7

Feb

7

Feb

27

Jan

St. Mary Church, Norwalk, CT, Solemn Mass, 7 pm

Sts. Cyril and Methodius Oratory, Bridgeport, CT, 6 pm: Blessing of candles, procession and high Mass.

St. Emery, Fairfield, CT, 6 pm, blessing of candles, procession and Solemn Mass.

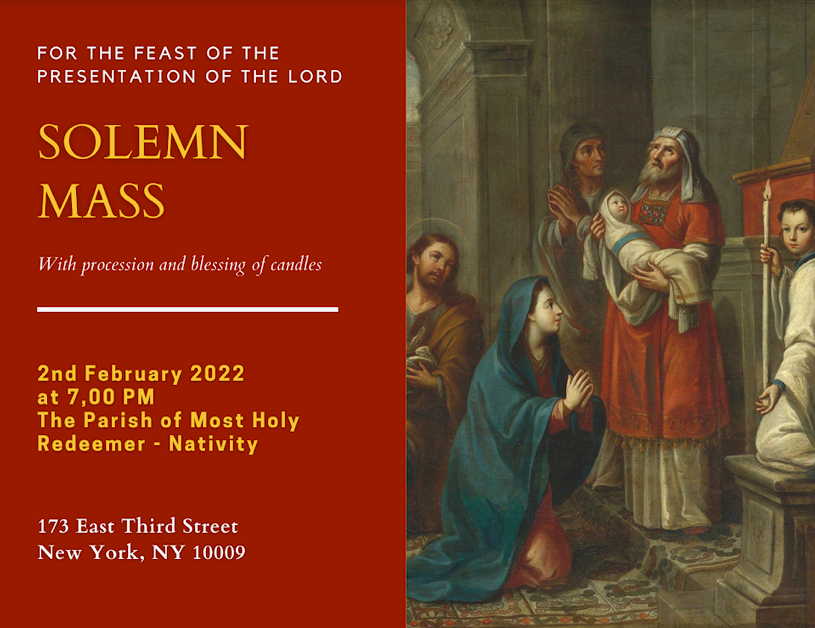

Church of the Most Holy Redeemer, New York, NY, 7 pm, Solemn Mass with blessing of candles and procession

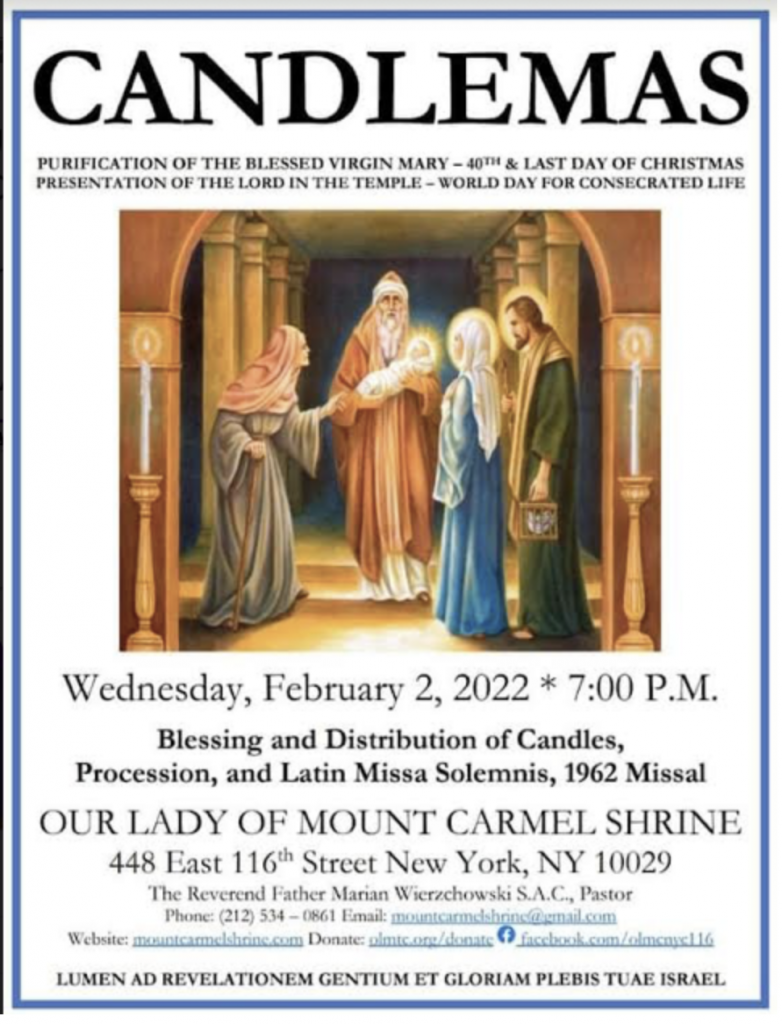

Our Lady of Mount Carmel, New York, NY, 7 pm, Solemn Mass, blessing of candles and procession

Immaculate Conception, Sleepy Hollow, NY, low Mass 7 pm,

The liturgy will start with the blessing of candles, but there will be no procession. Please bring your own candles, if you would like them to be blessed.

