We wish you and your families a blessed Easter.

Medieval stained glass windows are in the Strasbourg Cathedral in France.

11

Apr

We wish you and your families a blessed Easter.

Medieval stained glass windows are in the Strasbourg Cathedral in France.

7

Apr

(Above) The “communion package”

This time at the Catholic Chaplaincy of the University of Munich. To enable Students ( in the original German a politically correct, nongrammatical, androgynous form of the word is used) to receive communion at home. The idea is that in this time of pestilence everyone can be an “extrordinary minister” of communion – to himself. Accordingly, “divine service sets” have beeen prepared and distributed. Each contains a palm, holy water, a consecrated host and prayers. Everything is packed following the highest hygenic standards. Recipients are admonished to “treat the Host respectfully.” No need to worry – the chaplain claims he knows everyone who is receiving the set….

2

Apr

(Above) The transept of the grandiose interior.

My first encounter with this church was as a solitary visitor in the early 1980s. The interior was dark and dilapidated; like many other Victorian-era churches it had been painted in the course of time a miserable battleship gray. Only a few Vatican II-type banners, hung here and there, relieved the somber appearance.

I still have always found this church nearly empty when I have visited even on much more recent occasions – this neighborhood is no hotbed of Catholicism – but at least it is usually open. For this parish still disposes of some financial resources including rental income from real estate in the vicinity. The high school is also active.

(Above) Jesuit martyrs of Japan. A devotion to them existed at this parish as early as the 1850’s. One of the many murals in this church by William Lamprecht.

(Above and below) The two Tiffany windows of this church.

(above) A “German”style window now in the “Mary chapel.”

Now in 2000 the exterior was renovated at a cost of $2M; in 2009 it was the interior’s turn for $13M. Both now shine in relatively pristine splendor – it would be interesting to confirm whether the interior’s dominant hue of yellow is a restoration of the original color scheme. The basic decor, largely intact, consists of stucco, statues and paintings. It reminds me, with its lavishness and a certain heavy-handedness, of early baroque interiors north of the Alps, like the Theatinerkirche in Munich. Like St. Ignatius Loyola church and its mosaics, the main decorative element of the church is on the walls – paintings and sculpture-instead in stained glass windows.

But then we come to the chancel or apse which has been renovated “to embody the ideals of Vatican II.” The expanded sanctuary – now broadened into a “liturgical ministry area” – includes room for organ, choir and instrumentalists. A “Novus Ordo” altar and lecterns have been set up. The so-called “Reredos (former High Altar)”, which functions today as a large flower stand, was moved forward to create space for a new sacristy (with a skylight). Most outrageously, a large marble baptismal pool and font have been set up in before the (former) High Altar! This arrangement seems to be unique and without any historical precedent. Aesthetically, it is unsuccessful: the architectural focus of this church is occupied by a jumble of platforms, ramps, musical equipment, marble and wooden objects.

What sense then does it make for the church guide of St. Francis Xavier to boast of how ”[g]reat care has been taken to restore the rest of the interior elements (i.e.,other than the sanctuary – SC) to their most original condition?” Why talk about the fact that “one third of the hanging lamps were restored to original condition, …3 ornamental cherubs decorate each hanging lamp” while applauding the vandalization of the church’s liturgical center – the very reason for this church’s existence?1) Let us recall that a similar move by the Jesuits to renovate St. Ignatius Loyola church had been blocked by Cardinal Egan in 2002. Apparently, another Jesuit church in a more remote area of the city was not worth the same fuss – and no descendants of rich donors were on hand to intervene.

(Above and below) The former high altar with the baptismal pool before it.

(above)The altar of the three young Jesuit saints (including St. Aloysius), today an HIV/AIDS “Altar of Remembrance.”

(Above and below) St. Francis Xavier depicted in a medallion over the crossing.

David Dunlop informs us that “[f]or eight years, the church ( of Francis Xavier)offered a Mass for Members of Dignity, a group of gay and lesbian Catholics, until the archdiocese ordered an end to it in 1987.” 2) But this by no means ended the “outreach,” if anything, it was its beginning. In this respect, as in many others, St. Francis Xavier became the rightful successor of the original bastion of New York progressive Catholicism, St Joseph in Greenwich Village. This was due in part the gentrification of Chelsea, which was becoming an ever more “trendy” and tourist-filled part of town in recent decades, culminating in the High Line development.

In fact, I think it’s not unfair to say that “LGBT” ministry is today the best known aspect of this parish to outsiders. The parish’s comprehensive website reports on “Gay Catholics,” “Catholic Lesbians,” the “Transgender Day of Remembrance.” 3) An “HIV/AIDS Altar of Remembrance” stands in a transept. 4) But other issues dear to “woke” Catholics are not neglected in this “welcoming and inclusive” parish: “Zen meditation,” discussions of “white privilege,” the “migrants,” Muslims, etc.

