23

May

23

May

Happy Pentecost!

Posted by Stuart Chessman

The peony is known as the Pfingstrose (Pentecost Rose) in German. For it blooms around the time of Pentecost – and its red blossoms match the liturgical colors of the day. This year, at least in the vicinity of New York, it has bloomed right on schedule.

22

May

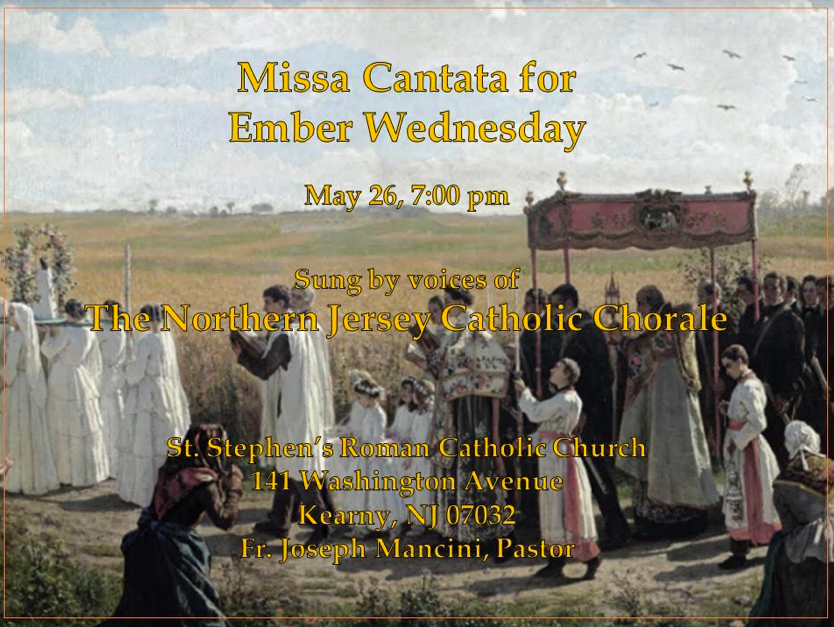

Ember Wednesday in Kearny, NJ

Posted by Stuart Chessman21

May

There will be a Solemn High Mass at the Merchant Marine Academy on Saturday June 5, 2021, King’s Point, NY at 10:00 am for the Feast of St. Boniface, Apostle of Germany.

Fr. Donald Kloster, Celebrant, Fr. Michael Novajosky Priest Deacon, Fr. Sean Connolly Priest Subdeacon, Mr. Bill Riccio, Master of Ceremony.

Mr. David Hughes, Mr. David Indyk, and the Viri Galilaei will chant the Mass.

20

May

Saturday, May 22, the Vigil of Pentecost

For the Vigil of the Pentecost, on Saturday May 22, Sts. Cyril and Methodius in Bridgeport, CT will offer a high Mass at 9 am, including the Prophecies, blessing of the font and Mass.

St. Patrick Oratory in Waterbury, Ct will follow the same schedule: at 9 am, the Prophecies, blessing of the font and a high Mass.