Sacred Heart Church, Esopus, NY, Low Mass, February 2, 2022 at 11:00 a.m.

Holy Trinity Church, Poughkeepsie, NY, Missa Cantata, February 2, 2022 at 7:00 p.m.

Church of St Mary / St Andrew, Ellenville, NY, Missa Cantata, February 2, 2022 at 7:00 p.m.

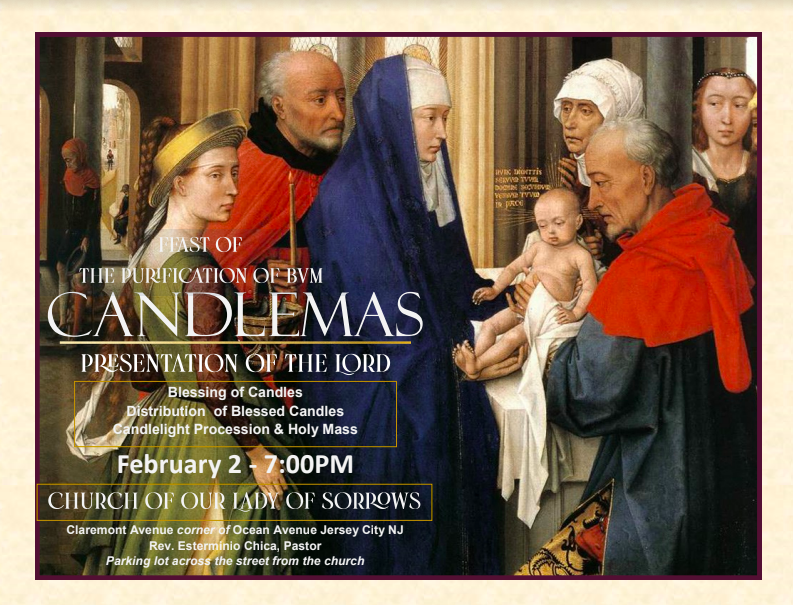

Our Lady of Sorrows, Jersey City, blessing of candles, procession and Mass, 7 pm (Bring your candles, labled with your name, to be blessed)

Shrine Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament, Raritan, NJ, 7 pm, blessing of candles and procession, Missa Cantata.

26

Jan

Silent Retreat on Long Island

Posted by Stuart ChessmanSilent Retreat on Long Island directed by Fr. Donald Kloster

Adults, ages 18-39

Friday February 4th arrival after 5 pm to Sunday morning

Friday: 6 pm to 10:45 pm adoration

Saturday: 9:30 am to 10:45 pm adoration; 20 minute meeting for everyone with Fr. Kloster for Confession and/or spiritual direction; low Mass at 10 am in the presence of the Blessed Sacrament

Sunday: low Mass at 8 am followed by brunch

Immaculate Conception Seminary, 440 West Neck Road, Huntington, NY

Contact: Alexandra Lynch, catholicywhv@gmail.com

23

Jan

Epiphany III 2022

Sermon by Fr. Richard G. Cipolla

Last week at Mass we heard the gospel from St. John that recounts Jesus’ first miracle, the changing of water into wine. Today on the Third Sunday after the Epiphany we hear of two more miracles performed by our Lord: the healing of the lepers and the healing of the centurion’s servant. The gospels in the season of the Sundays after Epiphany concentrate on the miracles of Jesus as the answer to the seminal, the basic question asked and answered in the gospels: who is this man Jesus? These miracles are not offered as proof to the gospel answer to this question, that he is the Son of God, the Word of God the Savior of the world. But they are offered—and they are offered in a historical sense, not in some sort of symbolic sense—to point to the answer to the seminal question. Many who call themselves Christians have been having problems with these miracles for a long time, and they have done so because they have succumbed well over a century ago to a rationalistic and moralistic understanding of the person of Jesus Christ. And they are locked into a totally outdated and false understanding of the physical world: they live in an imaginary Newtonian world in which surprise is absent. It is absent by decree, since there can be no surprises in a clock world understanding of the physical universe. One does not have to be conversant with the ins and outs of contemporary physics to know that physical reality is full of surprises and that these surprises happen with alarming frequency. The irony is that in an age in which science is seen to be the basis and the touchstone of what is real, most people, certainly including theologians, are locked into a view of reality that corresponds in no way to the mysterious and in a way crazy picture of physical reality that contemporary physics paints for us. And the verb paints is very apt, for physical reality is much more like a painting whose meaning can never be fully grasped than the rather boring view of reality that is like a Patek Phillipe watch: expensive, keeps good time, but in the end not very interesting.