All these concerns of course, are taken directly from the secular media and academia. Even so, following the progressive course is not without its perils. Such as when the “dancing master” pastor of St Francis Xavier parish was removed in September 2018 for “boundary violations” with a man. He had been Jesuit artist-in-residence at Boston College for 35 years and more recently ( December 2017) had staged a production at the archdiocesan Sheen center. 5)

At times the discrepancy between what is depicted and written on the walls of this building and the current attitudes and practices of this parish (and of course, those of the Catholic Church in general) shocks the conscience. Such as where St. Francis Xavier, in the great central medallion of the ceiling, is extolled as “Xavier, Virgin in Soul and Body,” and elsewhere as the “Destroyer of idols” “Helper in…pestilence.” Or where: “the crown at Aloysius Gonzaga’s feet represents giving up his noble birth to minister to those dying of plague in Rome.” 6)

I can’t deny this to the Jesuits of today: there is an undeniable audacity in daring to present in such surroundings their current theology, spirituality and way of life as a continuing “Jesuit tradition.” For their current tradition forms the greatest possible contrast to the trappings and history of this parish. A recreated Roman basilica displaying a meticulously restored nave and transept, but a gutted sanctuary and repurposed altars and confessionals; evangelizing priests, pious housemaids, military cadets and longshoremen in the past – “self-referential” liberal clergy and their lay groupies now. But isn’t the problem more fundamental – wasn’t it foreshadowed in the 1930’s when Margaret Sanger located her clinic next to St Francis Xavier church and high school? Could anything better symbolize the emerging cultural break with the West’s Christian past – a process of rupture of which the Jesuit order later became a full participant and leader ? Perhaps the parish of St Francis Xavier communicates to us this discontinuity better than any other.

(Above) A dance work by the former pastor of St Francis Xavier performed at the Sheen Center(Source: Xavier High School Site); (Below) Recent concerns of the Jesuit parish (Fall 2017)

1. For the quotes regarding the decor and renovations and for further details see generally Church of St Francis Xavier Tour Guide.

2. Dunlop, op. Cit. at 204-205.

3. https://sfxavier.org

4. Guide, supra, at 12.

5. http://www.cny.org/stories/jesuit-pastor-stages-christmas- revelations-at-sheen-center,14821?

6. Guide, supra, at 23, 12.

31

Mar

Church of St. Francis Xavier

30 West 16th Street

“Exuberantly complex, a bit offbeat and impossible to ignore” – so David Dunlap describes St. Francis Xavier Church on West 16th street.1) The complex, gray stone exterior with its jutting porch, towers over its neighbors on this quiet block, which include the buildings of St. Francis Xavier high school. Both this façade and the vast stucco-encrusted interior are indeed overelaborate, not a little heavy-handed but undeniably “monumental.”2) And across the street, not too far away, sits an old townhouse from the 1846 in which after 1930 Margaret Sanger once operated a clinic. It is indicative of our culture that this building (once again a private residence) is landmarked whereas St. Francis, the first home in the city of an order so influential in New York Catholicism and witness to so many events in New York Catholic life, enjoys no such special recognition.

(Above) The church interior; (below) The “National Historic Landmark” Margeret Sanger Clinic (now a private residence.)

Now individual Jesuits had left thir mark on the city. Most notably, the German/Alsatian Fr. Anthony Kohlmann was active in the very early days of the diocese as its vicar general and administrator until 1815. Among other things, he laid the foundation of the first St. Patrick’s cathedral. He then left and continued his career in Rome. Under Bishop Hughes in 1846 the Jesuits reentered the New York diocese and established themselves at what is now Fordham University . But their first permanent foundation in New York City itself (after a fire terminated the short-lived existence of the parish of the Holy Name of Jesus on Elizabeth Street)) was in Chelsea. Led by the indomitable Fr. John Larkin, the Jesuits laid the foundation of St. Francis Xavier parish (and college)on this site in 1850. It is recorded that assistance for the new parish and college was obtained from Mexico and elsewhere. The first church was dedicated in 1851. 3)

At that time, this part of Chelsea was a well-off district, and the Jesuits had some parishioners among the limited number of the Catholic well-to-do (although the Catholicity of some of these elite has been questioned). But the majority of the parishioners of St. Francis Xavier’s were simple workers – like the Irish housemaids who cared for the residences of the upper class. The faith of these maids “worthy models of the early Christians” was a source of inspiration:

A great number of these Irish heroines have crossed the ocean for no other reason than to gather some small income in service of American families, among Protestants, so they can send it back to their poor old parents. In a foreign land, hostile to their faith, they will suffer and do anything rather than offend in any way their faith or neglect their spiritual life. …They shine like lamps in this heretical world with the brightest piety, Christian modesty and the rest of the virtues. (Jesuit community report to Rome for Oct. 1,1857 to Oct 1, 1858.)

In 1858 the parish has more than 50,000 communions; five masses were held in the church each Sunday and one in the basement – yet many had to be turned away. A veritable myriad of parish organizations sprang up. Already by 1858 the building was completely inadequate. And in addition to all this activity at their parish and schools, the Jesuit community conducted apostolates to prisons and quarantine areas. Regardless of insinuations, then and now, one encounters in the contemporary Jesuit reports no focus on the “rich and famous.”4)

(Above) The original church of St. Francis Xavier (From A Memorial of St. Francis Xavier’s Church (1882))

