At St. Mary Church, Greenwich, CT, on Monday May 18 at 7:30 pm, there will be exposition of the Blessed Sacrament with Rosary, Litany of Our Lady and special music in honor of Blessed Virgin for the Month of May. We will conclude with Solemn Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament.

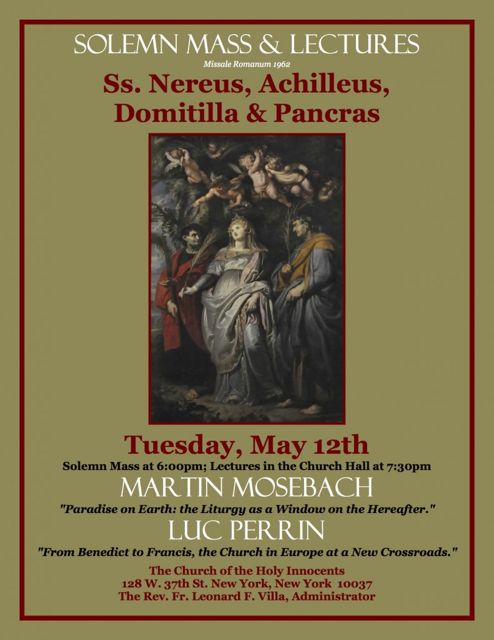

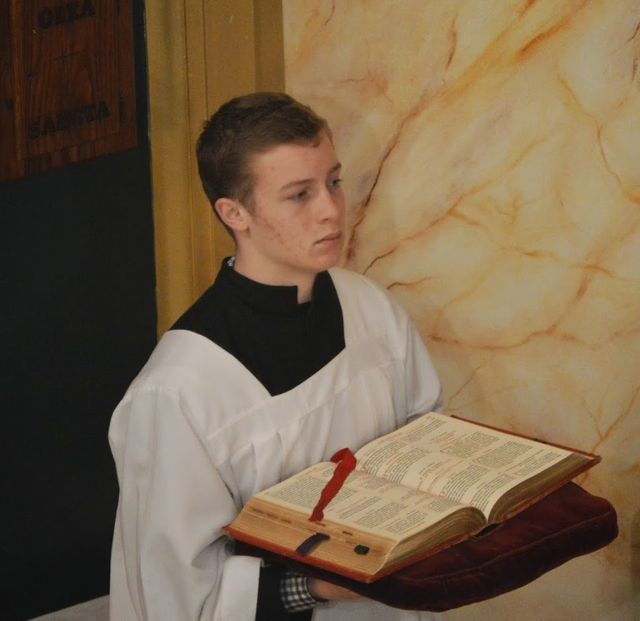

On Tuesday, May 26th at 7:30 pm we will celebrate the Feast of Saint Philip Neri with a Solemn High Mass in the Extraordinary Form of the Roman Rite

![Mass for St. Mark - Our Lady of Esperanza - 25 April 2015[4] - Version 2](https://sthughofcluny.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/144.jpg)

![IMG_0434[1]](https://sthughofcluny.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/140.jpg)