(Above) The cathedral (being renovated) against the background of one of the neighboring skyscrapers.

(Continued from part one)

If, prior to 1950, the never-ending process of embellishment and restoration had been a story of steady improvement, the post-Conciliar experience was anything but. Cardinal Cooke, for example, substituted statues of Mother Seton and Bishop John Neumann, in a grotesquely clashing style, for two of the Victorian-era side altars. Cardinal O’Connor went much further. He made significant changes, all under the rubric of “bringing the liturgy closer to the people” and making it “more visible.” A totally unnecessary “people’s altar” was inserted before the high altar, throwing the entire focus of the cathedral out of kilter. Bright lighting was installed, only demonstrating how little the Cardinal and his clergy knew about Gothic architecture. Finally, television screens were deployed around the nave. At some point in these years the two large altars in the transept were “repurposed” as a baptistery and shrine to Our Lady of Guadalupe. But despite all these painful mistakes, we can be grateful that, as a whole, St. Patrick’s was spared the post–Conciliar gutting inflicted on so many of its sister churches.

Cardinal O’Connor’s two successors retreated from some but not all of these mistakes. Among other repairs, Cardinal Egan substituted for the short-lived statue of John Neumann a new, more stylistically appropriate altar of Our Lady of Czestochowa. But the elements of this new altar had been seized from the magnificent church of St Thomas in Harlem, which the Cardinal had destroyed. We see here an unfortunate precedent: improvements to the cathedral begin to rely on the destruction of other Catholic churches.

We now come to the current restoration effort. Although the Cathedral has benefitted from more ongoing work than any other Catholic church in New York, Cardinal Dolan nevertheless felt inspired to commission a $171 million restoration. We have heard that the effort has left the Archdiocese very indebted indeed; we fear that the indebtedness will be financed out of the sale of other New York churches and their real estate.

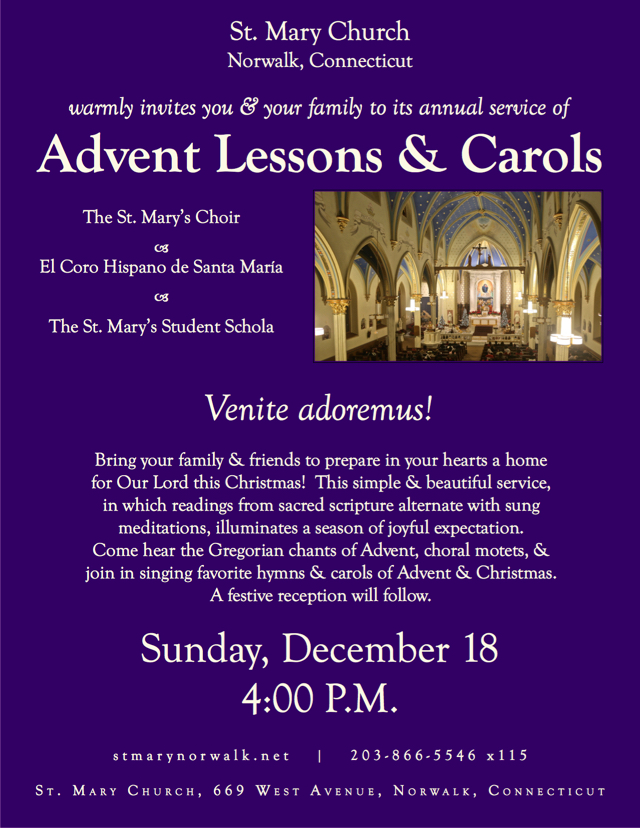

What of the new restoration, now completed? Let me comment on the aesthetic impression, as opposed to the structural benefits. On the outside, the shining white church looks fine; one can now distinguish the different courses of stone. The results in the interior are more debatable. The bright, cleaned surfaces of the walls and ceiling, combined with the continued use of dazzling lighting, create a non-Gothic environment in which the stained glass, instead of illuminating the interior, recedes into the background.