There is no doubt that we are living through one of the worst crises the Church has faced in her now more than 2000 year history. The roots of this crisis do not lie in yesterday. The roots have been growing for at least three centuries, some would say much longer than that, and these roots are firmly grounded in the soil of that radical and myopic view of reality that places the individual at the center of the universe and as the ultimate meaning of what is real and true and good. The cry of Martin Luther: “Here I stand, I can do no other”, finds its logical and inevitable consummation in the world in which we live, a world that loves to talk about community only in terms of a reality that is totally circumscribed by a radical denial of what has formed communities in the past: family, friends, shared values grounded in something beyond the community, in a sense of the transcendent. This is a world in which any objectivity in morality is denied. Morality is defined in terms of the freedom of the individual to do whatever he or she wants, with the exception of hurting another person, and that hurting another person is seen in terms of making that other person unhappy. Even killing another person does not get in the way of this morality based on the self and a selfish understand of freedom, as we can see in the painful example of the contemporary acceptance of abortion as a personal right.

The crisis in the Church lies in her willful refusal, in those who are supposed to be the guardians of the Faith, to vigorously counter in an ecclesial way, that is, based on the truth of the Gospel, this warped view of what is real, what is true and good. There is no doubt from a reading of Church history that the Church has succumbed at various times in her history to trying to make peace with the world by a deliberate forgetting of her role and mission given to her by Him who is the ultimate contradiction to the world. But in those times, there have always been those whom we call saints, especially the martyrs, who have seen through these dishonest attempts to come to terms with the world, and whose lives and death have the same effect as Jesus’ miracles: they point beyond and above to the God who is good, true and beautiful. The Church has often had a hard time dealing with these people: like St Antony of Egypt who fled from the world to live in the desert; like St Francis of Assisi who embraced a terrible form of poverty to point to the reality of the radical nature of Christianity; like St Thérèse of Lisieux, whose understanding of the vocation of love that lies at the heart of what it means to be a Catholic brought her to such terrible suffering and in the end at her death a darkness that she perceived as a loss of faith. Or like St Thomas More, that very worldly and intelligent man, that eminent scholar and writer of superb even if mock Ciceronian Latin, that ambitious man who rose so high in political power and who found himself quite unexpectedly and not by choice confronting that choice that is at the heart of the Catholic faith and yet is denied by most Catholics, that choice between the world that tolerates only a tamed and impotent Christian faith, and that faith which demands to choose contra mundum because of love of Christ who diedpro mundo. And Thomas More chose for God in the context of defending the Papacy in the person of a Pope who was no great model for the Petrine ministry. The trouble is that these saints and most saints have been so pietized and hagiized and sentimentalized by Catholics that their meaning, who they really were, has evaporated. St Francis becomes a Disney character complete with birds and a birdbath. St Thérèse becomes a sweet pious French little girl holding roses. St Thomas More becomes a character in a Robert Bolt play who is reduced to a man of principle.

But this is all part of the history that has brought us to this time of crisis:. A time when bishops refuse to condemn the warped worldliness of their flock holding prominent positions in government, those who dare to claim to be followers of Jesus Christ, dare to proclaim themselves as Catholics, dare to claim to be daily Mass goers, and at the same time support contemporary moral positions that deny the Lord of life himself. And all of this in the name of compassion, compassion redefined in the name of the freedom of the individual. And this is what compassion has been reduced to. So many Catholics do not know what compassion means: it means to suffer with another. It does not mean to excuse the faults of another. But it does mean to love the other, and to love some one means to be willing to suffer with that person, means to reach out to the other from the Cross of Jesus Christ: there is no other compassion that the compassion of Mary at the foot of the Cross. There is no other compassion than St Francis’ receiving the stigmata. There is no other compassion than St Thérèse suffering her dark death in the context of her vocation to love. There is no compassion other than St Thomas More’s terrible realization of what love for the world really means, dying in behalf of the love of Christ for all men, in a most ambiguous context. It means that there is no foundation for true compassion except in the infinite compassion of Jesus Christ for the sinners of the world.

