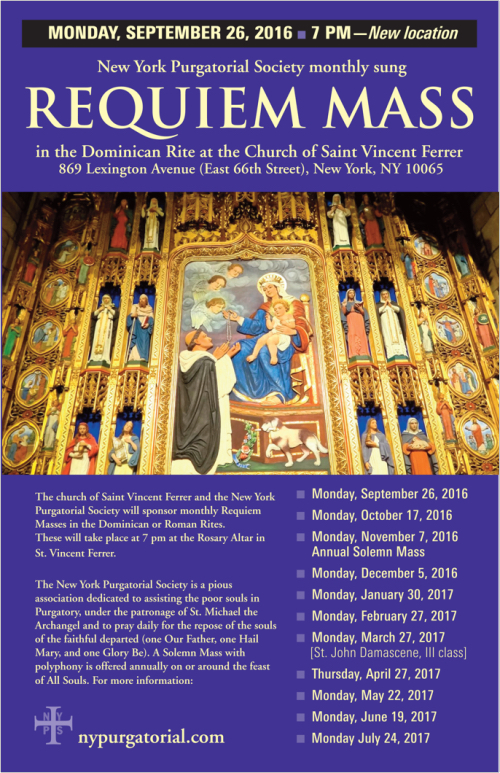

Tonight the New York Purgatorial Society will offer its monthly Requiem Mass in the Dominican Rite at 7 pm. Please note the new location: St. Vincent Ferrer Church, 869 Lexington Ave., New York.

