THe Bridgeport diocese now has an “Apologetics Director.”

Brennan, Rose, “Suan Sonna named new Apologetics Director,” 3 Fairfield County Catholic(July/August 2025).

In his new position, Mr. Sonna proposes to invite speakers, to organize retreats, “conversations,” parish “Apologetic Sundays,” “testimony nights,” etc.

“Apologetics Begins,” bridgeportdiocese.org (August 6, 2025)

In Brennan’s article, supra, we learn that :

“(Sonna’s) favorite topics to speak on include sacred Scripture, moral theology and the papacy. Notably, his article “Lessons from St Peter’s Papacy” will appear in the upcoming book Faith in Crisis: Critical Dialogues in Catholic Traditionalism, Magisterial Authority and Reform.”

But what kind of book is Faith in Crisis (Andrew Likoudis, ed., En Route Books and Media, St Louis MO)?

Judging from the extensive blurbs in the advance notice, it will be first and foremost an anti-traditionalist polemic. Then, it will defend the papacy as it was exercised under Pope Francis. The overall objective will undoubtedly be to vindicate the clerical establishment.

The editor is Andrew Likoudis:

Andrew Likoudis is a Catholic scholar and entrepreneur with degrees in Communication from Towson University and Business Administration from the Community College of Baltimore County. He has served as a fellow at Johns Hopkins University and at Goldman Sachs’ 10,000 Small Businesses initiative. His professional experience includes a role as a business development administrative assistant at theCathedral of Mary Our Queen. Additionally, he has nearly a decade of experience providing hospitality hosting with Airbnb.

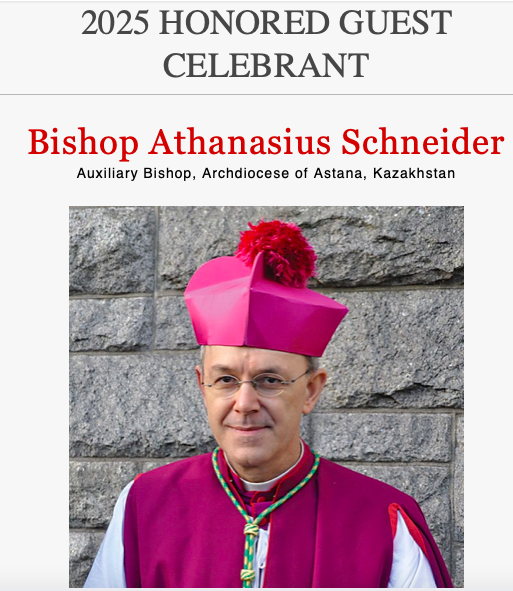

Some well-known contributors are drawn from the blogging/podcast world (Mike Lewis, of course); most of the others (like Mr. Sunna) are in the employ of the Roman Catholic Church. But a couple stand out. Rocco Buttiglione, who writes the foreword, is a “conservative” – centrist Italian academic and politician. The last I heard of him, Buttiglione was aggressively defending Pope Francis and specifically Amoris Laetitia. The only real surprise is Cardinal Sarah. Will his contribution discuss his involvement with the traditionalist Chartres pilgrimage? Or his experiences dealing with both a Pope and a Pope Emeritus at the time of the “Amazonian” synod?

The entire project of this book is very establishment (or would-be establishment): confrontational anti-traditionalism, blind ultramontane devotion to the papacy combined with very attenuated “conservative Catholic” notions and charismatic nuances. Now Faith in Crisis has not yet been published. I wonder: are the publisher and perhaps certain contributors waiting to see what direction Pope Leo takes before launching a new assault in the intra-Catholic culture wars? Moreover, the ideological alliance of the contributors in this book is inherently unstable. Consider that En Route Books and Media (the publisher of Faith in Crisis) still prominently features in its catalogue works by Detroit seminary professor Eduardo Echeverria – who was recently summarily sacked by the arch-Bergoglian Archbishop of Detroit.

It seems to me that the present task of Catholic apologetics is to facilitate the recovery of a faith that has been eclipsed – not just among the laity, but also among the clergy and church bureaucracy. Defending the papacy and the institutional Church no longer primarily means, as it did in the 19th century, repelling attacks by outside enemies. Rather, under Francis, these controversial themes primarily served a role in the intra-Catholic cultural wars waged by a once unthinkable alliance of an ecclesiastical bureaucratic establishment and the progressive ( “modernist”) forces. These conflicts have only accelerated the decline of the faith. A valid apologetics would not focus on Church politics and internal enemies but on rekindling the faith. But is that possible? Do we dare admit that we cannot transmit our beliefs when our own faith has become nebulous and uncertain? You cannot give to others what you do not have yourself!