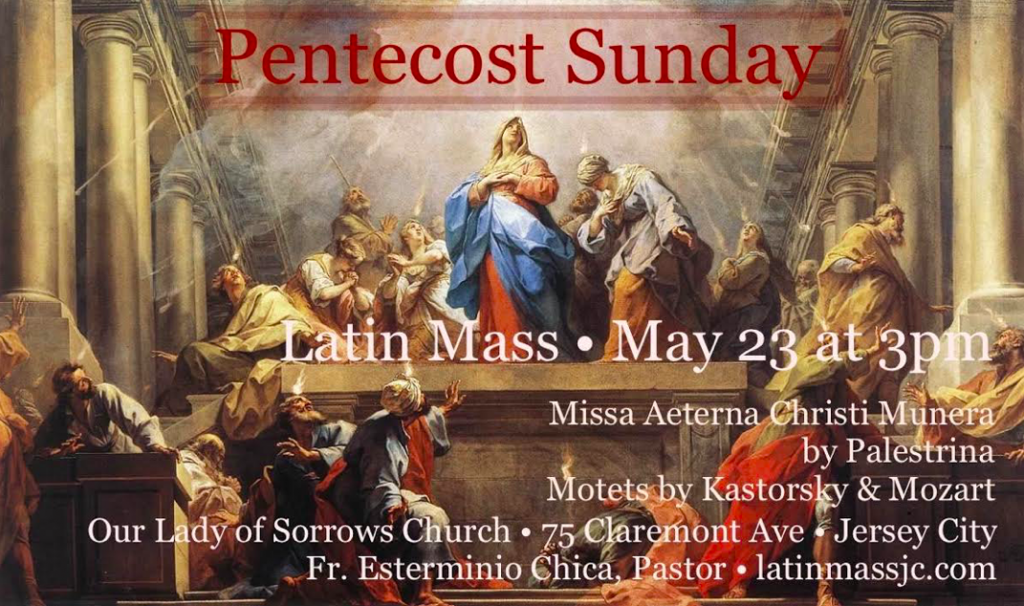

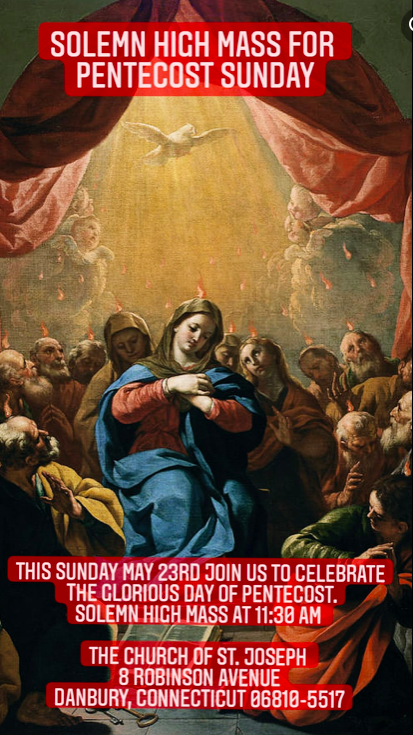

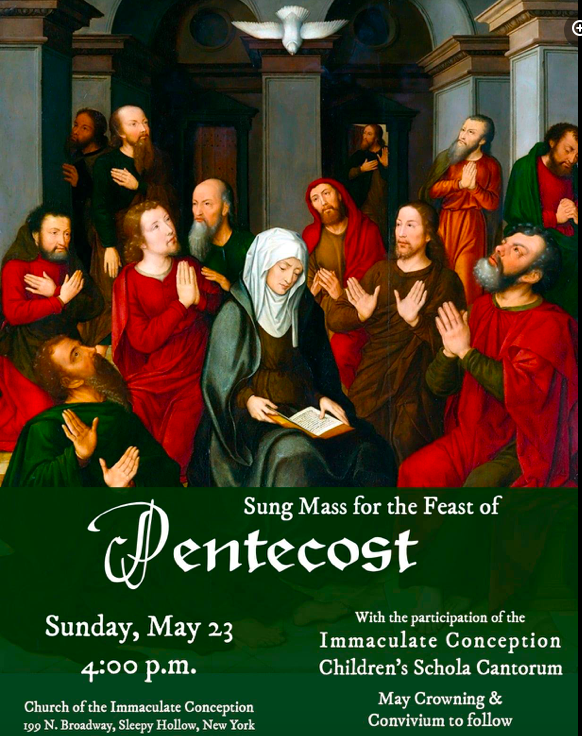

Pentecost Sunday, May 23

19

May

18

May

It’s eight years into the pontificate of Pope Francis. I’d like to take stock once again of where American Catholic Traditionalism stands. But before dealing with Traditionalism, I need to set the stage by outlining the historical situation in which we find ourselves. Because the Catholic Traditionalist movement does not exist in a vacuum. It is situated – especially after Summorum Pontificum – in the greater Catholic Church, both of the United States and of the world. And that Catholic Church finds itself in a specific historical context.

Speaking of the larger society, the United States-led Western world has undeniably reached a crossroads. The turmoil of the last few years has scarred the country: the coronavirus shock, the political agitation and violence on the streets and five years of virtual civil war between President Donald Trump and the American establishment. Within the United States, the forces of the establishment – the so-called deep state, civil society or “power elite” – have shifted easily into an overtly totalitarian mode of operation. In the wake of the coronavirus, the government assumed the right to regulate the most intimate details of the life of its citizens even within the walls of their own homes. Throughout the educational system and business enterprises those who merely refrained from endorsing – let alone challenged or questioned – the emerging orthodoxies were blacklisted and suspended or fired from their positions. And all too often the victims then confessed their culpability themselves, very much in the style of the Moscow show trials. Censorship of social media has become virtually official practice, Finally, we witnessed the Reichstag Fire of January’s events on Capitol Hill.