26

Sep

26

Sep

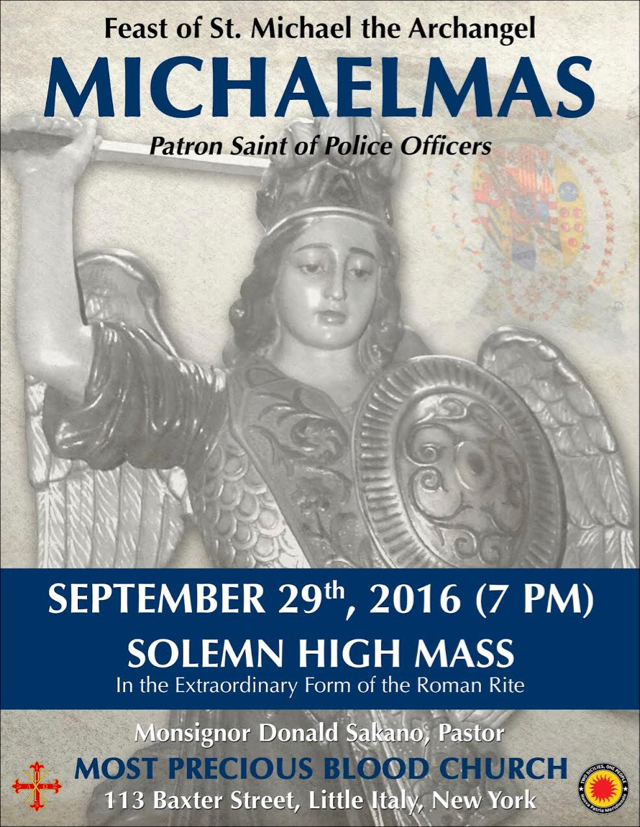

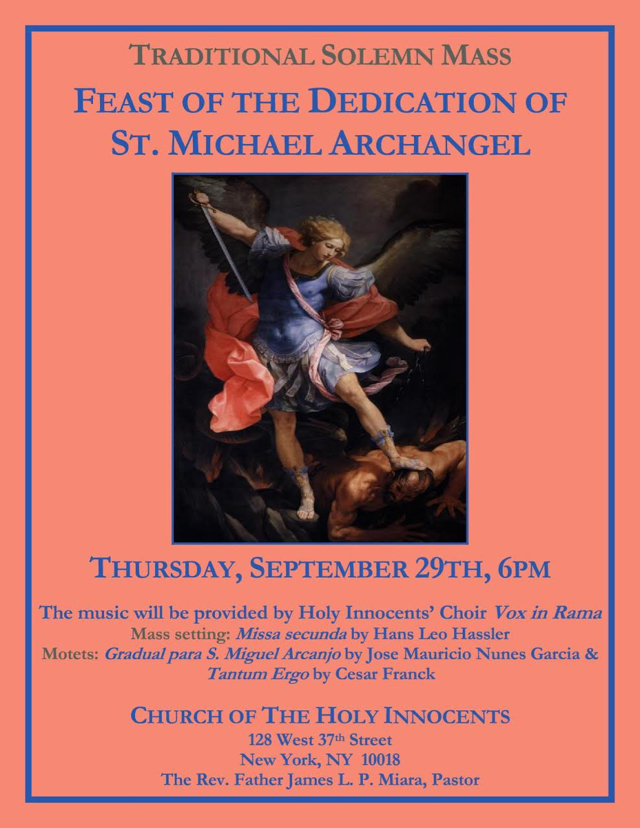

On Thursday, September 29th, in honor of the Feast of St. Michael the Archangel, there will be celebrated a Solemn High Traditional Latin Mass at 7:00 p.m. at the historic Church of the Most Precious Blood located in New York City’s Little Italy. The intention of the Mass will be for the spiritual and physical well being of all police and law enforcement officers. This Mass and the Mass at Holy Innocents at 6:00 p.m. will make for two Solemn Traditional Latin Masses being celebrated almost simultaneously a few short miles from each other in Manhattan, and such an occurrence, just a few short years ago, would have seemed impossible.

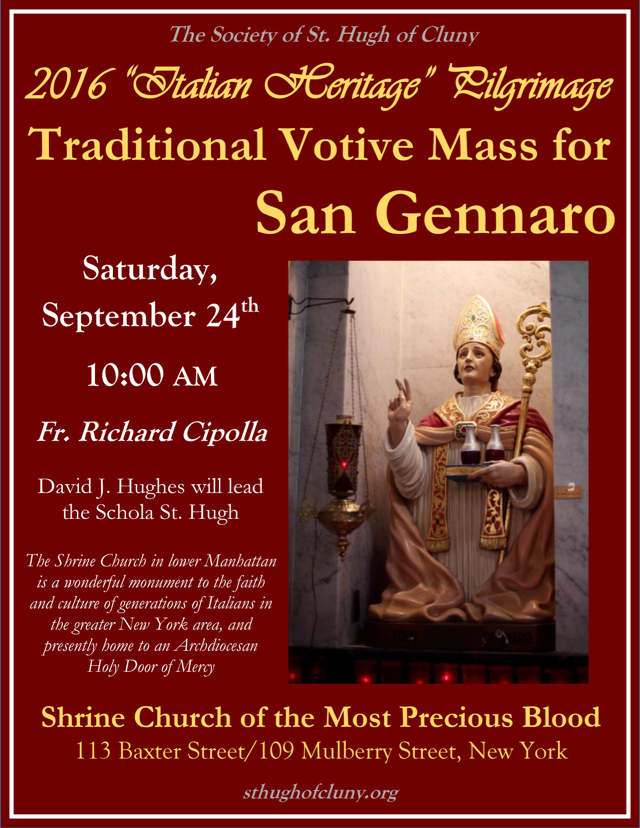

(Above) San Gennaro – or St. Januarius.

Solemn High Mass yesterday at the church of the Most Precious Blood – amid the noise and crowds of the San Gennaro Festival in New York’s Little Italy.

(Above) The first Solemn Traditional Mass in ages in this church – but the next is already scheduled for the 29th of September! It was a privilege for this Society to sponsor this mass in such a repository of Catholic tradition. The music included, among other works, Mozart’s Missa brevis in F (K. 192). Our thanks to Msgr Donald Sakano, Pastor of Old St Patrick’s and of Most Precious Blood, for the invitation to sponsor this mass during the San Gennaro festival!

