Beginning this Friday, August 5, the First Friday of the month, a group will be meeting at St. Mary’s Church, Norwalk, CT, to attend the 8 am Traditional Mass and pray the Rosary for the continuation of the Traditional Mass in the Diocese of Bridgeport, in our nation, and in the Church worldwide.

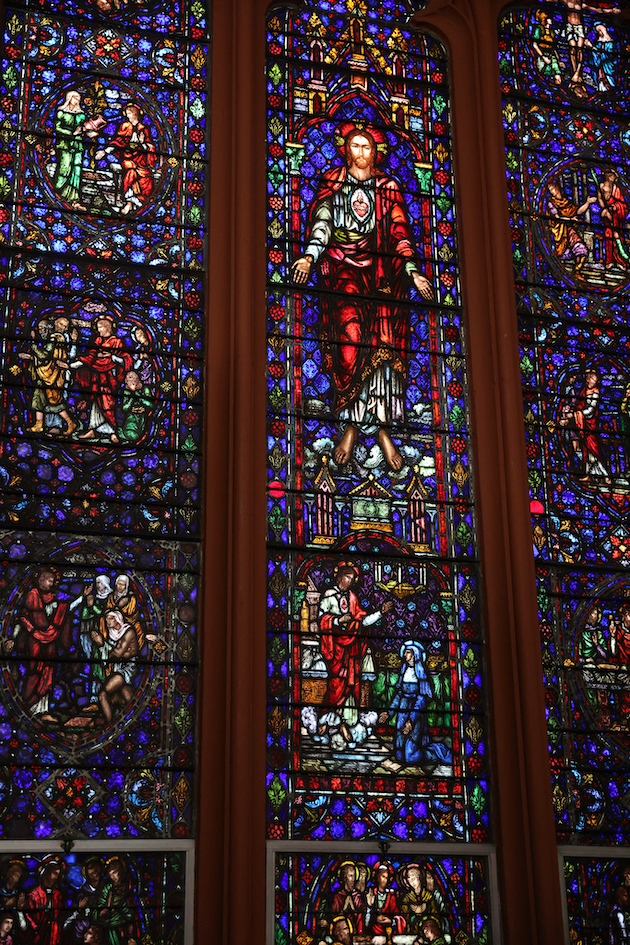

We will be praying in particular for Bishop Caggiano, who has so far recognized and appreciated the vitality of Latin Mass communities in the Diocese. But many bishops are now prohibiting Traditional Masses, either drastically cutting down or eliminating them completely.

It is urgent right now to pray that God will protect our access to the Traditional Mass and bless our priests who celebrate the Traditional Mass.

Please join us by attending the 8 am Traditional Mass at St. Mary’s Norwalk every Friday in August, starting this Friday, and stay for recitation of the Holy Rosary. If you cannot be there, consider uniting yourself in prayer.

Please invite your friends and family.

On a related note, this Novena to Blessed Michael McGivney is circulating: