” (in a range of styles) and modern ecclesiastical art – a picture is worth a thousand words.

It’s hardly possible for me to summarize the riches to be found in this book. Among the many noteworthy contributions, let me single out a few to give you an idea of the contents:

In her introduction, Cristina Siccardi writes of the disaster of ecclesiastical art in Italy today – the product of Vatican II. “Is it possible in sacred art that the good can be expressed by the anti-aesthetic? Since the second Vatican Council this has become possible.” To the extent churches are built at all, they are iconoclastic spaces conceived with the express intent of breaking with the past. Historic buildings, on the other hand are increasingly reduced to museums – like Castel Gandolfo under Pope Francis or the convent of St. Mark in Florence. Even those cathedrals, churches and monasteries that still have clergy and can function as places of worship usually welcome mostly tourists today.

Christina Sourgins give an admirable summary of the critique of “contemporary art” that has been developed largely by French authors. She exposes the government-subsidized and art market-oriented fakery of “performances” and “installations.” But what is far worse is that this “art” has all too frequently found a home in churches and cathedrals. Deliberately blasphemous and provocative, these works contradict the form and purpose of the magnificent spaces that surround them. “Contemporary art acts as the contrary of the gospel: honor to him through whom scandal comes!” To dialogue with such art leads Christians only to a “quiet apostasy.”

Martin Mosebach writes of the “attack on the Catholic rite.” Mosebach emphasizes that although the ancient rite has generated an incredible quantity of art, music, painting architecture and sculpture, these are not its essence, which is independent of these great cultural treasures. Rather, the main element of its beauty is the form of the rite itself. Any celebration of the Traditional mass, even in the most wretched of chapels, has an incomparable beauty – the rite itself “creates its own space.” “The splendid art of the most beautiful churches has absolutely no value if it cannot enter into direct correspondence with the rite for which it was created.”

Mosebach: The primary beauty of the Mass is the rite itself, not the embellishments (architecture, vestments, music etc.) with which it may be surrounded. (Above) Easter liturgy in the tiny one room Russian Catholic chapel of St Michael, New York). (Below) A Missa Cantata celebrated in the basement church of St Mary’s Greenwich before a small congregation of young people.

But through art man gives greater glory to God. (Above) A solemn Requiem Mass celebrated recently in the church of St. Vincent Ferrer, New York. (Below) Cardinal Burke celebrates Mass in the Karlskirche, Vienna.

Andrea de Meo Arbore develops intriguing ideas regarding architectural archetypes that are or should be constitutive of a Catholic Church such as the tower, the monumental portal and the dome. Citing medieval theorists such as Durandus, de Meo Arbore finds that each of these elements articulates a semantics that refers to the spiritual world. “Thus, the cupola may be the symbol of heaven or of the pregnant womb of Mary.” Vittorio Sgarbi in a similar vein writes that post-sixties church architecture lacks the cupola and the vault: the cupola is heaven and the vault is the dimension which stands above men’s’ heads. The lack of architectural forms like the verticality of the Gothic or the cupola and vaulting of the Renaissance eliminates their symbolism – equivalent to a “renunciation of heaven.”

A specific cause of dismay mentioned by several contributors (like Vittorio Sgarbi) is the ” liturgical adaptation” of churches and cathedrals to the new mass in Italy resulting in the gutting of sanctuaries (chancels) and the elimination of altar rails, altars and pulpits. Antonio Natali states “what … has happened in our churches to adapt the architecture of the past to the new liturgy doesn’t have even the shadow of a cultural justification.” In this regard, Pietro de Marco writes of modernity’s specific horror of the baroque, the fascination with the allegedly “pure” and of the destructive force and anti-baroque vandalism that succeeded the Council.

(Above and below) Vandalism in the sanctuary – the baptismal “swimming pool” installed before the former high altar of the Jesuit church of St Francis Xavier, New York.

(Above and below) Jesuits again: “Liturgical adaptation” in the sanctuary of the Jesuit church of Vienna.

This book represents an exhaustive compendium of opinion and commentary on truth, beauty and art in the Church and the world. Appropriately enough for (using the term broadly) traditionalists, the various contributors identify and clarify issues and problems but do not necessarily offer “solutions” or role models. But L’Arte di Dio is an indispensable resource for anyone concerned with questions of the liturgy and ecclesiastical art. The book has its own website; we would welcome the day when it is translated into other languages.

Related Articles

1 user responded in this post