(Above and Below) Occupying much of the rear of the nave is a huge Neapolitan Christmas creche. The church of the Most Precious Blood is a treasury of Catholic and Italian devotions. For more on this church see HERE

(Above) The Sermon – amid the forest of statues. For Fr. Cipolla’s sermon see HERE.

(Above) Good participation for such a small church – including some who ventured in from the nearby festa on Mulberry Street.

24

Sep

Sermon for the Votive Mass of San Gennaro

by Father Richard Gennaro Cipolla

Saturday, September 24, 2016

Shrine Church of the Most Precious Blood, New York, NY

And behold, a woman of the city, who was a sinner, when she learned that he was sitting at table in the Pharisee’s house, brought an alabaster flask of ointment, and standing behind him at his feet, weeping, she began to wet his feet with her tears, and wiped them with the hair of her head, and kissed his feet, and anointed them with the ointment. Luke 7:37

What a wonderful thing to come to this church to celebrate this Solemn Votive Mass of San Gennaro! This church is redolent with a century’s worth of religious and cultural memories centered around the feast of San Gennaro. We know little about the saint’s life, but the most important information comes from St. Paulinus of Nola, who said: he was bishop as well as martyr, an illustrious member of the Neapolitan church.”. San Gennaro was martyred in the Diocletian persecutions, together with Festus, his deacon, and others from the Naples area. But what everyone knows about him is that his blood, put into 2 vials by a pious woman after his beheading, liquefies on his feast day and two other times in the year. So we can imagine what went on in Naples this past Monday, as the crowds gathered at the Cathedral to witness the liquefication of San Gennaro’s blood. The Church blesses this celebration but has no official statement on this phenomenon.

But why are we celebrating this Mass and this feast so far from the city of Naples? Because of the Italian immigrants from the Naples area who came to New York City during the waves of immigration from the late nineteenth century to the first part of the twentieth century. They came here to escape the poverty in Southern Italy. What they found here often was not that much better, as Mother Cabrini found out and then ministered to these people in such a wonderful way. But they also brought their religion with them, as well as the food from the Naples area. An integral part of their Catholicism was the feasts and fasts, especially the feasts that are an important part of being Catholic and the manifestation of the Catholic faith.

I remember growing up in Providence, Rhode Island, in what was an Italian ghetto. I did not know I lived in a ghetto. All I knew was that everyone around me spoke Italian, or rather some southern dialect, and everyone ate endless variations of pasta and things that Americans would never eat like squid. I remember the processions in the streets with the statue of the saint being carried by men in special and colorful dress, the marching band, many altar boys, priests in their cassocks, surplices and birettas, the pinning of the dollar bills on the statue as offerings for the poor, the smell of the food in the carts in the street waiting to be devoured, the old nonnas dressed in black with their fans, the eyes of those who came from Italy moist with remembrance of the towns and villages that they came from, the children whose minds were being filled with memories of sight and smell and sound. I was an onlooker to all of this, not a participant, for my family were Protestant. Both of my grandfathers, who grew up as Catholics in Italy, became Protestant at some time in their lives, and like all Italian Protestants, were violently anti-Catholic. My family always made fun of these festas and of the procession. They declared it as an example of idolatry and pagan superstition, and thanked God that they had been delivered from that debased form of Christianity called Catholicism. But try as they could, they could not wash out that cultural Catholicism from their lives, for the food they ate, the language they spoke, the customs they observed were all derived from the Catholic faith in which they had all grown up.

But the opposition to public feasts did not come only from a handful of Italian Protestants. It came from the Protestant soul of this country, where religion was understood as a private matter and involved going to church on Sunday and that was it. In this privatization of Christianity, Protestantism paved the way to the secularism with which we are now surrounded. Protestantism demands a strict demarcation between the sacred and the profane, with the result that the profane takes over the world. Neither Jonathan Edwards nor the slick tele-evangelists of our time would have been at home at the wedding feast at Cana nor at the dinners with the tax collectors and publicans nor at the dinner at which the prostitute anointed Jesus’ feet with costly aromatic nard.

