Paris is one of the grand cities of late Western civilization – entirely taken up with business, shopping, eating, beauty care, tourism, etc. But as a sombre counterpoint to all this relentless activity are the funerary monuments of the 19th century. Now located in very commercial districts but entirely off the touristic beaten path, they commemorate the victims of the disasters, crimes and misfortunes of the past. Like the tall clock in the last black velvet room in The Masque of the Red Death, they serve as a stark memento mori to the revelers outside, lost in the frenzy of modernity. They also bear witness to the once strong Catholic faith of France – even amid the secularizing society of the 19th century. A fortunate “break in the action” on a recent business trip gave me the opportunity to revisit these memorials.

Not too far from the Gare Saint-Lazare is the Chapelle Expiatoire, the oldest and largest of the chapels we will consider. It commemorates the spot where the bodies of Marie Antoinette and Louis XVI were found after the restoration of the monarchy in 1815. After their execution by the Revolutionary government, their bodies had been unceremoniously deposited in the cemetery of the Madeleine which soon received so many more victims as the terror progressed. The chapel was erected by Louis XVIII, the first king of the restoration and finished in 1826 by his successor, Charles X. Like the other chapels we will visit, the Chapelle Expiatoire is a cenotaph – King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette were reburied in the basilica of Saint Denis.

Once located in a romantic park, the chapel is now surrounded by 19th century commercial buildings. An entrance pavilion leads to an open walkway flanked by unmarked graves on either side – commemorating the Swiss guards of the king massacred in 1792. They now stand eternal watch before what had been the resting place of their king. The domed chapel itself is a severe yet brightly lit neoclassical space. The decoration of the ceilings and floor is simple and elegant: that is also true of the sanctuary which unfortunately is no longer in regular use. In the side apses are statues of King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette consoled by Faith and an angel.

Marie Antoinette was originally scheduled to be guillotined between two prostitutes….

In a dark passage beneath the chapel is a starkly simple altar marking the spot where the royal bodies were found. One thinks of the many other victims dumped in this cemetery whose bodies may not have been exhumed. Returning to the surface, a visitor can explore arched aisles that flank the chapel grounds. These passages, sheltered from the noise of the traffic outside, inspire one to reflect once more on the many early, forgotten victims of the birth of modernity who were or still are interred here.

In the 19th century the Chapelle Expiatoire was threatened again and again by revolutionaries, Communards and freemasons. The altar has not been used regularly since the !880’s. By 1914 the ideological threats had abated, and the chapel has survived until our time, if only as a “national monument.” But each year a memorial mass is still celebrated on the day of Louis XVI’s death, January 21.

The Chapelle Notre Dame de Compassion sits in a small park – a kind of traffic island – not too far from Porte Maillot. Near here, in 1842, Prince Ferdinand-Philippe, heir to the French throne, fell out of his coach when the horses reared. He died in a nearby house. It was a catastrophe for the Orleans monarchy, which had been pursuing a dubious “middle way” between Christian monarchy and 19thcentury capitalism.

King Louis-Philippe and Queen Marie-Amélie had a chapel constructed on the location of his death. Completed in 1843, it has remained near this site ever since. I say remained, because in the 1970 it was moved, stone-by-stone, a few hundred yards to accommodate the construction of the monstrous Palais des Congres.

The architecture, in a Byzantine style, makes a dark, mysterious impression. Inside, the sombre effect is reinforced by the exposed stonework and the black and white of the floor and altar. Yet this small chapel has some remarkable works of art. A marble sculpture by Triqueti shows Prince Ferdinand-Philippe at the moment of death. Above is a praying angel, sculpted by Ferdinand-Philippe’s sister, Marie d’Orléans, one of the first female sculptors in Europe. Triqueti also created the expressive Pieta above the altar with the features of the prince and his mother.

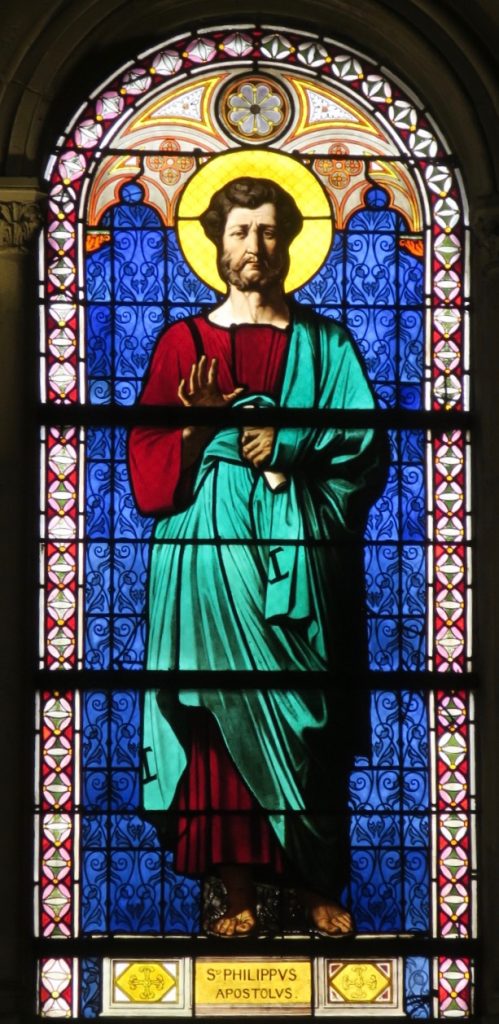

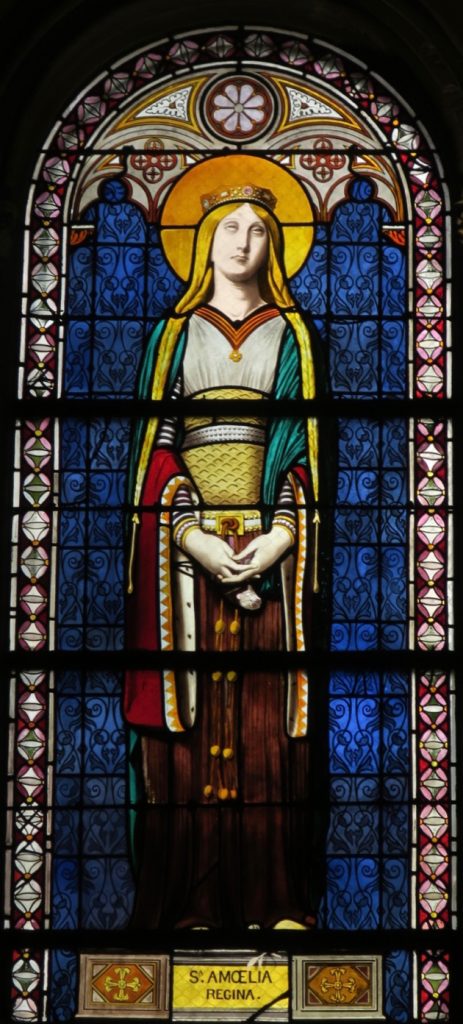

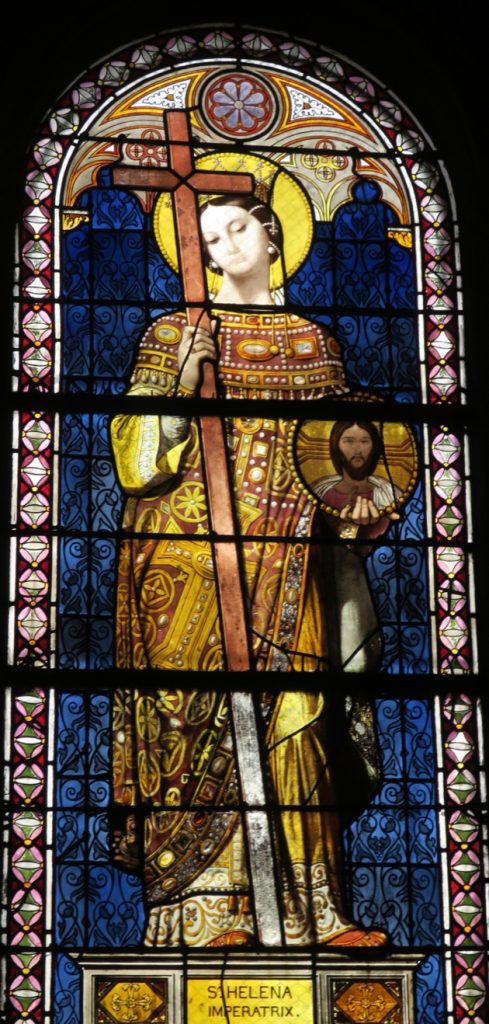

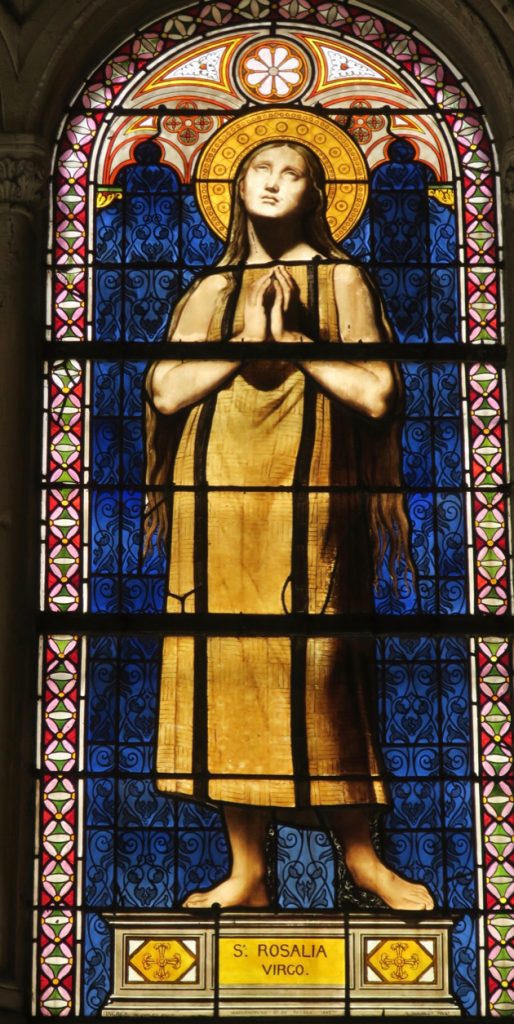

But the chapel’s real treasure is the set of the stained-glass windows, made to the designs of Ingres. They depict the theological virtues and saints associated with the reigning French royal family. The obscure interior displays them to great advantage. Close inspection reveals that St. Philip has the features of Louis-Philippe, Saint Amalia those of the Queen and that St. Ferdinand is a portrait of the defunct prince. Perhaps we look askance such practices nowadays! But Ingres – a partisan of King Louis-Philippe – left here a remarkable achievement in a medium not normally associated with his neoclassical style. And the chapel itself, combining in its architecture and decoration Byzantine, neoclassical, Romanesque and realistic elements is a remarkable artistic success.

In contrast to the Chapelle Expiatoire, Notre Dame de Compassion remains an active church; indeed, in 1993 it was elevated to a parish. There are usually one or two women at prayer; fresh flowers are placed before the altar. Are they a legacy from the dwindling ranks of the French monarchists? Or is this silent, obscure interior – commemorating a tragedy of so many years ago – especially conducive to prayer by those beset by the sorrows of a deaf and unforgiving world?

The Chapelle Notre Dame de Consolation, located a couple of blocks from the heart of the luxury shopping district of Paris, is the memorial of a horrific tragedy in 1897. The Bazar de la Charité was an annual fundraising event sponsored by Catholic aristocrats. In 1897, the lavish pavilion featured a recent invention: a movie projector. But, powered by very flammable oil, it exploded when the fair was full of visitors. Within minutes the bazaar was a mass of flame. Women ran out with their elaborate hats of the fashion of that day aflame; others were burned alive or trampled to death in the crush. When it was over some 126 people – mostly Catholic, mostly women and children, were dead. This tragedy left its mark in the