During all of this, Americans – or rather a large percentage of them – were gripped by a rising tide of fear and hysteria, fostered by the news media. People are afraid of many things; the coronavirus, domestic violence and disorders, economic disaster. One sees this in the fearful actions of those hiding because of the risk of contagion or who grow confrontational regarding preserving social distance or wearing a mask. The Biden presidency was in part sold on the deceptive promise of a return to normalcy. We are already seeing how unlikely that’s going to be – just on the international front, fresh crises are already forming. The American establishment has prevailed so far, yet its triumphs already seem like a pyrrhic victory.

The American Catholic has become in many respects the proverbial man without a country. The United States, where his parents and grandparents were so happy to “fit in,” now describes itself as “systemically racist.” The institutions that this Catholic “man in the street” had been taught to revere, rightly or wrongly – like the great universities, the military, the major corporations, the police – are all now completely indifferent if not downright hostile to him. Moreover, is he not told frequently that his Christian faith itself is a problem? – witness the fate of previously revered monuments to Catholic heroes or the ongoing campaign to purge every reference to Christianity from the public discourse. The governing progressive powers remain militantly opposed to all the social and moral doctrines that the Church had previously encouraged the laity to advocate ”in the public square.” But, marginalized by secular society, the Catholic finds his home in his own Church crumbling as well. In the Coronavirus panic, the Catholic laity have been restricted or prohibited from attending Mass, receiving the sacraments and even stopping into church for prayer. Indeed, the laity had been largely dispensed from any requirements associated with these practices anyway.

This exclusion of Catholics from the new American mainstream of course also applies to the institutional Church as well. The Catholic Church has performed abysmally in these trying times. The bishops have accepted without protest the closing of their churches and schools, the suspension of the sacraments, the reduction of Catholic life to a primarily “virtual” affair. The bishops and clergy have even at times exceeded the requirements of the state. At no time in the past have the bishops imposed rules regarding the liturgy as stringent – and drastically enforced – as the lockdown regulations they universally enacted. In the face of the rise in political violence, the bishops sought to straddle the fence, cautiously endorsing protesters who overthrew statues of Catholic heroes of yore like Columbus or Junipero Serra.

Meanwhile, the crisis generated by the sexual abuse scandals – with its adverse press coverage, financial damage and diocesan bankruptcies – continues to fester with no end in sight. The same is true for the endless series of closings of parishes, schools and seminaries. The Church continues to be unable to recruit sufficient priests, brother and sisters to maintain its institutional presence. The impact of the Catholic Church on public policy, thought and culture is nonexistent – unless, of course, like Pope Francis, it is endorsing the agenda of the secular establishment

The culmination of all these trends is the coronation by the media of President Joe Biden as a “devout” Catholic – seemingly because he has so explicitly rejected non-negotiable moral positions of the Catholic Church. While President Biden continues to implement his stated commitment in support of abortion, the American bishops have not yet been able to formulate any response. The Vatican and the Pope’s most obsequious followers among the American bishops are actively working to block or delay any attempt to draw consequences from the conflict between Biden’s agenda and the principles the bishops had previously advocated(at least, in the case of most of them, on paper). This futility in dealing with such a prominent issue only confirms once again the lack of leadership, conformism and pusillanimity of establishment Catholicism in the United States.

The result of all this is most likely an accelerating disassociation of the laity from the institutional Church. Estimates indicate that, once the coronavirus restrictions end, a substantial part of the laity may never return to the public practice of the faith. That threatens to be life-threatening for the American Church, given that the continued vitality – and funding – of American Catholicism rests largely on habits of conformity inherited ultimately from the pre-Conciliar era,

In contrast to prior decades there is no possibility of turning to Rome. For the pope is as committed to the secular agenda of the Western establishment as the most radical American Catholic progressives. He has assumed – at least in appearance – an attitude of indifference to “life issues” and has expressed disdain for “culture warriors.“ But Francis’s own situation is not good. A cult of personality around Francis continues to be fostered without generating any real support in popular sentiment. Continued scandals in the Vatican, aggressive progressive agitation (especially in Germany), and ever-increasing financial difficulties foretell a dire future for the central administration of the Church. Meanwhile, the unending steam of actions and statements of the pope in areas such as marriage, homosexuality, environmentalism and secular politics will, in the long term, undoubtedly undermine the credibility of the Catholic Church as a spiritual force.