But the opposition to street Catholicism came also from the Catholic hierarchy at that time. The Irish hierarchy, especially of New York, certainly were strangers to processions and such things, because of the religious situation in Ireland, which ironically forced them to assimilate the Protestant attitude towards the sacred and the profane. The hierarchy had made their peace with the Protestant soul of this country, and so they were disturbed by these displays of religion outside of the church building, where the sacred and profane were on display for all to see. And especially all of this in its Italian immigrant form, which was not always, shall we say, in the best of taste.

The San Gennaro festival began as a lay initiative in which owners of local cafés organized a small festival in honor of the saint. It grew to something that was an integral part of the life of New York City. And it was always that promiscuous mixture of the sacred and the profane that at once repelled and fascinated those who came down to Little Italy to take part in their own way this singular event. And yet by the time of the 1970s the festival had taken on those dark overtones that Martin Scorsese depicted in his wonderful film, Mean Streets, where organized crime in the form of small time Italian hoods, are not merely involved with the festival but already do not understand its roots and its meaning for the first and second generation immigrants. The irony is that the popularity of the San Gennaro festival undermined that ethnic culture that understood the sacred roots of these traditions and the relationships between family, religion and food.

The destruction of ethnic Catholic culture, whether it be Italian or German or French and even Hispanic culture that is being diluted at a dizzying pace as we speak, is part of why contemporary Catholicism in this country is often a pale imitation of secular culture although with an appreciation for upholding basic moral norms. And this is not merely a cultural problem. This is a spiritual problem.

It means so much to me to celebrate this Mass today at the San Gennaro festival which saint’s name was that of my grandfather and given to me as well. My Italian heritage is a deep part of the person I am. But I fully recognize that the Catholic faith transcends ethnic culture; that’s what Catholic means. We cannot bring back that peculiar integration of family, religion and food that marked ethic cultures of the past. But we must never forget that what bound all these ethnic cultures was the Mass we are celebrating here today. It is the Traditional Roman Mass in Latin that both transcended and bound these cultures into the one Catholic Church. This Mass is the distillation of many cultures for almost two millennia and therefore is the fertile womb even in our secularized world for the re-flowering of Catholic culture. This Mass is the antidote to the decomposition of Catholicism into a porridge fit only for a baby with no taste. Let us ask the intercession of San Gennaro that the bishops and priests of the Church come to understand and love the Mass of Catholic Tradition as the soil in which Catholic culture will re-flower and fill the whole world with that peculiar fragrance that is a mixture of sausage and peppers and the costly ointment with which Mary Magdelene anointed Jesus’ feet.

San Gennaro: prega per noi.