On March 8th, 1877, a calamity occurred: somebody shouted fire during a crowded parish mission and touched off a stampede in which seven died. In this tragedy’s wake, the Jesuits determined to build a new church on a much grander scale. They retained for the task Patrick C. Keely, that indefatigable builder of Catholic houses of worship – by then already represented in the city by St. Brigid’s, St. Bernard’s and Holy Innocents. But in contrast to Keely’s – and New York City’s – favored neo-Gothic idiom for churches, the new St. Francis Xavier would refer to the glorious European Jesuit churches of the Counter Reformation in Rome and elsewhere. These churches were, moreover, purely Catholic, in contrast with the neo-Gothic enthusiasm shared with the Anglicans. “The Roman Basilica (compared to the Gothic cathedral) is undoubtedly better adapted to the majesty and grandeur of Catholic worship.” “The basilica (compared to the “exclusiveness ” of the Gothic cathedral), exhilirates the mind with the joyousness, the boldness and grandeur of faith, the priestly character of God’s people (1. Pet. ii,5) and the oneness of the universal church.” A similar thought process produced the London Oratory, constructed about the same time. We gather from these remarks that choice of the architecture of St. Francis Xavier was not uncontroversial at the time.5)

So Keely designed the new Jesuit church in a kind of neo-Renaissance, neo-baroque style. Regrettably, Keely built his church before the Beaux Arts movement had reached matrurity in the United States . St Francis Xavier is grand in scale and magnificent in its decoration, but not nearly as successful a work of the “Classical” architectural tradition as the London Oratory or St Ignatius Loyola, which the Jesuits built in Yorkville just 20 years later.

(Above) The old and new churches of St Francis Xavier still standing next to each other(and the college). (From: The College of St. Francis Xavier: A Memorial and A Retrospect (Meany,New York 1897))

This parish has always been known to city Catholics for its affiliated educational institutions. The high school of course is still active -for many years it functioned as a military academy. Far less well known is that in the second half of the 19th century, the College of St. Francis Xavier College was one of the largest Jesuit colleges in the United States. Graduates included the famous Fr. Francis P. Duffy, as well as the editor-in-chief and contributors to the magisterial, original Catholic Encyclopedia . But the college fell victim in 1912 to a consolidation of New York and Brooklyn Jesuit institutions of higher learning that left only Fordham University as the survivor (which did, however, retain a presence in Manhattan but in another part of town ). 6)

For by 1900 this corner of downtown, a center of society around 1865, had become a little old-fashioned and out of the way, surrounded by commercial developments. The more recent Jesuit foundation of St. Ignatius Loyola on the Upper Est Side, in contrast, was thriving in the midst of what had become the wealthiest residential neighborhood in the country. The parish of St. Francis Xavier itself seems to have remained alive and well, with some parishioners and clergy of good taste. After all, St. Francis Xavier parish acquired two (authentic) Tiffany windows – a little uncommon for Catholic churches. And in 1917 its organist, Pietro Yon, composed the “biggest hit” in the history of New York Catholic church music: Jesu Bambino.

(Above) St. Francis Xavier Cadet corps around 1912. 7)

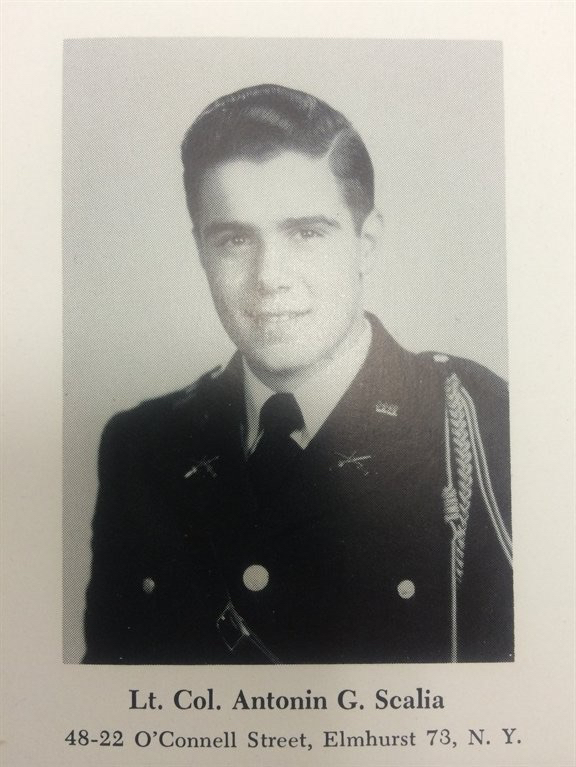

This parish’s slow drift into obscurity continued as the twentieth century advanced. Chelsea was now, as a whole, predominantly commercial and industrial. It is characteristic of the changed status of this once grand neighborhood that Margaret Sanger in 1930 would choose to set up shop here – across from a Catholic high school no less. Also revealing of those times was the apostolate of Fr. John M. Corridan, of the Xavier Institute of Industrial Relations, whose exploits on the gritty Chelsea docks inspired On the Waterfront – and also resulted in clashes with Archdiocesan mission to the Port of New York at nearby Guardian Angel parish. By the 1950’s Catholic New Yorkers outside of this area knew St Francis Xavier’s, if at all, only for its high school. A 1953 graduate was one Antonin Scalia. 8)

30

Mar

Freiburg Cathedral: The great past of Germany. Ida Görres lived in Freiburg and her funeral service was held at the cathedral.