Does it not seem like an eerie return of the political and ecclesiastical chaos of the 1960s? The immediate practical effects on the life of the American Church, however, could not be more different. In many respects, Francis has simply ratified existing practices or abuses, not broken new ground. At least in the New York area, only the growing official recognition of the LGBT movement by the New York archdiocese represents a new, post-Francis development. Unlike his predecessor 55 years ago, Francis has not set off a revolutionary destructive wave within parishes, religious orders and educational institutions. To some extent, of course, this is because those institutions have by now been largely destroyed or secularized. We could also say that the earlier reverence for the centralized authority of the Church among the laity has also largely dissipated. In fact, those forces that Francis scorns – the pro-life movement, the Catholic Conservatives 1) and of course the Traditionalists – have largely continued on their accustomed path regardless of either what the Pope says or what is happening in secular politics.

For Catholic Conservatism the era of Francis – now merging with the age of Biden – has been particularly traumatic. For the Catholic hierarchy has all but officially adopted the seamless garment ideology crafted by the Catholic progressives years ago and so disputed by the conservatives. The progressive forces themselves now go much further and border on expressly advocating the complete abandonment of the pro-life cause.

No faction within Catholicism set as much store on the papacy as did the Catholic Conservatives. And now this same papacy has explicitly rejected everything the Catholic Conservatives stood for: the political alliance with Evangelicals, abortion as a paramount issue, the defense of capitalism and the support of American intervention throughout the world. Furthermore it is very clear that attempts to cooperate with the hierarchy in revitalizing Catholicism in seminaries and parishes are making little or no progress. The favored organizational form of Conservative Catholic apostolates – an unstructured “movement“ dominated by a charismatic authoritarian figure – has also led again and again to embarrassment and failure.

Yet the reaction of the Catholic Conservatives, except in some rare cases, has not been to go over to the camp of the enemy. They may have been abandoned by the Pope and disappointed by the lukewarmness of the Catholic hierarchy but they will not, just because of this, abandon their pro-life positions or their other historic causes. The pro-life movement, for example, remains active and continues its political advocacy, most often working with political leaders aligned with the Trump, populist wing of the Republican party.

Many of the most outspoken representatives of conservative Catholicism were unable to repudiate their principles and jump on the Francis bandwagon. They have developed into outspoken critics of the one or other aspect of the Catholic Church today. This resilience in the face of papal and hierarchical indifference or hostility is largely due to the greatly expanded network of Catholic media – especially social media. There is a vast array of sources – mostly online – available for those who wish to inform themselves about the Church today better. We could mention, among others, the Catholic News Agency, the National Catholic Register, LifeSiteNews, the new Pillar.com, Crisis, Catholic Culture aa well as a whole army of blogs. Finally, going beyond reporting and commenting on daily events, there is the revitalized First Things which has moved away from its original neoconservative ideology. All of this makes available to the Catholic who wants it a mass of information and articulate, critical commentary. We can understand the fury of the advocates of Francis confronted by this new reality and their constant talk about regulating or censoring the Catholic online presence.

The Conservative Catholics have redoubled their commitment to creating new practical apostolates – which, after all, has always been the thing they do best. The actions of FOCUS and certain other Catholic campus ministries are one of the few bright spots in today’s Church – an amazing contrast to the dreadful situation prevailing on the campus in the 1970’s – 1980’s. A new Catholic residential community is organizing in Texas, resembling Ave Maria village in Florida – even if its structure features a superabundance of apostolic organizations in relation to its size. Surprisingly, even in secular academia advocates for Catholicism are standing up. We have the intellectual movement of integralism dealing with Catholic concepts of Church/state relations – led by, among others, a professor at Harvard. More recently, a society dedicated to reexamining and recovering Catholic philosophy is forming at Princeton University. An organization has been launched seeking to develop authors to revitalize Catholic literature. Once again, after several false starts, another attempt is being made to create a national Catholic magazine: The Lamp. The initiatives on the musical front are too numerous to describe here. Finally, just in my immediate neighborhood, three major new “conservative“ Catholic (using that term somewhat loosely) schools are in the process of formation (joining one already existing independent Catholic classical school). This is in the diocese of Bridgeport, Connecticut, where just 16 years ago no school of this kind existed at all.

