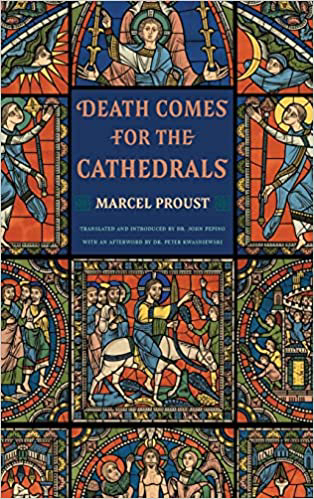

By Marcel Proust

Translated and introduced by John Pepino

Afterword by Peter Kwasniewski

2021 Wiseblood Books, Milwaukee, WI

In 1904 the Catholic Church in France faced the imminent loss of all her possessions. The churches were to be nationalized by a state controlled by atheists and the Masonic lodge; subsequently their conversion to secular use was entertained. Ultimately, however, the continued use of the church buildings by the Catholic Church was conceded. It was in the midst of this crisis that Proust wrote the essay Death comes to the Cathedrals.

Proust makes some elementary aesthetic and historical points. The cathedrals do not merely serve as a utilitarian facility to house the gathering of a congregation, but are a symbolic restatement of the Christian faith. Building on the work of contemporary scholars and writers such as Émile Mâle, Proust writes of how each seemingly insignificant detail in a cathedral is laden with symbolic meaning. And this all relates back to the rite celebrated in the cathedral: the (traditional) Catholic Mass. For Christian worship to cease in the cathedrals would deprive them of meaning – to leave these buildings empty shells. A museum is not a living thing. In Paris just look at the Pantheon or “Napoleon’s Tomb” to see the sad results of alienating Catholic churches from the purpose for which they were created. As Proust writes:

Today there is not one socialist with taste who doesn’t deplore the mutilations the (French) Revolution visited upon our cathedrals: so many shattered statues and stained-glass windows! Well: better to ransack a church than decommission it. As mutilated as a church may be, so long as the mass is celebrated there, it retains at least some life. Once a church is decommissioned it dies, and though as an historical monument it may be protected from scandalous uses, it is no more than a museum.

…

When the sacrifice of Christ’s flesh and blood, the sacrifice of the Mass is no longer celebrated in our churches, they will have no life left in them. Catholic liturgy and the architecture and sculpture of our cathedrals form a whole for they stem from the same symbolism. 1)

Such a loss is not just a private Catholic matter but should be a concern for all humanity – but especially for the French nation. For the great series of cathedrals, beginning with the basilica of St. Denis and culminating in the extraordinary but unachieved (and unachievable) Beauvais, is the chief glory of French – and even of world architecture. What Proust is suggesting – and what French traditionalists – both Catholic and non-Catholic – have insisted upon ever since is that Catholicism is so integral to the French national identity that any attempt to purge it strikes a blow at the nation itself. Just look at the recent statements of Eric Zemmour – a secular Jew – for a passionate (re)presentation of these principles. Contrary to the views of Catholics influenced by Vatican II, liberalism and ultramontanism, this bond between the Catholic faith and the nation is not weakness, but strength! Just look at the Poland in the last century for a similar example.

Peter Kwasniewski contributes an afterword linking the events in France in Proust’s day to those of our own time. He tells of his own enthusiasm on first encountering Chartres. Then he compares the ritual vandalism after Vatican II with the measures of the Freemasons of the Third Republic. Today the Church herself largely accomplished what the anticlerical politicians of yore stopped short of achieving – the expulsion of the Roman Catholic rite from the architectural masterpieces to which it had given life. Indeed, these great cathedrals began to be viewed as aberrations from what should be the new Catholic architectural norm: some kind of utilitarian shed. In the cathedrals themselves the clergy place puny blocks in the transepts on which to celebrate their new form of liturgy.

Under such circumstances, Catholics can only be grateful for the de jure or de facto state control of church buildings in France, but also in Italy and Germany. Otherwise a wave of destruction – like that which swept over the sanctuaries of most churches in the United States – would have done irremediable damage to the far more significant artistic heritage of Europe.

And this struggle continues to the present day. After the highly symbolic destruction of the roof of Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris a conflict has broken out between the archdiocese of Paris and scholars, artists and preservationists. For the archdiocese wants to adapt parts of the restored cathedral to a new didactic plan to make the Catholic faith “comprehensible” to the visitor, using in part projected images.