Görres continues as our witness for the immediate post-Conciliar period. But we now encounter her in letters exchanged with a priest friend, Paulus Gordan OSB, a monk of the Abbey of Beuron, between 1962 and 1971. This correspondence was only published in 2015 – decades after the author’s death. The style of these private letters differs radically from the soporific, lecturing prose of Broken Lights. Görres’s language here is colorful, making much use of colloquialisms, slang and dialect. Capitalization of entire words, liberal use of the exclamation point and frequent underlining further emphasize the author’s often excited discourse. Of course, these letters are in Görres’s own language, while I had to make do with a translation for Broken Lights. ( The translations are my own; I have given the date of the letter from which a quote was taken ).

The letters Paulus Gordan sent to Görres have not been found. From the evidence of Görres’s reactions to them, however, he seems to have been your average complacent member of the clerical establishment. His main message is that there are no problems or emergencies, everything is under control, don’t get alarmed, “keep calm and carry on.” His personal theological opinions, as reported by Görres, were progressive – he seems to have thought that his own order’s founder was “mythical”; entertained the idea of each order replacing devotion to its founder with exclusive devotion to Christ; and raged against those ignorant obscurantists opposing the Council. Is it any wonder that in 1968 he received a high Roman post in the Benedictine Order working directly under none other than Rembert Weakland OSB?

The image of this collection’s title derives from the hopes of those who, like Ida Görres and Paulus Gordan, initially celebrated the “creative destruction” of the Council, the breaking down of walls, regardless of the consequences. In her early letters, Görres and Gordan applauded (with some trepidation)the destructive forces loosed by the Council, for, so Görres hoped, the Church would rise again like the mythical Phoenix from the ashes of the consuming fire, as it had done so often in the past! (I am not certain of the soundness of our letter writer’s grasp of ecclesiastical history.)

By 1966, however, she was not at all so sure:

No man can even guess what will be swept away and buried by the avalanche that has been set in motion. Nor, whether what will spring up as new life out of the ruins – we will not experience it – will be really a new form of phoenix or simply something other, totally foreign, not-identical, that doesn’t involve us at all. (January 21 ,1966)

For from the beginning of this correspondence she was traumatized by the new phenomena of the 1960’s, great and small. Some examples:

An article appeared in a Catholic publication, supporting womens’ ordination and finding that the legend of “Pope Joan” reflects an “age-old” wish of Christendom. Görres calls it ”a brazen Goebbels-like distortion of history!” (February 10, 1966). The editor’s open support of these views stood in stark contrast to the treatment of an article of her own on the same subject in another publication, where letters to the editor supporting Görres’s position – which we gather was different from the first-mentioned article – were suppressed.

I have nevertheless the deepest skepticism when monks’ vows can be so easily annulled. …The pendulum has swung immoderately to the consideration only of the purely subjective instead of, as the case earlier even to the point of cruelty, the objective. (February 15, 1968)

Now everything at once has to be cut down to the late 20th century. Why really?… Just as in ten years one will probably have a fit of cramps over the greater number of churches built today – but by then they will stand, cast in concrete and having cost millions, as a permanent horror of the incarnated soul of 1960-70 – and will remain. (November 4, 1968)

One of the strangest and most questionable traits of the present age is just this rage against the “sacred” in all areas. No abuses can really explain this rage – I sense behind it so much the diabolical offensive.”(March 7, 1968) Later in the same letter, however, she astutely ties it to “democracy.”

(Görres received a letter from an acquaintance visiting India who reported) that on the ship were ten Catholic priests who mostly concelebrated “in an incredible competitive tempo to see who could talk the fastest” – so much so that friend travelling with her, who wanted to turn to Christianity, was so disgusted that she decided not to concern herself any more with Catholic Church but rather to approach Protestantism. (April 7, 1968)

Görres was disgusted with the invitation of her “Pan-European” brother Richard to take part in some kind of St. Benedict ceremony in Subiaco. Her brother told her of the event over the phone, laughing loudly. “The old mocker and cynic, who believes in nothing but himself and his “Pan-Europe”(whatever that is). … He visited the pope a few years ago and the picture is hilarious. He made a face like that of a patronal lord of olden times who has just condescended most graciously to visit his village priest.” (June 19, 1970)

A special cross for Ida Görres was the departure from the priesthood or religious life of acquaintance after acquaintance who had, she thought, in their lives harmonized Catholicism and ecumenism, modernity, etc. One American Jesuit, well-known to her, who left that order to marry, actually used the later Bergoglian term “Lord of Surprises” in justifying his actions! (April 21, 1969)

Yet, we must remember that Görres largely confined these thoughts to private correspondence. Outwardly, Ida Görres, a classic “professional Catholic,” continued to fulfill the role assigned to her by the Church establishment; that of the mildly progressive but obedient daughter. In these very years, for example, she published books and articles about “Saint” Teilhard de Chardin as she once did about St. Theresa of Lisieux – it was almost self-parody. She wrote a review attacking Dietrich von Hildebrand’s Trojan House in the City of God – although privately she agreed with much of what he wrote. It seemed that after the Council criticism of the existing Church – as in Broken Lights – was no longer desired. Unless, that is, it emanated from the progressive wing.

Finding herself to be more and more some kind of “conservative,” Görres looked about for like-minded religious and intellectuals. She quoted a message to her from Mother Theresa: “Write for the very simple people, tell them what the Council really wanted….The Council must have been really a great thing since the devil makes much effort to confuse and erase its sense” ( July 27, 1968.) Neither Görres nor Mother Theresa adduces any evidence for this statement which later became an article of faith among conservative Catholics.