And what of the life of the cathedral today? My knowledge of St. Patrick’s liturgical life in recent years admittedly has been restricted to the weekday afternoon services. The music, the preaching, the vestments and the ceremonial are dreadful; what kind of impression does this give to outsiders of the Catholic Church? For at all times a vast crowd of tourists circulates, vastly outnumbering the worshippers. A shop has been set up near the entrance for the convenience of all these guests. Innumerable stands for votive candles are placed around the church; they do remain popular. The candles thankfully are real, but for a number of years now their price has been doubled and their size cut in half. One thinks of J.K. Huysmans’s remarks about certain faithful “cheating God” with their (artificial) candles at Lourdes. What about the half-size ones here?

Fortunately the Eucharist is not the only sacrament celebrated at St Patrick’s; the sacrament of penance is one of the best options in town. But just be sure you arrive at the start of confession time – you will likely face a wait of a half hour or more!

So St. Patrick’s remains today more or less intact as a work of architecture. In contrast to almost every other Catholic church in Manhattan – except, perhaps, one or two commuter churches – it maintains a strong presence in the popular mind. In this age, these are real accomplishments. And in November 2016 even the Latin Mass returned to St Patrick’s for the first time since 1997. Does that herald a rebirth of liturgical and musical excellence? Will St. Patrick’s Cathedral no longer just seek out celebrity but aspire to the exercise of real spiritual leadership?

The side altars of the cathedral, (Above) The altar of the Holy Face (1891) which so impressed me as a child; (Below) An example of the famous “white marble” statuary beloved by the New York Irish.

(Above) This altar (erected after 1908) is a creation of Tiffany studios; (below) it was donated by the Bouvier family. Their descendant: Jackie O!

The stained glass of St Patrick’s has been created by artists not usually represented in New York Catholic churches and often depicts images that are unusual – even startling. The earliest (1879) glass came mainly from the Lorin studio in Chartres; of New York Catholic churches only St Jean Baptiste has a large set from this source. (Above) St. Henry Emperor of Germany warring against the “Slavonians” with saintly assistance. Cardinal Farley’s opinion in 1908: “It would do honor to the Louvre!”

(Above) The approval in 1725 of the constitution of the Christian Brothers (whose founder also has an altar in the cathedral).

(Above) A “dissolute monk” takes a shot at St Charles Borromeo, who is miraculously saved. (Below) St Charles Borromeo leads a procession among the plague victims of Milan – another favorite of Cardinal Farley. Windows donated by Lorenzo Delmonico – at that time the proprietor of the most famous restaurant in New York.

(Above) St Lawrence. (Below) Part of a window donated by James Renwick (who was not Catholic). The architect presents the plans of the cathedral to Archbishop Hughes. Disregarding normal notions of time, Cardinal McCloskey ( who built most of the cathedral) stands at his side, his hand on a diagram of that part of the cathedral’s plan which he altered . “James Renwick, Esq, New York” can be read on the portfolio propped against the desk. Lorin, the artist who created most of the original stained glass, can also be seen.

(Above and below) St Patrick’s features not one but two maiden saints being menaced – and then saved by divine intervention:(Above) St Susanna: (Below) St Agnes.

(Above) St Alphonsus Ligouri gives speech to a dumb man with a statue of the Madonna.

The installation of the much more sophisticated windows in the Lady Chapel by the noted English artist Paul Vincent Woodroffe lasted until 1932. (Above) A Bolshevik topples a cross.

Above him, the “goddess of liberty” of the French revolution sitting on the altar of Notre Dame cathedral

Sources:

(Anonymous) St. Patrick’s Cathedral, New York (West Chester, The New York Catholic Protectory Print (sic) 1879)

Farley, (Archbishop)John M., History of St. Patrick’s Cathedral (Society for the Propagation of the Faith, New York, 1908)

Carthy, Margaret, A Cathedral of Suitable Magnificence:St Patrick’s Cathedral New York (Michael Glazier Inc., Wilmington, 1984)(good on many of the parish activities of the Cathedral)

Basile, Salvatore, Fifth Avenue Famous: the Extraordinary Story of Music at St . Patrick’s Cathedral (Fordham University Press, New York 2010)