22

Sep

20

Sep

18

Sep

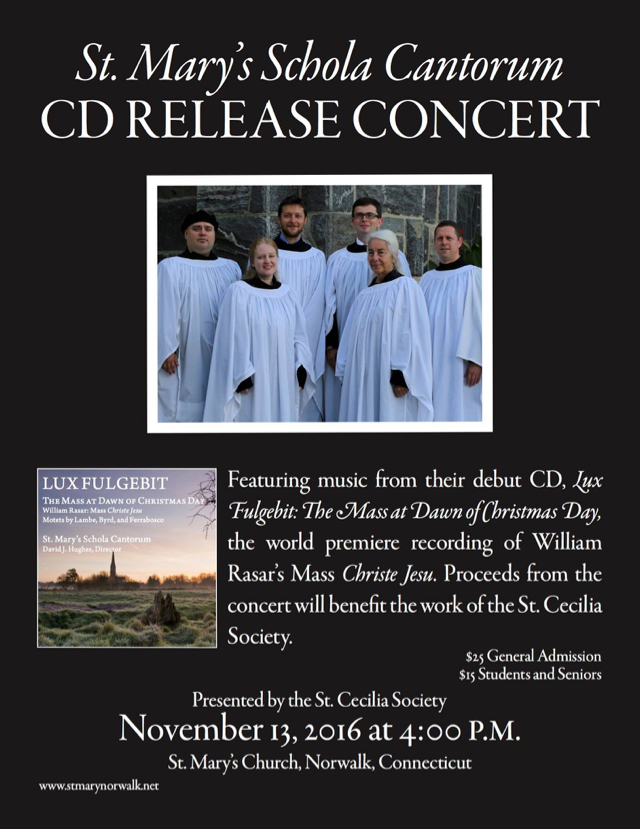

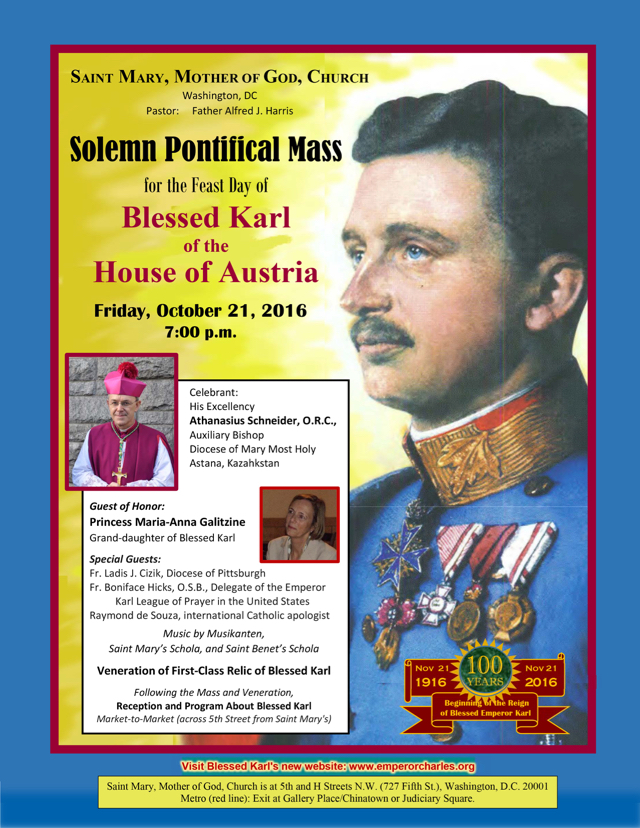

Bishop Athanasius Schneider, auxiliary bishop of Astana, Kazakhstan, will visit numerous churches in the Northeast in October. All masses listed here are traditional masses. (The photo shows Bishop Schneider during a Solemn Pontifical Mass at St. Mary’s Church, Norwalk on January 6, 2013)

18 October 2016, 6:00 PM

Pontifical Low Mass, Dinner & Conference, St. Titus Church

Aliquippa, PA

Wednesday, 19 October 2016, 1:00 PM

Lecture, St. Vincent de Paul Church

Berkeley Springs, WV

Thursday, 20 October 2016, 6:00 PM

Lecture, Cosmos Club

Washington, DC

Friday, 21 October 2016, 7:00 PM (Feast Day of Blessed Karl of Austria)

Solemn Pontifical Mass & Reception, St. Mary Mother of God Church

Washington, DC

Saturday, 22 October 2016, 8:30 AM

Pontifical Low Mass & Morning of Recollection, St. Thomas Apostle Church

Washington, DC

Sunday, 23 October 2016, 10:30 AM

Solemn Pontifical Mass & Conference, Mater Ecclesiae Church

Berlin, NJ

Monday, 24 October 2016, 6:00 PM

Solemn Pontifical Mass, Church of the Holy Innocents

Manhattan, NY

Tuesday, 25 October 2016, 6:00 PM

Pontifical Low Mass & Conference, Church of the Holy Innocents

Manhattan, NY

Thursday, 27 October 2016, 10:00 AM

Solemn Pontifical Mass, St. Peter Church

Steubenville, OH (Evening lecture.)