The journey continues past 14 side chapels of the cathedral. Those existing chapels, … are to be reconfigured so as to “create a fecund dialogue between contemporary creation and the church.” Each is to receive a yet-to-be-created work of art, which is to be juxtaposed with a historic work, such as a painting or stained-glass window, while a text is projected onto the wall. These chapels are hardly the 14 traditional Stations of the Cross, the sequence of the Passion that culminates with Jesus being laid in the tomb. Here the 14th chapel is to be dedicated to the theme of “reconciled creation,” a phrase taken from Pope Francis’s encyclical “Laudato Si’,” which addressed environmentalism and climate change .2)

Pope Francis and environmentalism, not God, thus become the focus of this media presentation – which in any case has a didactic message utterly foreign to that conveyed by the Gothic architecture of Notre Dame itself. But are the bright lights and television screens, the souvenir machines and explanatory placards in St Patrick’s Cathedral in New York any better? (At least here though, offending modernist statues and altars have been removed and an attempt has been made to restore the stylistic harmony of the chancel and the side altars of the nave).

Speaking of St Patrick’s, the St. Hugh of Cluny Society has always tried to advance the unity of architecture, liturgy and music primarily in the greater New York Area. Of course, not even New York’s great church of St. Vincent Ferrer matches its European models – let alone our small Victorian neo-gothic parish churches. But the Catholic Church in America once had a vision of reproducing on these shores masterpieces of Catholic architecture – as a means for promoting and celebrating the faith. That is why we work for their preservation. And when in any such church the Traditional liturgy is celebrated with full ceremony and fitting music one gets a glimpse of the real meaning of all the elements of art and of the faith working together. Some (like Cardinal Dolan) may mock such old churches as “museums” but, as Proust so eloquently points out, a Catholic church celebrating the traditional Mass is the exact opposite of a museum!

I too have experienced the power of the French cathedrals. Since the 1980’s, the annual traditionalist pilgrimages between Paris and Chartres have once again filled that great cathedral with life through the presence of so many young people at the celebration of the traditional Mass. On such occasions, Chartres, as large as it is, cannot accommodate all the pilgrims!

Chartres has spires, the statues and stained glass. But it has also suffered a number of harsh unfeeling restorations and also attracts, given its easy accessibility from Paris, a relatively large number of tourists. Other cathedrals like Laon, Bourges or Beauvais – largely unrestored, silent and mostly abandoned to themselves in the midst of their semi-deserted towns – afford the visitor a more evocative impression of artistic grandeur, loss and the ravages of time.

(Above) The cattle on the towers of Laon cathedral. Proust: “We know that since the oxen of Laon had christianly drawn the construction materials for the cathedral up the hill for which it rises, the architect rewarded them by setting up their statues at the feet of the towers. You can see them to this day as, in the din of the bells and in the pooling sunlight, they raise their horned heads above the colossal holy arch towards the horizon of the French plains… .” (Below) The atmospheric old town of Laon.

Pope Francis has now launched a vast campaign to eradicate the traditional Mass, to try once again to achieve what the atheists of Proust’s day had sought to accomplish – ultimately unsucessfully. Death comes for the Cathedrals thus takes on a relevance perhaps unanticipated when this book’s introduction and afterword were written. And in addition to the religiously motivated Traditionalists, just as in Proust’s day, defenders of our common artistic heritage once again have risen up to defend the Mass. Michel Onfray, a self-described atheist, wrote last year:

The Latin mass is the patrimony of our civilization. It is the historical and spiritual heir of a long series of rituals, celebrations and prayers, all crystallized in a form that offers a total spectacle: a Gesamtkunstwerk, to use a word from German romantic aesthetics.3)

Proust too had evoked Wagner, in his view the only modern artist who in works such as Parsifal approached the beauty of the Catholic Mass! Yet, Proust affirms, a Catholic Mass celebrated in Chartres cathedral exceeds anything produced in Bayreuth.4) It is incumbent upon us to defend and preserve this heritage for the sake of the Faith and also for all mankind. And strangely enough, in so doing is not Catholic traditionalism practicing the truest kind of ecumenism?

1. Proust, M, Death Comes to the Cathedrals at 10.

2. Lewis, Michael J., “An Incendiary Plan for Notre Dame Cathedral” The Wall Street Journal 11/30/2021

3. Onfray, Michel, “Ita Missa Est” in From Benedict’s Peace to Francis’s War, (Peter A. Kwasniewski, Ed.) at 68 (Angelico Press, Brooklyn, NY 2021)

4. Bayreuth is the location of the theatre which Wagner created to present his operas.

Related Articles

No user responded in this post