Now I might very well have critical comments on aspects of these initiatives. As always among Conservative Catholics, moreover, not all these groups are aligned. To some extent, the temptation remains of substituting apostolic activity for spiritual development – or of utilizing it to avoid facing reality. Yet the continued vitality of the “orthodox” wing of Catholicism – largely supported by the laity on a voluntary basis – cannot be denied. And we are also happy to note that some – certainly not all – of these initiatives are open to cooperation with Traditionalists. The self-understanding of Conservative Catholicism as the “Uniate” alternative to Traditionalism is in a steadily eroding.

- For a discussion of the term “Catholic Conservatism” – as opposed to the clerical establishment on the one hand and Traditionalism on the other – see Catholic Traditionalism in the United States, Notes for a History; Part 2

16

May

Integralism

Posted by Stuart Chessman

Integralism: a Manual of Political Philososphy

by Thomas Crean and Alan Fimister

(Eurospan, Editiones Scholasticae, Neunkirchen-Seelscheid, 2020)

Politics and the Sacred – an eternal theme. A whole series of thinkers on the right have denounced the “original sin” of the modern democratic state, whether liberal on authoritarian: the severance of the political from the sacred order. Among the Catholics, we could mention, for instance, the fundamental editorial positions of Triumph magazine from its very first issue in 1966. Thomas Molnar – who early on had also been associated with Triumph – wrote often and eloquently on this topic, e.g., Twin Powers: Politics and the Sacred(1988), Moi, Symmaque (1999). This line of thought contrasts, however, with the current position of the Catholic Church, which had embraced the “sound laicity” (Ratzinger). of the modern Western states. Indeed, the Church establishment has often gone further and claimed the modem political world to be the inevitable product of Christianity. Thus, the non-Christian polity of today paradoxically receives divine sanction – a weird second-coming of Christendom!

Challenging the latter views is integralism, a movement, mainly among academics, which in essence aims to recover the principles and positions of Catholic political philosophy as it existed prior to the last Council or even prior to 1789. Integralism (2020) by Thomas Crean and Alan Fimister is a “manual of political philosophy” summarizing the positions of the movement. It is a remarkable survey of all aspects of political philosophy: the philosophical foundations, the forms of political organization, the relation of state and Church, economics, warfare etc. The authors distinguish the political relationships in Christendom from those that exist outside of it (such as in the world of today). As sources the authors cite primarily Neo-scholastic philosophy and theology, the ancient philosophers, papal declarations and decrees from many eras and thinkers ranging from Thomas Aquinas to Robert Bellarmine and Alasdair MacIntyre.

Integralism summarizes for us the many political positions taken by the Church both in the age of Christendom and later – including those that the Church today would like to forget – such as those on religious toleration, just war, slavery, the death penalty, etc. Crean’s and Fimister’s “manual” is succinct and clear. To be sure, I was startled now and then by certain expressions and turns of phrase. For example, “[T]he entity (the C of E – SC) created by Henry VIII and his natural daughter is notoriously founded upon attempted divorce.” On the whole I thought the authors did a good job of presenting this vast subject matter. I might of course question the basis for one or other of their claims,- such as that English Common Law parallels the Roman Jus Gentium.

My fundamental criticism though, regards what I perceive to be a lack of historical context inherent in the integralists’ philosophical/theological/legalistic approach. For politics, after all, deals with the real – as it is encountered in the present day but also in history. Yes, political action should be informed by theological and philosophical principles – but it cannot simply be deduced from them.

This historical gap can be illustrated the authors’ discussion of the scope of papal authority in temporal affairs. The authors seem to regard as exemplary the period of the papacy that, historically speaking, existed in “Christendom” between 1050 and 1300 – and then really only fully in a small subset of that era: from around 1200 to 1230. The authors rely on Boniface VIII’s Unam Sanctam as a source – yet even when that was written (1302) it no longer accurately described reality. At the same time, the authors describe a constitution of the Church as it was perfected after 1870. But this structure in large part only became possible in the regime of post-Christendom liberalism. I was also unconvinced when the authors seek to establish the continuity of their description of papal authority with the practices of the Church prior to 1050 or, even more so, with the positions set forth in Vatican II documents and encyclicals and statements of recent popes.