These Masses and conferences were coordinated by the Emperor Karl League of Prayers with the support and cooperation of the following Traditional Knights of Columbus councils and organizations:

Regina Coeli Council 423, Manhattan, NY

Potomac Council 433, Washington, DC

Woodlawn Council 2161, Aliquippa, PA

Agnus Dei Council 12361, Manhattan, NY

Mater Ecclesiae Council 12833, Berlin, NJ

The Paulus Institute for the Propagation of Sacred Liturgy

The American Society for the Defense of Tradition, Family, and Property (TFP)

PLMC, Inc.

Una Voce Steubenville

15

Sep

On Saturday, September 24th at 10 am, the Society will sponsor a traditional votive mass for San Gennaro at the Shrine Church of the Most Precious Blood in Little Italy, New York, during the famous Festival of San Gennaro. David Hughes will lead the choir and strings in a Mozart program.

Prelude: Sonata da chiesa in B-flat (K. 212) (Mozart)

Missa brevis in F (K. 192) (Mozart)

Gregorian Mass of Several Martyrs: Salus autem

Motet at the Offertory: Justorum animae (Palestrina)

Motet at the Communion: Venite populi (Mozart)

Postlude: Sonata da chiesa in F (K. 244) (Mozart)

13

Sep

Life is Short

Posted by Stuart ChessmanDas Leben ist Kurz

Zwölf Bagatellen

by Martin Mosebach

(Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg, 2016)

In the United States Martin Mosebach, the liturgical essayist, is well known. Martin Mosebach, the novelist and writer, is far less known. After all, it was only two years ago that one of his novels, What Was Before, was translated into English for the first time. Mosebach has now published Life is Short: Twelve Bagatelles, a collection of his shorter and shortest fiction. If it were only translated, it would be for the American reader an ideal concentrated introduction to the style of Martin Mosebach.

Life is Short gathers previously published short works. In general, I would categorize them as “prose poems” rather than short stories. Rather than presenting a narrative or character, the miniatures in Life is Short describe an object, capture a mood or a moment – often in an indirect, indeterminate way. One thinks of such remote antecedents as Arthur Machen’s Ornaments in Jade (1897) or J-K Huysmans’ Drageoir aux Épices (1874). Mosebach’s style, however, if “poetic” in the use of sound and images, is more restrained and precise. And, as in Mosebach’s novels, here and there is satire and even comedy.

As to things, Life is Short offers numerous descriptions of objects as diverse as a bicycle, a pigeon egg or the wreckage of an (apparently) abandoned barber shop. Mosebach endows mere things with new significance, even (in the case of the bicycle) a life of their own. As William Carlos Williams put it:

“So much depends upon a red wheelbarrow….”

But has not this kind of imagery always been a particular excellence of the author? One remembers so well the sacred cow in Das Beben, or the descriptions of a nightingale and later of the cockatoo in Was Davor Geschah.

These “bagatelles” also capture fleeting, uncertain and sometimes deceptive moments of life such as a boy’s exhilarating bicycle ride downhill after a hard day at school or the glimpse of a mysterious stranger sitting in a train compartment by a rider standing on the platform. If life is short, even more brief are the few moments that allow us insight into in it.

Some of the pieces in Life is Short assume the form of a short story. A tale of an artist and her friend discussing the components of a still life unexpectedly turns unsettling, even menacing. A visit to a dying deserted French town climaxing in a mysterious late night conversation leaves the story’s narrator perplexed as to what he as seen or imagined.