But what has brought us to the particular depth of crisis the Church faces today? The difference between the crises of the Church in the past, and there were many of them, and the crisis besetting us now is this: the contemporary loss of the sacred, specifically the loss of the liturgy, of the Mass, as the binding force that was the fundamental context in which the Catholic life was lived through the centuries. It was, in the words of the Second Vatican Council, the fons et culmen, the source and summit of the Catholic life. The Mass of the Tradition, the Traditional Roman Mass, is the fruit of organic development whose words, prayers, gestures, music cannot be identified with any one culture, any one provenance. The Mass includes its roots in Judaism, in the Greek speaking world of ancient times, in the Middle East of Syria and Lebanon, in the city and empire of Rome, drawing from traditions far and wide, from Britain to Gallican France, to Spain, to North Africa, from what we call in general the East: all expressed in a common and unchangeable language that is foundational in the Christian world of the West. This structure, this palace, this humble home, this house that everyone, rich, poor, men, women, children,,educated, peasant could come to and be at home in, at home even if not intellectually understanding what all these rooms meant, coming into a place that was familiar and yet not common, the place that was always there, that did not depend on the fashion of the world, what was au courant at the time, that transcended time and space, that always pointed to what one could not understand but believed. This is so wonderfully captured in that scene in Graham Green’s novel, The Power and the Glory when the Mexican peasants sigh with happiness as the priest, risking his life for them, says the Mass in a poor home, and when he raises the Host they sigh, and in that sigh they know, they know, despite the terrible reality of their lives, they know that God is with them again in the home of the Mass.

And yet, what we are doing right now is the antidote to the crisis we face. We offer at this time and in this church that Mass that grew organically through 1500 years, not as a set of prayers and rules but as a living organism that took was best in the ever changing historical milieu of the past millennium and a half, the form of the Mass inculturated by and in the many cultural milieus of the past 1500 years, shedding what was dross and embracing what was consonant with the essence of the Roman Mass, at whose heart is the re-presentation of the Sacrifice of the Cross and thus a source of grace. Pope Benedict’s Summorum Pontificum did not “allow” the free celebration of the Traditional Roman Mass. That document broke the spell of the false and un-Catholic fiction that St. Paul VI had abrogated the Traditional Roman Mass in his attempt to impose the Novus Ordo form of Mass on the whole Church. How could a form of the Mass that was written by a committee whose members used liturgical scholarship for their own purposes and who were determined to make up a liturgy that would appeal to “modern man”, a liturgy that is fixed in one time and space, and which is the product not of organic growth but rather of doctrinaire imposition of attitudes of a very small time in the history of the Church: how could this form of the Mass be continuous with the Traditional Roman Mass?

The Consilium that produced the Novus Ordo Mass forgot that the Mass is for God, is the worship of God. It is not for the priest nor for the people.

The Mass is not a religious exercise for people. It is not something for the priest to make up and to make relevant and to make people happy. It is not an extension of religious education, a didactic exercise. The Mass is where one enters into the Holy of Holies and gives oneself over to the mystery and love of God. When I was ordained a priest nearly 38 years ago, I never dreamed I would be celebrating this Mass in this place surrounded by people of faith from all sorts and conditions of men and women. But God is good and faithful. And he will continue to be faithful despite those who presume to outlaw this form of worship that is the product of and the heart of Catholic Tradition. And we rejoice in this source of grace and truth, this treasure, the ultimate treasure that is filled with the beauty of God in the distillation of time of that time impregnated with the astounding event of God becoming man, becoming flesh of a real woman who lived full of grace at a specific time and place in the history of the world. And what else can we do on this day then to be grateful and happy, oh so happy, oh so filled with joy? And what else can we do than before Holy Communion to echo the centurion’s words from the Gospel: “Lord, I am not worthy that you should enter under my roof, but only say the word, and my soul shall be healed.”

22

Jan

A Solemn Requiem Mass and Burial were celebrated today for Alice von Hildebrand at Holy Family Church in New Rochelle.

19

Jan

From the internet presence of the “German Catholic Church.”

“The implementation rules in the form of Responsa ad Dubia, issued by the Congregation for Divine Worship with the approval of the Pope, which regulate even parish bulletins (“it is inappropriate to include such a celebration in the parish’s order of divine services”) are the opposite of subsidiarity.”

