Jan Bentz, Jochen Prinz (editors)

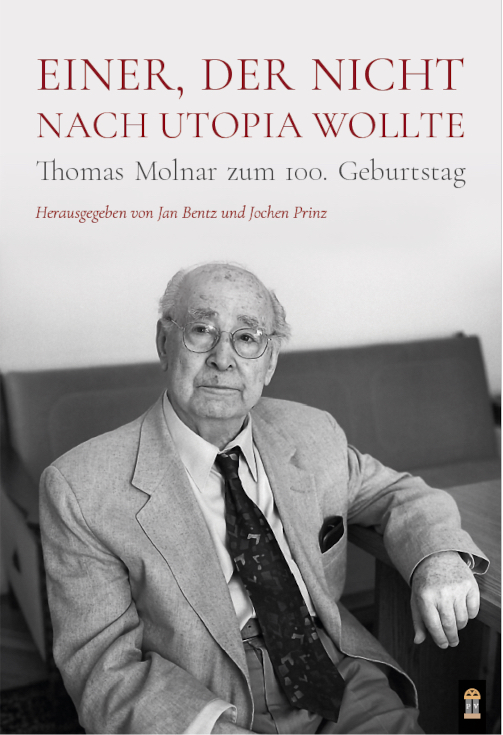

Einer, der nicht nach Utopia wollte: Thomas Molnar zum 100. Geburtstag

Patrominium -Verlag, Mainz, 2022

162 Pages

I was happy to see that last year a book was finally published dealing with Thomas Molnar. It has been a long time to wait for such recognition of a man who was once so prominent both in American conservatism and the French reactionary resistance. But finally in 2022 Molnar has received his own Festschrift – if a relatively short one. Contributors come from the United States, Switzerland, France, Hungary and Germany.

Now I certainly appreciate the efforts of all involved in putting this attractive tribute together. I cannot say, however, that A Man who didn’t want to go to Utopia is the best place to get to know Thomas Molnar. The tone of the book is too abstract. Molnar appears mainly as an academic dealer in ideas and concepts. The authors investigate the source of his ideas, try to identify influences on Molnar and discuss how Molnar fit into the conservative movement in the United States (or didn’t). Although such information has its value, it leads to a misunderstanding of the man and his work.

Of course, it is a bit unfair to expect those who are discovering Molnar primarily from his published works will form the same impression of someone with whom I conversed for many years. However, I think even a brief acquaintance with Molnar’s books and articles reveals an entirely different cast to his thought – that he was eminently practical and focused on the concrete political and spiritual problems of his time. That Molnar was, above all, a supreme analyst of culture.

His best writing usually responded to a specific contemporary development or tendency in education, politics, philosophy, ideology – or the Church. His interest was kindled by a news report, a casual remark in conversation, or something ordinary he had just seen. For Molnar such incidents of daily life could suddenly illuminate in a new way one of the “global” issues of our age. And Molnar’s perspective on these topics was not at all uninvolved but passionate and committed. Given the direction the world took over the course of his life, that passion often manifested itself in forceful criticism of the world’s dominant powers (including specific individuals and countries).

In his essay in A Man who did not want to go to Utopia, Zoltán Pető does focus on one overriding cultural concern of Molnar: the worldwide liberal hegemony of the United States that obtained its ultimate triumph in 1989/91. In a series of works from the 1970’s through the 1990’s he inveighed against the new “liberal” despotism, with its fusion of idolization of the market with the decline and disrespect of tradition, manners, and education . Molnar very clearly identifies our age with a previous era of transition and collapse: the fall of the Roman empire. And he compared himself with Symmachus, one of the “last pagans.”

Haven’t the events of the last 10 years furnished the best proof of the validity of Molnar’s arguments? The synthesis of capitalism and cultural/political totalitarianism that he denounced has become an everyday reality. But Molnar was prescient in so many other matters as well! The working out of the tendencies within the Church that he critiqued starting in the 1960’s has led to the reign of Francis. A particular target of Molnar’s almost from the beginnning of his writing career, American higher education, has culminated in the “woke” takeover and in the outright repudiation of Western civilization.

Especially in later years, Molnar turned more and more to the writing of philosophy. For he came to see as the hope for mankind not institutions but the innate, indestructible affinity and desire of man for truth and for God. It is regarding this aspect of Molnar’s oeuvre that the essays in A Man who didn’t want to go to Utopia are most helpful.

Despite the reservations I have set out, this Festschrift is a valuable contribution – especially to those intrigued by Molnar’s thought (and who can read German). I hope this book leads its readers to further investigate the works of a major figure of Catholic and counter-revolutionary thought.

In some respects, a recent (2021), much shorter, article by János Pánczél Hegedűs provides a better initial, general introduction to Molnar. ( Pánczél Hegedűs, János, “Thomas Molnar’s Lifelong Struggle against Modernism,” Hungarian Review, Vol XII, 11/24/2021). It also takes up certain issues that are still somewhat unexplored – Molnar’s biography, or his religious development (although I would not agree to some of this author’s assertions in the absence of specific authority). On a humorous note, Pánczél Hegedűs discusses rumors (which I never have heard) that Molnar had been a CIA agent!

Related Articles

No user responded in this post