Yes, life is short – but art is long. If you want to get to know Mosebach the artist, this is a good place to start. But what of Mosebach the Catholic advocate, the inspiring writer on the liturgy? In the following brief final section of “Vinusse: Eight Wine Labels and a Prologue,” the author does more explicitly present liturgical and theological themes in an anecdote that takes place in his own backyard, near Frankfurt. It’s a tale that also leaves us with a kind of commentary on the meaning of this little book.

The Wine of Sacrifice

The biretta of the monsignor hung from the hat rack in the foyer. Its glowing crimson pompom was the only sign of baroque pleasure in color in the severe scholar’s dwelling. The old theologian regarded not as old-fashioned ballast, but as extraordinarily meaningful, that, as is often the case in the Rheingau, a vineyard was attached to the rectory. In this way a gift, the purity of which he well knew, entered the gothic chalice with which he offered the sacrifice.

The walls of his study were covered up to the ceiling with brown rows of books. The complete edition of Migne’s church fathers, bound in black-waxed linen, was ready at hand. The afternoon sun created small foci of light in the wine glasses that stood before us.

“This wine is the best that wine can become” said the cleric. “Firne-wine. Once upon a time these wines were desired but today nobody understands anything about them. People believe they have gone bad. And indeed they taste totally different. In many of my Rieslings the Firne sets in just after six or eight years, with others only after twelve or fifteen. The wine grows darker and there develops a taste of fine Spanish snuff tobacco: a hint of turpentine, a breath of noble resin pervades the wine like a marriage, made only in the imagination, between wine and incense. Maybe the wine, impatient and desperate at having to wait for its use in the Sacrifice, undertakes itself an attempt at auto-transubstantiation.

He hadn’t joked, but nevertheless smiled.

“Wine, after all, has been meant for sacrifice from the beginning. When wine was offered in the room of the last supper in Jerusalem that was done not out of the inspiration of the moment but in conscious remembrance of the mysterious, almost prehistoric priest-king Melchizedek, who had likewise made an offering of bread and wine. The matter of a sacrifice is not at our disposal. It is very true: visible things are not the final reality, but a kind of writing, by aid of which the invisible appears. An alphabet has letters that cannot be switched. Like all heresies, the idea arose early on that other substances could replace wine. Around 200 A.D. there was a sect in the Near East – the Aquarians – that in the Christian sacrifice used water instead of wine. To his everlasting fame, St. Cyprian of Carthage put the Aquarians’ madness in its place. Although my Firne – wine is only twenty years old, the Firne endows it with an ancient character. Therefore, with it I greet Saint Cyprian and his struggle against godless anti-sensuousness.”

Contact us

Register

- Registration is easy: send an e-mail to contact@sthughofcluny.org.

In addition to your e-mail address, you

may include your mailing addresss

and telephone number. We will add you

to the Society's contact list.

Search

Categories

- 2011 Conference on Summorum Pontifcum (5)

- Book Reviews (98)

- Catholic Traditionalism in the United States (24)

- Chartres pIlgrimage (17)

- Essays (178)

- Events (682)

- Film Review (7)

- Making all Things New (44)

- Martin Mosebach (35)

- Masses (1,358)

- Mr. Screwtape (46)

- Obituaries (18)

- On the Trail of the Holy Roman Empire (23)

- Photos (349)

- Pilgrimage Summorum Pontificum 2021 (7)

- Pilgrimage Summorum Pontificum 2022 (6)

- Pilgrimage Summorum Pontificum 2023 (4)

- Sermons (79)

- St. Mary's Holy Week 2019 (10)

- St. Mary's Holy Week 2022 (7)

- St. Mary's Holy Week 2023 (7)

- St. Mary's Holy Week 2024 (6)

- Summorum Pontificum Pilgrimage 2024 (2)

- Summorum Pontificum Pilgrimage 2025 (7)

- The Churches of New York (199)

- Traditionis Custodes (49)

- Uncategorized (1,388)

- Website Highlights (15)

Churches of New York

Holy Roman Empire

Website Highlights

Archives

[powr-hit-counter label="2775648"]