Dass die von der Liturgiekongregation mit Zustimmung des Papstes in Form von Responsa ad Dubia erlassenen Ausführungsbestimmungenbis hinein in Pfarrblätter regeln (es sei “nicht angemessen, eine solche Feier in die Gottesdienstordnung der Gemeinde aufzunehmen”), ist das Gegenteil von Subsidiarität.

Naumann, Felix, “Der Papst hat die heilsame Dezentralisierung aufgegeben” in Katholisch.de, 1/18/2022

UPDATE (also on ‘subsidiarity’):

Criticism from a Pope Francis appointee at the Order of Malta:

The Grand Chancellor of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta has said that a new Vatican-drafted constitution is a “hazard” to the order’s sovereignty and announced he is stepping down from coordinating the constitutional reform process.

“Vatican reforms are ‘hazard’ to sovereignty, says Order of Malta Grand Chancellor,” The Pillar, 1/19/2022

Centuries of diplomatic independence for the Sovereign Military Order of Malta could come to an end if a new Vatican-drafted constitution for the order is put into effect. The new constitution could see the religious order lose its permanent observer status at the United Nations, and would imperil its bilateral diplomatic ties.

The new constitution, which would explicitly define the order as a “subject” of the Holy See, would end nearly a millennia of sovereign independence for the religious order, have sweeping implications for its diplomatic relationships with more than 100 nations and the United Nations, and impact its humanitarian work around the globe.

“Order of Malta would be ‘subject’ of Holy See under new Constitution,” The Pillar, 1/14/2022

