5

Sep

Sermon by Fr. Richard Cipolla given on Sept. 5, 2022

Today is the feast of St. Lawrence Justinian, the first patriarch of Venice, whose

life was marked by working for the reform of the clergy of his day in the

monastery of the Augustinian Canons near Venice of which he was a member.

Notice I said he worked for reform, worked. And today we celebrate Labor Day in

this country, which is a celebration of all the workers in this country whose

contributions in their jobs helped make this country great and prosperous.

But what is the origin of work according to the book of Genesis? It is the fall of

man. When God drives Adam and Even out of the Garden of Eden he tells Adam:

To the man he said: Because you listened to your wife

and ate from the tree about which I commanded you,

You shall not eat from it.

Cursed is the ground * because of you!

In toil you shall eat its yield all the days of your life. h

Thorns and thistles it shall bear for you,

and you shall eat the grass of the field.

By the sweat of your brow

you shall eat bread,

Until you return to the ground,

from which you were taken;

For you are dust,

and to dust you shall return. i

Not a good beginning for work. And yet God in his infinite mercy and love saw to

it that even the curse of work became transformed into something good and

positive in human life. It is true that for many people throughout human history

work has been toil and struggle that was a negative load on their humanity. But

when the concept of work is included and thereby transformed when St. Benedict,

the founder of monasticism in the West, conceived of the monastic life as ora et

labora: pray and work, the very idea and practice of work as human toil is

transformed and enriched. It is within the monastic movement that the very

concept of work is transformed from the punishment of Adam and Eve to the

possibility that work combined with prayer could be a vehicle for the

transformation of society, where the fruits of work could become a vehicle to show

the glory and love of God in the world.

It is no accident that there was a remarkable flourishing of art and music in the

centuries that followed the flourishing of the monastic movement. How wonderful

is it that the toil and thistles of Adam’s punishment becomes the deep beauty of

religious painting that spread throughout the Christian world and was taken even to

the New World where it flourished within the bosom of the Church and her faith?

And the same for the art of music whose roots are in the chant of the Mass. How

blest are we to hear this music at this Mass played and sung by volunteers who

take on this work for the glory of God?

We Catholics have much to be thankful for on this Labor Day. We know that work

will always bear some of the sheer toil that afflicted Adam. But we also know

from our own experience how our work in this life can be a source of great

happiness and beauty.

Our processional hymn we sang a short while ago, “Come, labor on, who dares

stand idle on the harvest plain”, tells us that when work is done in behalf of the

coming of the kingdom of God and when work is joined to the saving work of

Christ on the Cross it can be even a source of real joy. Take the printout of that

hymn home with you and ponder its words. Then you may understand how when

ora is joined with labora, even work becomes a source of joy and beauty.

5

Sep

Regina Pacis Academy will celebrate the opening of the school year with a Solemn Mass in honor of the Nativity of Our Lady on Thursday, September 8th at 9:15 am at St. Mary Church, Norwalk, CT.

The public is invited to attend.

St. Mary’s Church will also have a low Mass at 8 am.

5

Sep

5

Sep

31

Aug

The Roman Forum

31st Annual New York City Church History Program(2022-2023)

The Center Cannot Hold:A “Hermeneutic of Continuity”? Or “the Opiate of the Church”? (1978-2013)

Lecturer: John C. Rao, D. Phil. (Oxford University)Chairman, The Roman Forum

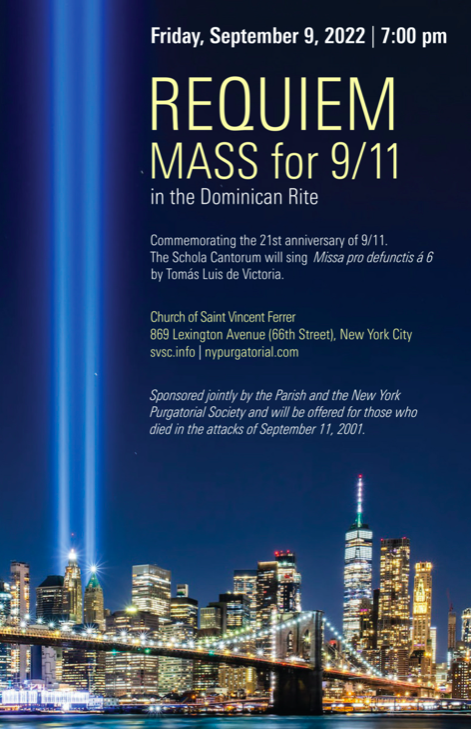

September 11: A Deeply Troubled Church in a Collapsing Postwar Order

September 25: Here Today—Gone Tomorrow

October 9: A Call for Help From “the Christ Among Nations”

October 16: Affirming the Faith—While Dismantling the Temple

November 13: Sailing to Byzantium on “the Opiate of the Popes”

November 20: The End of Soviet Communism and the New Liberation Theologies: Marxist, Neo-Liberal, and Neo-Conservative

December 11: The New World Order on Steroids

December 18: Our Future Lies in Our Past: Traditionalism—1978-1990s

January 8: The Year 2000—Ecumenism and Millenarianism

January 22: The Hermeneutici and the Conservative Dilemma

February 5: The New World Order’s Culture of Death

February 12: How Goes the Internal Mission?

February 26: How Goes the External Mission?

March 5: Habemus Papam!!

March 26: Did You Ever See a Dream Walking?

April 2: The Horror!! The Horror!!

April 16: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

May 7: My End is My Beginning

Sundays at 2:30 P.M, Most Holy Redeemer Church, East 3rd Street Between Avenues A & B

Wine & Cheese Reception: $15.00

N.B.— Audiotapes of all lectures will be posted on the Roman Forum Church History Lecture stream on SoundCloud.

31

Aug

Contact us

Register

- Registration is easy: send an e-mail to contact@sthughofcluny.org.

In addition to your e-mail address, you

may include your mailing addresss

and telephone number. We will add you

to the Society's contact list.

Search

Categories

- 2011 Conference on Summorum Pontifcum (5)

- Book Reviews (99)

- Catholic Traditionalism in the United States (25)

- Chartres pIlgrimage (17)

- Essays (179)

- Events (685)

- Film Review (7)

- Making all Things New (44)

- Martin Mosebach (35)

- Masses (1,362)

- Mr. Screwtape (46)

- Obituaries (19)

- On the Trail of the Holy Roman Empire (24)

- Photos (350)

- Pilgrimage Summorum Pontificum 2021 (7)

- Pilgrimage Summorum Pontificum 2022 (6)

- Pilgrimage Summorum Pontificum 2023 (4)

- Sermons (79)

- St. Mary's Holy Week 2019 (10)

- St. Mary's Holy Week 2022 (7)

- St. Mary's Holy Week 2023 (7)

- St. Mary's Holy Week 2024 (6)

- Summorum Pontificum Pilgrimage 2024 (2)

- Summorum Pontificum Pilgrimage 2025 (7)

- The Churches of New York (199)

- Traditionis Custodes (50)

- Uncategorized (1,391)

- Website Highlights (15)

Churches of New York

Holy Roman Empire

Website Highlights

Archives

[powr-hit-counter label="2775648"]