literature of the time: Joris-Karl Huysmans and Leon Bloy – the latter in a singularly unpleasant commentary – make reference to it. Now and then it returns to the public eye. The New York Times wrote about it some ten years ago and a French television channel is supposed to air a presentation on the Bazar de la Charité this year.

The families of the victims purchased the fairgrounds where the tragedy occurred and funded the construction of the chapel, completed in 1900. It is a lavish affair, reproducing in Paris a 17thcentury Roman baroque church. The interior overflows with marble and statuary, gleaming metalwork and paintings. Above, in the cupola, the Virgin points out to the victims the path leading to Paradise.

At the rear of the church is a “cloister” with beautiful silver stations of the cross. Set among the solemn halls are sculptures and cenotaphs commemorating the dead. A marble copy of a famous image of the dead Christ in Naples was donated by an American woman who had escaped the flames. An elegant cenotaph honors the memory of the most prominent victim: Sophie Charlotte of Bavaria, the Duchesse D’ Alencon. She was the sister of the famous Sissi – the wife of Emperor Franz Joseph – and herself once had been betrothed to King Ludwig II of Bavaria. The most poignant memorial, however, is a case holding personal items rescued from the inferno: rosaries and prayer books belonging to the victims as well as two charred dolls….

Despite all the splendor, Notre Dame de Consolation is a somber memorial, quiet and mysterious. Yet it is also full of life. Because the chapel still belongs to the association of the descendants of the victims, it is outside the jurisdiction at the Archdiocese of Paris. Not long ago the association entrusted the chapel to the FSSPX. At mass times the chapel is full again. indeed, Notre Dame de Consolation today boasts an amenity not commonly needed in the Catholic churches of France: a cry-room! So, this domain of the dead has returned to full life, both liturgically and physically. I am sure the victims of that long-ago disaster are pleased!

Related Articles

2 users responded in this post