18

Jan

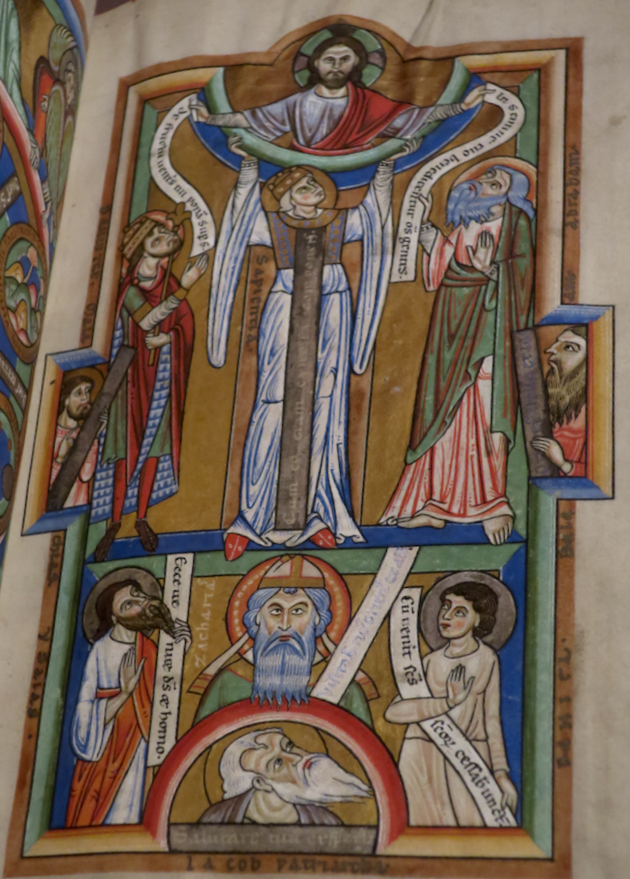

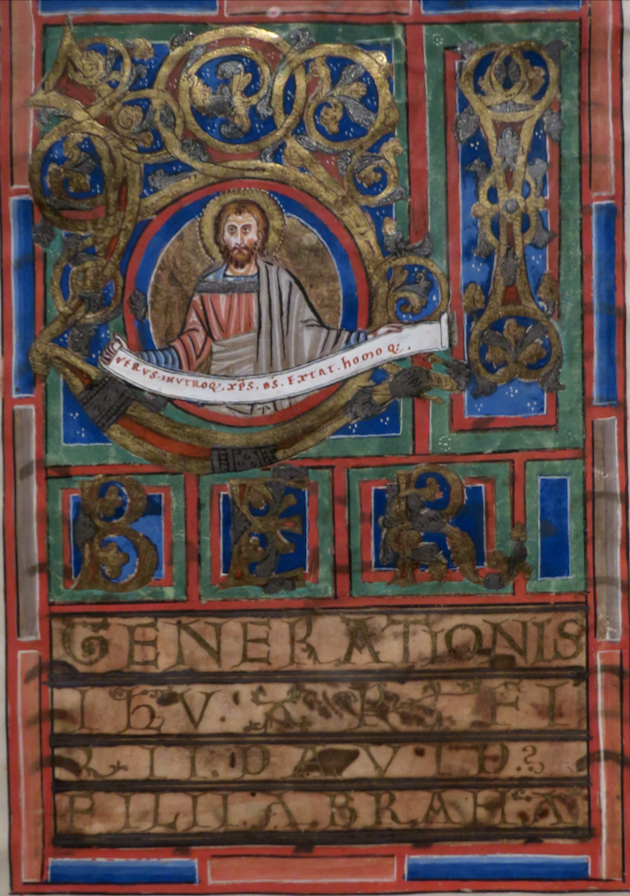

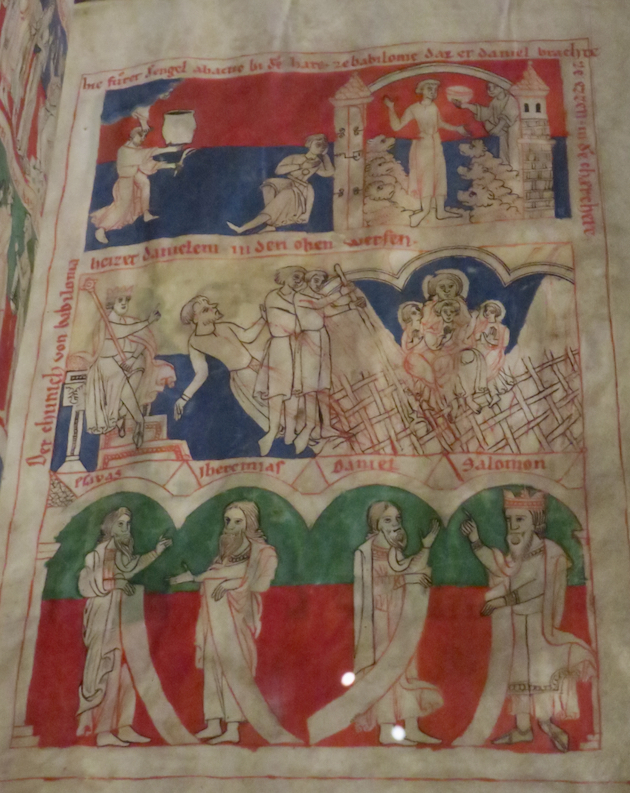

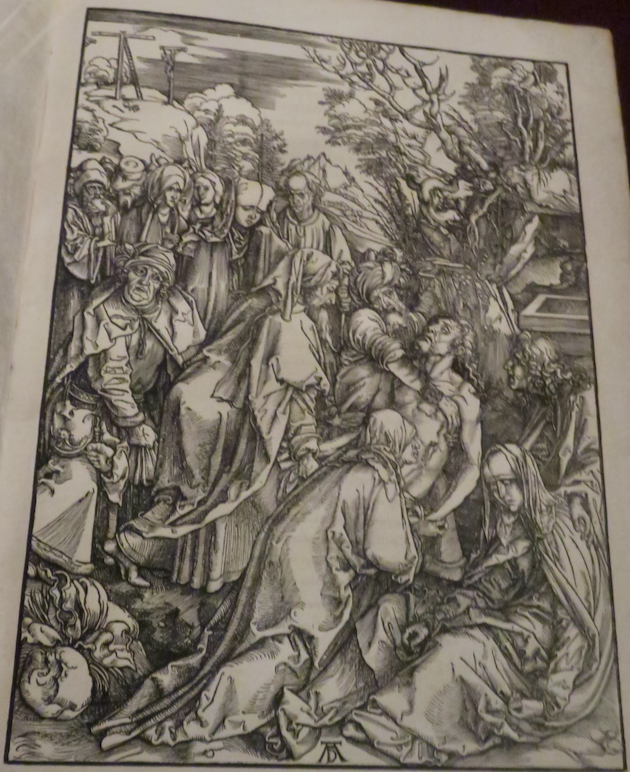

Imperial Splendor

Posted by Stuart Chessman

The Art of the Book in the Holy Roman Empire 800-1500

Exhibition at the Pierpont Morgan Library (through January 23)

The Holy Roman Empire, despite many ups and downs, was a key force in European art, culture and politics between 800 and 1806. This exhibition basically covers seven centuries of book illumination in the empire from 800 to 1500. The exhibition focuses on the Holy Roman Empire as it existed around 1500, minus the Netherlands – in other words, Germany and German cultural areas. This way the exhibition achieves cultural and national unity. For to cover all the territories under the domination of the empire at its greatest extent – by adding the northern Netherlands, eastern France, and North /Central Italy – would make the exhibition a general history of Christian European culture. It is impressive that the exhibits are drawn mainly from the holdings of the Pierpont Morgan library itself, as supplemented by loans from other American institutions.