We might add that the “rulers” and “temporal authority” discussed in this book have also changed radically over the ages: from Roman emperors to anointed medieval rulers to the modern state to the current postmodern despotism of “civil society.” A complete Catholic manual of political philosophy would have to devote much more space to these specific facts. The authors are of course aware of the differences among these forms of polity. I was intrigued by their very interesting discussion of “shadow politics” – where the official possessors of power are not those who exercise it in reality (such as a plutocracy). Or by their use of the Platonic term “theatrocracy” – “where poets corrupted the judgments of citizens by vicious music” to describe “a state of affairs where men are ruled by those who possess the means of mass communication.”

Indeed, it is this aspect of integralism – the authors’ unambiguous assertion of papal rights in temporal affairs – that has stirred up the greatest resistance. To be fair, at least as presented in this “manual,” the topic of the pope’s temporal authority is just one of many. Yet it does illustrate well the authors’ relative lack of concern with either historical reality or the actual expertise of the papacy in temporal affairs. For even in the 13th century – the golden age of papal rule – the political decisions of the popes were highly controversial and often laid the foundations for subsequent conflicts. The same is true of the political decisions taken by the post-1870 popes – from the ralliement to the French republic to the condemnation of Action Francaise to the concordat with the Third Reich.

And what of the Church of today? How could anyone seriously consider entrusting political authority to an institution like the Vatican? From the pontificate of Paul VI to the present day we have witnessed an unending series of financial, political and sexual scandals. Works like Gone with the Wind in the Vatican ( Via col Vento in Vaticano(1999)) reveal the Vatican to be an abyss of corruption, dishonesty, incompetence, careerism and exploitation of subordinates. And what are we to think about the ruling style of the current pontiff: despotic, arbitrary, having profound disregard for all laws and customs – yet at the same time totally subservient to the forces of the secular “power elite.” It seems incredible to appear to argue that this man and this institution in its current form are capable of assuming any role in temporal affairs. For let us remember that in the great era of medieval papal power the Church and the curia offered men real secular advantages over the feudal powers of that day: a better judicial system, a better organized and more efficient bureaucracy, the beginnings of an informed patronage of the arts.

So I applaud the initiative of the integralists – even if I cannot endorse all aspects of their program. The disconnect, created by modern secularism, between politics and the sacred is something that for the sake of human society must be healed. How that will happen, though, is something I do not know. One thing seems clear – the foundation of such a restored political order presupposes the conversion to Christianity of the people who make it up. And achieving that conversion should be the focus of all our efforts.

16

May

For the Vigil of the Pentecost, on Saturday May 22, Sts. Cyril and Methodius in Bridgeport, CT will offer a high Mass at 9 am, including the Prophecies, blessing of the font and Mass.

St. Patrick Oratory in Waterbury, Ct will follow the same schedule: at 9 am, the Prophecies, blessing of the font and a high Mass.

11

May

Contact us

Register

- Registration is easy: send an e-mail to contact@sthughofcluny.org.

In addition to your e-mail address, you

may include your mailing addresss

and telephone number. We will add you

to the Society's contact list.

Search

Categories

- 2011 Conference on Summorum Pontifcum (5)

- Book Reviews (98)

- Catholic Traditionalism in the United States (24)

- Chartres pIlgrimage (17)

- Essays (178)

- Events (681)

- Film Review (7)

- Making all Things New (44)

- Martin Mosebach (35)

- Masses (1,357)

- Mr. Screwtape (46)

- Obituaries (18)

- On the Trail of the Holy Roman Empire (23)

- Photos (349)

- Pilgrimage Summorum Pontificum 2021 (7)

- Pilgrimage Summorum Pontificum 2022 (6)

- Pilgrimage Summorum Pontificum 2023 (4)

- Sermons (79)

- St. Mary's Holy Week 2019 (10)

- St. Mary's Holy Week 2022 (7)

- St. Mary's Holy Week 2023 (7)

- St. Mary's Holy Week 2024 (6)

- Summorum Pontificum Pilgrimage 2024 (2)

- Summorum Pontificum Pilgrimage 2025 (7)

- The Churches of New York (199)

- Traditionis Custodes (49)

- Uncategorized (1,387)

- Website Highlights (15)

Churches of New York

Holy Roman Empire

Website Highlights

Archives

[powr-hit-counter label="2775648"]