But Görres’s new hero was one Joseph Ratzinger. “By the way I have found my prophet in Israel!” She praised him effusively: “he can become the theological conscience of the German Church” – and contrasted him favorably with the “compromised” von Hildebrand. (November 28, 1968) At least initially, Fr. Ratzinger does not seem to have reciprocated the interest of his garrulous admirer. An initial communication from Görres received a cold, formal reply. And Fr Ratzinger was not at all amused when Mr. and Mrs. Görres “dropped in” at his dwelling to visit him. A second meeting in the town of Regensburg apparently went much better but no details are provided. (July 15, 1970)

Things came to a head in 1970 with the start of preparations for the Würzburg Synod (1971-75) which would set the course of the “German Catholic Church” for decades. Invited to participate, Ida Görres now would have to assume a public role instead of remaining an observer and commentator. She had the misfortune to experience firsthand how far affairs had progressed in Germany since the Council. Görres was by now completely out of step with the times, a “dinosaur” ( she compared herself to Rip van Winkle). We can sympathize with our author’s hurt vanity when someone, meaning to be kind, told her she had read in the 1930’s a few things by Görres and how much it had influenced her….

Again and again Görres lamented the lack of character and strength exhibited throughout this synodal process by the clergy religious and especially the hierarchy. In a kind of “listening session” early on, she and a few other members of the synod had to sit “in the dock” before a crowd of 100 students “not paper tigers, but paper sheep, without initiative, fire or insight and only spouting clichés.” The attending student chaplain declared “they would not let anyone ‘take intercommunion away from us‘ – which they were already practicing.” (December 4, 1970)

“The bishop is a poor silly goose, really pathetic. He sat fearful, defensive, intimidated and only gasped when something displeased him.” ( December 20, 1970). There was much talk but no real conversations or exchange of ideas. She was shocked that an assembly of this kind was supposed to make decisions. Görres objected to the practice of selecting synod participants by their membership in this or that group or class: women, students , workers, youth etc. ( a practice that has become normative everywhere today). “The bishops are ‘as silent as eggs’ as the Japanese proverb has it“– one of them indeed was “soft as wax.” (February 15, 1971). On the other side of the fence were “choleric personalities, dynamic, impatient, terribles simplificateurs, demanding immediate action and lacking the patience to think things thorough in a multifaceted analysis. Goethe: “nothing is more dangerous than active ignorance.’ ” Under the circumstances, Görres had to play too often the role of the enfant terrible – “but the reaction was not hostile, mocking or even lenient-tolerant – just totally non-comprehending.” (May 11, 1971)

In the second official session of the synod Görres collapsed and died. She fell, as her fellow hagiographer Walther Nigg put it,

“on the field of honor” (in other words, on the battlefield). Her funeral took place in Freiburg cathedral – she and her husband had been living in that town for many years. Fr. Joseph Ratzinger gave the homily.

As we have seen, the status of the Church in Germany in the 1950’s – a nation so influential at Vatican II, was a most unlikely foundation for spiritual renewal. On the contrary, the climate prevailing among the elite was not of emerging sanctity and sacrifice but of intellectual conceit, carping criticism, deference to modern society and dissatisfaction with the entire remaining body of “Catholic culture” ( the “Catholic milieu” or the “ghetto”). It made inevitable the crisis that exploded as soon as the Council gave these tendencies official approval. Almost immediately symptoms of disintegration manifested themselves in almost every aspect of Catholic life.

In this maelstrom, a minority of Catholics like Ida Görres very much wanted to retain their progressive credentials and remain a part of the establishment yet nevertheless couldn’t close their eyes to events and facts. Görres could no longer engage in wishful thinking and fables about the advantages of destruction and rebirth or conceal from the general public – and herself – the facts of the scale of the “avalanche” overwhelming the Church. She and like-minded people rejected Traditionalism and the strict defense of the Latin Mass which were just then in their infancy. Some of the positions and alliances which Görres did privately endorse later became part of the repertoire of “Conservative Catholicism.” But for Ida Görres none of this support had yet materialized. She succumbed, abandoned by the hierarchy at their own synod. We have seen in our own time how her fearful vision of the Catholic Church being transformed into something utterly alien has become so terribly true, at least for Germany.

Within a few years she was completely forgotten. But she has left us a precious record of those days – a record not just of facts but also of surprisingly prophetic insights. A legacy doubly important as these same issues and the same leadership continue to haunt us today – and not just in Germany.

28

Mar

(Above) Ida Görres

Broken Lights: Diaries and Letters 1951-1959

by Ida Friederike Görres

Translated by Barbara Waldstein-Wartenberg (The Newman Press, Westminster 1964) (German edition: 1960)

“Wirklich die neue Phönixgestalt?” Über Kirche und Konzil: Unbekannte Briefe 1962-1971 an Paulus Gordan

by Ida Friederike Görres

Hanna-Barbara Gerl-Falkovitz (Editor) (Be & Be Verlag, Heiligenkreuz, 2015)

You may wonder why I speak of the “collapse” of the German Church. Hasn’t the German Catholic Church – their theologians, their charitable organizations and above all their government money – acquired unprecedented influence over the entire Catholic Church under Pope Bergoglio? I am referring, however, to a transformation that took place between 1945 and 1971, in which the Church in Germany acquired an entirely different substance while retaining the hallmarks of the past: institutions, folklore, pretty churches and orchestral masses. A “sea-change” which would – except for certain pockets of resistance – eventually almost extinguish the practice of Catholicism in that country.

Ida Görres is an important witness to this transformation – initially, as a committed supporter of change, then, as an aghast observer of calamity. Her background may be surprising: born in 1901 into Austrian nobility (her brother was the one-Europe, one-world agitator Richard van Condenhove-Kalergi; her mother was Japanese). She had married Carl-Josef Görres; I have found no reference indicating he is a relation of the great 19th century Catholic journalist and thinker Joseph von Görres. A committed Catholic writer, Ida Görres was best known for her hagiographical works of the 1930’s and 40’s – for example, on Mary Ward and Theresa of Lisieux.

From 1950, she was compelled to live as an invalid – so most of the first book we are considering, Broken Lights, takes the form of reflections on her reading. In her diary and letters Görres rambles over all kinds of topics, but returns again and again to her own vocation of hagiography. She discusses many saints and holy people, major and minor. And even the living: for example, there is a reference to Mother Theresa some 15 years or more before she became generally known in the English-speaking world (p. 196). I certainly would like to know more about some of these figures!

The general tenor of Ida Görres’s remarks is one of unease and dissatisfaction with the Church. She seems on the quest of a new “core” underneath the inadequate exterior of contemporary Catholicism, a pearl under the ugly shell of the oyster:

Nothing saddens me more at the moment than the pitiable mediocrity and flatness of Catholic Christendom – I can hardly find one redeeming feature anymore. (p. 51)

And, of course, there are references to the Catholic “ghetto.”

Perhaps as a result, Ida Görres ranged widely afield in her reading: Jewish texts, gnostic writings, mystical and spiritual literature of all kinds, novels – but also Newman and C.S. Lewis. I cannot say that everything she says on this mass of reading is insightful – she excoriates Simone Weil but has some semi-positive words for The Power of Positive Thinking by Norman Vincent Peale!

Even in her chosen field of hagiography, the strongly Catholic figures that that once fascinated her are now found to be inadequate or at least in need a radical reinterpretation:

In one way Mary Ward has grown rather strange to me, remote. For her external story represents a model belonging to the very earliest phases of my spiritual life, a model now outdated; the typical zealous figure – almost zealot – of the Counter Reformation.

I have been ruminating on Mother Francis Xavier Cabrini, surely a classical example of that special, perfectly genuine and lawful brand of Christian piety which can be completely unintelligent… In 67 years of holiness truly lived… there is no record of a single “unforgettable sentence”… Completely devoid of self-reflection. One feels almost inclined to say: if animals could be holy, they would be holy this way. (p. 364)

For me, the attitudes, as revealed in his book, of our author and, even more so, of some of her dialogue partners reflect negative characteristics of German Catholicism that have remained until the present day: the striving to appear smarter, not to be holier, than others; the constant assertion of an allegedly enlightened present over previous years of ignorance and conformity; the resulting compulsion to jump on the band wagon of current secular trends; and, finally, resentments against the concrete manifestations and heritage of a (at that time, still extant) Catholic culture.

Now it would be unfair to regard Ida Görres as a mere scribe for the platitudes prevailing in 1950’s Catholic intellectual circles. Here and there she exhibits flashes of brilliance, makes pointed observations, dissents from the intellectual mainstream. Such as in her extensive reflections on marriage – both mystical and concrete, e.g.: If marriages are going to remain deliberately sterile, then there is no longer any logical, conclusive argument against homosexuality (p.112). Or her decidedly un-Maritainian view of the United States: For me America is a symbol: symbol of the sort of ”modernism” I cannot endorse or acknowledge and can only accept with inner protest…. (p. 321). Or her repeated expressions of her joy in the (old) liturgy: I just revelled in that High Mass at Beuron Abbey on All Saints’ day. Once again “the liturgy as drama”, nothing purposeful about it, praise and thanks giving to God as art pour l’art, as natural as the liturgy of the angels before the heavenly throne, devoid of all pastoral instructional “consideration” for the congregation which, for that very reason, was carried away by it all, borne on its wings. (p. 329) This, in the face of one of her acquaintances denouncing this very celebration as mere “spectacle,” “play acting with the congregation just spectators.”

And, finally, what of this weirdly prophetic passage, resonating so clearly at this very moment:

(Referring to actions supported by the Rockefeller Institute in the Philippines) Most extraordinary how nowadays the craze for health can authorize super democratic – professionally democratic – people to resort to the kind of cold-blooded sanitary terror enforced in… areas stricken by epidemics and pestilence. These shock-troops coolly did things which, done in a political cause, would be branded as the most flagrant infringement of human rights of every kind. Here they are apparently taken for granted, indeed even regarded as humane and commendable: houses broken into by force, families torn apart, removal of the sick, destruction of property, houses and furniture etc. … the author’s casual comment: “our educational campaign against these deep-seated prejudices was like a conversion to a new religion” is much more telling than he knew: a new cult and a new scale of values was indeed introduced here. (pp. 259-260 )

Towards the end of the book Ida Görres does sense that she had fallen behind the current tide:

I know you (and lots of other people) think I’m too “Right-wing”, “Papist” , conformist, old-fashioned, too submissive to the clergy. (p. 313)

Yet she nevertheless reaffirms her faith in the “Church to come” and views herself as a transitional figure:

The Church of Today, which is as much my concern as the Church of Tomorrow is that of the reformers. In me the present Church in changing if only in one tiny fragment, into the Church to come – that is the nucleus and meaning of my destiny (p. 315).