The exhibition also serves as a good course in the political development of the empire. At first, the Holy Roman emperors themselves played a dominant role in patronage, commissioning works from monasteries and major ecclesiastical centers. This was gradually supplemented and succeeded by the growing patronage of the nobility and the princes. In the 14th century the first real permanent capital of the empire was established in Prague, in the face of growing rivalry with Vienna and the Hapsburgs of Austria. Finally, at the end of medieval times, came the flourishing of the great imperial cities – Nuremberg, Augsburg, Strassburg – as producers of art. Naturally there was much overlap: Emperor Maximilian I, who died in 1519, was one of the greatest patrons of all and the ecclesiastical center of Mainz – which never quite became a free imperial city – played a major role around 1450. Indeed, on display in this exhibition is a Gutenberg Bible (the Morgan Library has three!) printed in the same city of Mainz -using a technology that in the course of time would end the illuminated manuscript tradition.

The art on display consists primarily of illuminated manuscripts as well as book covers and liturgical vessels in precious metal. Now one must understand that in the first centuries covered by this exhibition (800 to 1200) the so-called “fine arts” of architecture, painting and sculpture were not perceived as superior to “applied arts” like book illumination or goldsmiths work. Just as much care was given to the precious book covers, liturgical vessels, reliquaries – as well as to the manuscripts – as was given to the churches that contained them. In other words, what we see in this exhibition are the main products of the art of these early medieval periods.

We see also a transformation of the role of the artist, his art and his patron. In the first centuries lavish illustrated manuscripts are encased in gold covers. These are primarily commissions by the imperial family themselves and the artists are primarily monks at the major monasteries. Later, monasteries and noble families joined the imperial families as major patrons of art. From the 13th century onward lay professional artists played an increasing role in illustrating manuscripts. By the 15th century professional artists had become the dominant force in free cities like Nuremberg and an export trade came into existence. A growing interaction developed between book illumination and the new art of printing. Finally, we see the artists of the Renaissance – like Albrecht Dürer – bringing their individual creativity to bear in exploring entirely new approaches to traditional themes.

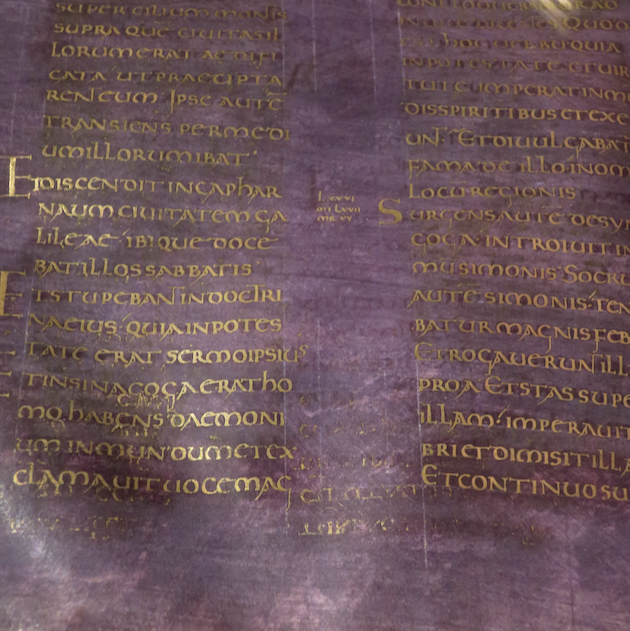

Do not these masterworks demonstrate to us the importance the written word once had? Today a word appears on Outlook and – if it even survives the spell checker – shortly thereafter may vanish forever. Yet in illuminated manuscripts the word is carefully preserved for all time. This is particularly true of the early medieval period. But even towards the end of the centuries covered by this exhibition, we see the extreme care with which books, both printed and handwritten, are prepared. We see also the cultural importance of Latin – the language of most of the manuscripts in this exhibition. Throughout seven centuries it served as a unifying factor – and of course was always the Church’s liturgical language. After 1200, books written in the vernacular (German) start to appear – and in the 15th century we find one Czech example. Yet Latin retained its primacy throughout.

