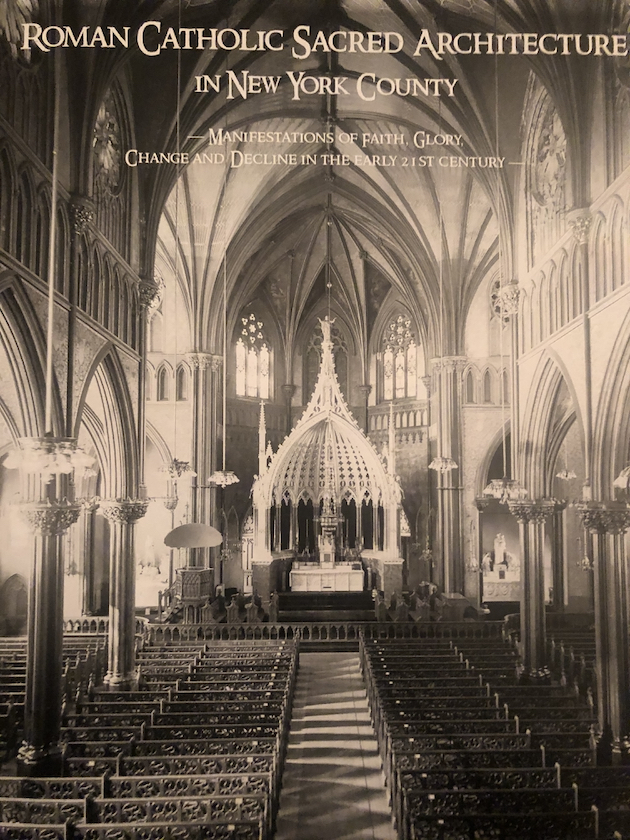

Roman Catholic Sacred Architecture in New York County: Manifestations of Faith, Glory, Change and Decline in the Early 21st Century

By Paul R. Peters

2020

As our readers probably know, we have long been following the history of the Catholic churches of New York City. Recently I was fortunate to receive and read the work of another researcher in the same area. Paul R. Peters has written and self-published Roman Catholic Sacred Architecture in New York County: Manifestations of Faith, Glory, Change and Decline in the Early 21st Century (2020). In it, he covers the great majority of the Catholic parish churches of Manhattan island. (Non-New Yorkers need to know that New York County is synonymous with Manhattan plus Marble Hill in the Bronx.)

Peter’s book is one of select few on this subject. Thomas J. Shelley’s Bicentennial History of the Archdiocese of New York of course also covers all the parishes of Manhattan. Then, there is Rene S. James’ The Roman Catholic Churches of Manhattan (2007, also self-published). Finally, the grandfather of all such studies – and still the best – is John Gilmary Shea’s 1878 book on New York City Catholic churches. In Sacred Architecture Peters gives us several photographs and a brief description of each of the churches in New York. Many of the photographs are his own, taken from 2003 onwards, but he has supplemented these with well-chosen examples from local archives or from other sources. See, for example, this book’s beautiful cover photograph of the interior of the now-closed All Saints parish in Harlem, taken when that church was relatively new. Another example is the striking image of the interior of Old St. Patrick’s Cathedral.

Our author has put together this book with a specific purpose in mind. Peters documents through photographs the status, before and after the Council, of each of these churches. This focuses, in particular, on the chancel or sanctuary of each church and a melancholy review of the damage that was done after the Council. In most cases this involved moving the altar forward, eliminating or reducing the communion rail, and placing a new altar at the center of the church on a platform projecting into the nave (what Peters calls a “build-out.”) It also usually was accompanied by the gross simplification or outright destruction of the former decorative program of the church which so often had featured gothic altars, stencils, paintings and statuary. Peters is rightfully indignant at this desecration, carried out supposedly to “break down barriers” between the celebration of the Mass and the people. They of course largely departed, which is why parish after parish after parish is closing. This book is a visual chronicle of the devastation.

Those churches were indeed fortunate where the post-Conciliar updating was limited to placing a table between the grand high altar and the communion rail, leaving all else intact. New York, however, has the good luck to have more than handful of these, in which the Conciliar wave of destruction of art was halted by the parish’s poverty or the resistance of the donors’ families.

Peters’ book obviously has great appeal for the connoisseur of New York churches. He has here pictures of the interiors of churches with which I was familiar but never got around to photographing before their destruction – such as St. Ann’s or the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary. I should especially emphasize his discussion of the once glorious Church of Saint Thomas in Harlem – an equally colorful and wildly decorated counterpart to Our Lady of Good Counsel. It was shut down and destroyed by Cardinal Egan. Our author also has located intriguing photographs of the original 19th century churches of the parishes like St. Andrew and Immaculate Conception which later acquired grand new buildings.

To describe some 100 churches and their constantly changing appearance is a formidable task – I appreciate the magnitude of the effort and don’t want to seem critical. For a second edition, however, I would suggest more systematically providing, where possible, dates for the photographs and for the narrative. For as the author himself tells us, it is not so simple as “before the Council” and “after the Council.” In some parishes, ( e.g. St. Stephen’s, St. Agnes) major changes – and in some cases major damage – was done prior to the Council. In other cases, post-Conciliar ravages have been partially repaired (Our Lady of Pompeii, Our Lady of Sorrows).

Despite the vast terrain Peters covers, I have only been able to identify a very few instances where he is outright wrong – such as his description of the combination of the parishes of St. Emeric and St. Bridget (Brigid). But even there we are grateful to him for pointing out the dedication (in fact at St. Emeric, not St. Brigid) of a chapel to Cardinal Egan (while he was still alive)! This book’s list of churches may be comprehensive but it is not exhaustive – one prominent church missing is the shrine of St. Frances Cabrini in Washington Heights. I would also dissent from the author’s aesthetic judgment in certain cases (like the renovation of St. Francis Xavier church).

All in all this is a great book for enthusiasts of ecclesiastical architecture or New York City history. And also a sobering work for those Traditionalists who want to experience the bitter feeling of seeing the details of so much that has been senselessly destroyed. Highly recommended!

Related Articles

1 user responded in this post