This book witnesses that the German Catholic Church of 1959 was in a “pre-revolutionary” situation (much like that of France in 1789). And just as in 1789, the Vatican and the bishops didn’t seem to comprehend what was going on. The “good old days” of Pius XII really didn’t exist. The old landmarks had become obscured – the new had not yet come into view. Therefore, the title of Görres’s book in the original German is well chosen: Between the Ages (or Times).

A word needs to be said about the 1964 English-language edition. By that year, the Catholic Church in England was itself being rocked by first wave of the Vatican II changes. Four years after its initial publication, Ida Görres‘s book was furnished with a new title emphasizing not just transition, but the collapse of the old order: Broken Lights. And some not very accurate comments provided on the dust jacket simplified and radicalized the message of the book:

Her particular interests center on the discrepancies between the beliefs and practices of Catholics, between the conventional, false images of God and His true Revelation and upon the many manifestations of the ultra, ultra Catholic conservatives with tight, closed, prim, authoritarian and infallible views.

.

28

Mar

In time for Passion Week:

St. Mary Church, Norwalk will begin live streaming Masses tomorrow from the parish website: http://www.stmarynorwalk.net/main/

Traditional Low Mass tomorrow at 9:30 am

27

Mar

Una Voce: The History of the Foederatio Internationalis Una Voce

Leo Darroch

(Gracewing, Leominster 2017)

I have long been interested in the story of American Catholic Traditionalism. Una Voce: the History of the Foederatio Internationalis Una Voce is an account of Una Voce, one of the main protagonists in Europe, written by a former president of that organization. I find it an invaluable contribution to our knowledge of the survival of Traditionalism – yet some major reservations and qualifications are necessary.

To start, this book might be more accurately titled “Materials for the History of the Foederatio Internationalis Una Voce.” For Darroch’s book is in no way a complete history of the Una Voce federation, let alone that of post-Vatican II Traditionalism. Rather, it is the story of the center or headquarters of the Una Voce organization, its status reports and above all its discussions over the years with Vatican representatives. The president of Una Voce (international) freely admits that at times he has very little idea of what is happening in the local chapters, where much of the actual work of the federation in education and publication was being done. Some of these, such as the UK and German chapters, were established early and continued to play a major role throughout the period covered by this book. Others, like the United States organization, flowered early, vanished and reappeared in different reincarnations.

One would very much like to hear more of the experiences of the main national chapters. The Latin Mass Society of the UK, for example, was involved in the granting in 1971 of the only real concession to the Traditional Mass made by Rome prior to 1984/88: the “English” indult. (This book, however, makes clear how extremely limited this concession was.) There is also mention that in some chapters a more defiant attitude regarding celebrating the Old Mass continued to exist “under the radar screen” of the international headquarters.

The format of this book may also be challenging for readers other than dedicated historians. For the text consists largely of verbatim reports, interviews, minutes of meetings and letters, at the expense of a coherent narrative. Questions of substance and procedural intricacies, fundamental discussions of principle and bureaucratic trivia are freely mingled here; critical issues arise and are then suddenly dropped in mid-stream. On the other hand, a chief contribution of Darroch’s book is indeed the generous selection of excerpts from the original documents!

We have spoken of the president of Una Voce. This book is indeed largely the history of one man, Eric de Saventhem, the founding president of the International Federation, who sustained the efforts of the federation’s center with his energy, persistence – and, probably, financial resources. It is to his credit, first, that at least some central point of contact was retained for the “Uniate” ( basically, “non-Lefebvrian”) Traditionalists. Second, Una Voce preserved throughout the decades its advocacy of the pre-Conciliar Mass and never deviated into the so-called Latin (Novus Ordo)Mass that gained such a hold on “Conservative Catholics” in the US. Third, de Saventhem left us such memorable and visionary statements of principle as:

A renaissance will come: asceticism and adoration as the mainspring of direct total dedication to Christ will return. Confraternities of priests, vowed to celibacy and to an intense life of prayer and meditation will be formed. Religious will regroup themselves into houses of ‘strict observance.” A new form of ‘Liturgical Movement” will come into being, led by young priests and attracting young people, in protest against the flat, prosaic, philistine or delirious liturgies which will soon overgrow and finally smother even the recently revised rites…

It is important that these new priests and religious, these new young people with ardent hearts, should find—if only in corner of the rambling mansion of the Church—the treasure of a true sacred liturgy… (Address to the Una Voce United States chapter in June 1970)

How could the aspirations be better articulated – and so early on! – for a movement that would demand so much personal sacrifice with so little hope of success over so many decades?