It may be obvious, but I still need to point out that in all the seven centuries covered by this exhibition, the Catholic Church was the overwhelmingly dominant artistic force of the “Holy” Roman Empire. In the later centuries secular works do increasingly appear but were often Christian allegorical or philosophical treatises. From the end of the Carolingian age to the Renaissance, artists interacted with the same elements of Christian belief: the Old and New Testaments, the lives of the Saints, edifying parables and allegories. The Morgan exhibition does point out the Christian meaning of many of the images and symbols of the objects on display and the role of certain items in church ritual (e.g., processional gospel books, large format books of chant).

The works these artists created over so many centuries of course show great stylistic differences and even artistic development; the Christian intellectual foundation, however, remained the same. One also cannot speak of “progress” – is a Dürer print superior to an Ottonian illumination? This is the nature of Western traditional art, which modernists – either in art or liturgy – cannot understand: the tradition remains the same even if each age makes its own contribution in creative dialogue with the permanent elements of the culture.

The visitor can experience this unity first hand today if, proceeding beyond the timeframe of this exhibition, he visits the cities and monasteries where the books presented at the Morgan Library were created. Such as the immense baroque monastery of Weingarten in south-west Germany. Or St. Gallen – now infamous – which was built later and is more restrained, but has an incomparable library. Only Reichenau preserves somewhat the appearance of the abbey buildings as they existed when the magnificent manuscripts in this exhibition were created in Ottonian times. The city of Regensburg perhaps most perfectly illustrates this continuity – with sacred edifices dating from the 8th to the 18th centuries. The Holy Roman Empire – or at least parts of it – remained true to its Christian Mission even to the end of the 18th century.

It is this diversity in unity which distinguishes the art of the West – at least before 1800. The Holy Roman Empire was preeminently representative of such a culture, lacking as it did strong central political institutions throughout most of its existence. But this “Holy” Empire always had one clear focus of unity: Christianity. This exhibition brilliantly showcases just one example of this empire’s cultural achievements.

The Lindau Gospels with precious covers from the second half of the 9th century (front, above) and the second half of the 8th century (below).

(Above) Cover of Mondsee Gospels, Regensburg, 11th Century)

(Above) Gospels written on purple parchment wth gold ink, in imitation of late Roman work (Trier, 9th century).

(Above and below) Chalice and paten from St. Trudpert monastery, near Freiburg, Germany. (around 1230-1250)

(Above) This manuscript may have belonged to St. Hedwig of Silesia. (Early 13th Century)

(Above) Patronage by the nobility. (around 1247)

(Above) Celebration of the Mass – along with humorous animal scenes.

(Above) This illumination shows the influence of the revelations of St. Birgitta ( the Virgin Mary adoring the Christ Child Who is bathed in radiant light) (Prague, around 1405)

A new age dawns: (Above) a print from the Passion by Albrecht Dürer (Below) An illumination in the style of contemporary Nuremberg art .

17

Jan

17

Jan

Contact us

Register

- Registration is easy: send an e-mail to contact@sthughofcluny.org.

In addition to your e-mail address, you

may include your mailing addresss

and telephone number. We will add you

to the Society's contact list.

Search

Categories

- 2011 Conference on Summorum Pontifcum (5)

- Book Reviews (98)

- Catholic Traditionalism in the United States (24)

- Chartres pIlgrimage (17)

- Essays (178)

- Events (680)

- Film Review (7)

- Making all Things New (44)

- Martin Mosebach (35)

- Masses (1,356)

- Mr. Screwtape (46)

- Obituaries (18)

- On the Trail of the Holy Roman Empire (23)

- Photos (349)

- Pilgrimage Summorum Pontificum 2021 (7)

- Pilgrimage Summorum Pontificum 2022 (6)

- Pilgrimage Summorum Pontificum 2023 (4)

- Sermons (79)

- St. Mary's Holy Week 2019 (10)

- St. Mary's Holy Week 2022 (7)

- St. Mary's Holy Week 2023 (7)

- St. Mary's Holy Week 2024 (6)

- Summorum Pontificum Pilgrimage 2024 (2)

- Summorum Pontificum Pilgrimage 2025 (7)

- The Churches of New York (199)

- Traditionis Custodes (49)

- Uncategorized (1,385)

- Website Highlights (15)

Churches of New York

Holy Roman Empire

Website Highlights

Archives

[powr-hit-counter label="2775648"]