De Saventhem had, however, far less success as a would-be ecclesiastical politician. His attempts over the decades to obtain some kind of concession or deal from the Roman authorities

with whom he was in fairly regular contact had, by his own admission, absolutely no success prior to the indults of the 1980’s. And, as we can infer from this book, the concessions of the Indults were entirely due to the efforts of Archbishop Lefebvre, not those of Una Voce. Indeed, de Saventhem’s bureaucratic maneuvers and proposed compromises served only to undermine the credibility of a movement allegedly based on the highest principles. Inevitably, wishful thinking seems to color de Saventhem’s reports. At times, he grasped for signs of papal favor (under Paul VI!); on other occasions he talks of parties in the Vatican more or less sympathetic with the Tradionalist cause. One feels thrust back into the era of the Cold War Kremlinologists, who in search of the will-o’-the -wisp of détente, constantly sought to identify alleged “moderate” and “hardline” factions in the Soviet leadership. It was a futile endeavor for Una Voce as well: the rudeness, arrogance and duplicity of the Vatican and the hierarchy in general is laid out here in great detail. One should read this book to understand the FSSPX’s well-founded distrust of the Vatican. There is also abundant evidence of the vacillations of Pope John Paul II.

Archbishop Lefebvre, on the other hand, after a late start even subsequent to the foundation of Una Voce, focused on preserving the celebration of the Traditional mass at all costs and, increasingly, regardless of ecclesiastical permissions. To do that he began by training missionary priests in his own seminary adding schools, communities of sisters and affiliates such as Traditional Benedictines, Dominicans and Redemptorists – and, finally, in his most dramatic step, bishops. It was a course of action that had been put on the table in the early days of the formation of Una Voce but not adopted (at least not by the federation’s headquarters). De Saventhem seems to have been in communication now and then with the Archbishop whose movement, in contrast to the static situation of Una Voce, continued its steady and relentless growth.

Of course, this was not just a case of mistaken tactics on the part of de Saventhem. More fundamental factors were in play, whether or not the main players of that era could or would have been willing to articulate them. De Saventhem remained in practice wedded to an “ultramontane” ecclesiology wherein the liturgy was the creation and property of the papacy. Therefore, the principal focus of Una Voce’s center was “negotiations with” ( for most of this period, more accurately: “supplication of”) the relevant Roman authorities. Archbishop Lefebvre, however, given his background as a missionary, must have sensed the radical loss of faith underlying the developments of the 1960’s. While Una Voce – or at least its central leadership – saw saving the Mass as a bureaucratic exercise, Lefebvre understood it as a spiritual problem, a challenge of evangelization requiring the radical refounding and reconstitution of Church institutions. Of course, Archbishop Lefebvre’s policy was also superior from the purely secular perspective of negotiation tactics (he was, after all, conducting his own discussions with the Holy See). For while de Saventhem could only talk to the Roman prelates of the personal attachment of some of the faithful to the Old Rite, citing petitions and surveys, Lefebvre commanded a growing institutional following that was causing acute embarrassment to Rome. Something had to be done!

The indult of 1984 and even more so the motu proprio Ecclesia Dei of 1988 combined with Archbishop Lefebvre’s ordination of bishops in that year changed all this. A large number of Lefebvre’s priests and affiliates could not follow him in the latter action. Suddenly, Una Voce acquired substantial institutional and clerical allies. Now there was indeed more to talk about at the Vatican as Ecclesia Dei was rolled out! Furthermore, the hostility of the Roman authorities softened somewhat and there was a new dialogue partner – the Ecclesia Dei commission. Nevertheless, Una Voce had to contend with the unabated hostility to Traditionalism of other ecclesiastics in and outside of the Vatican who would continue to defy implementation of the 1988 Indult.

The most dramatic incident of the post-Indult years occurred, however, under the presidency of Michael Davies, who succeeded de Saventhem in 1995. For it was under his watch in 2000 that the future conservative hero, Cardinal Castrillon Hoyos, launched out of a clear blue sky an underhanded attempt to impose “adaptations” derived from the Novus Ordo on the Traditional liturgy. Davies and Una Voce, exhibiting greater firmness than the preceding Una Voce administration had shown, resolutely opposed this move. The initiative, which would have destroyed non – FSSPX Traditionalism, was quietly allowed to die. Here Una Voce did indeed show its worth.

There are many other gems and curious facts scattered about the pages of this book. It is admittedly incomplete. Yet, if you want to get a sense of what in particular early Catholic Traditionalism was like – and the forces it had to contend with – it’s a great place to start

24

Mar

There are a few priests who have risen to the occasion. One of them is Father Joseph Scolaro, who has planned an extensive Eucharistic procession tomorrow covering a big expanse of his neighborhood.

Here’s what his notice says:

“You may not be able to come to the church to see the Blessed Sacrament… but he can come to you!

“Father Scolaro will be going around town with the Blessed Sacrament this Thursday beginning at 4 pm. Visit https://tinyurl.com/sbvlqkl to see a detailed route.

Please meet us anywhere along the route. We will be posting updates as we hit every mile marker on the map. Out of reverence for the Blessed Sacrament we’re invited to genuflect as Our Lord passes and we receive His blessing

“We ask that you do not follow us in procession, but rather greet the Blessed Sacrament from a distance outside your home.”

24

Mar

A screen shot of this morning’s 7 am Low Mass at St. Patrick’s Church, live-streamed.

Father Michael Novajosky will celebrate a Missa Cantata at 6 pm this evening at St. Patrick’s Church in Bridgeport, CT. It will be a Votive Mass in Time of Pestilence. The Mass will be live-streamed from the Cathedral Parish website.

Father Novajosky has been posting a daily schedule of live-streamed Masses on this website, including a daily Low Mass at 7 am. He is planning add more to the schedule.