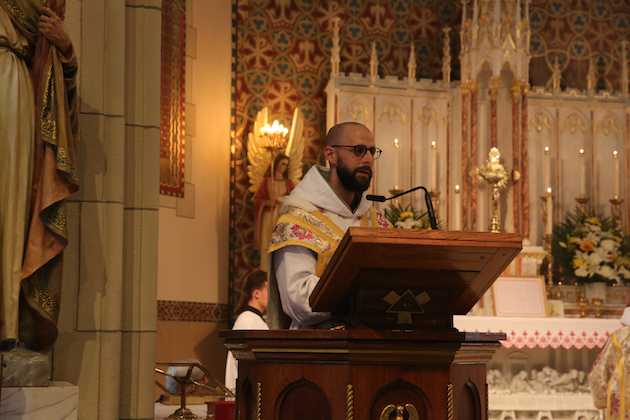

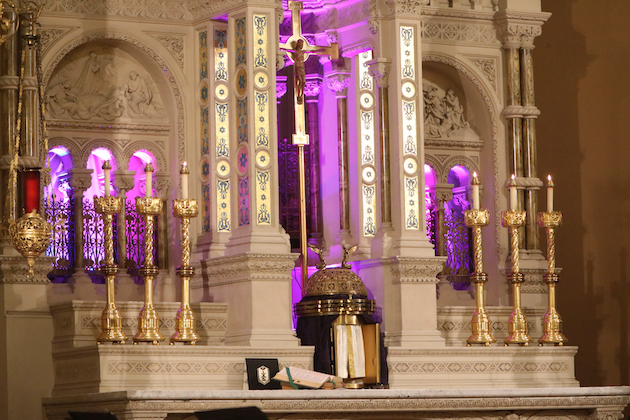

His Emminence Cardinal Raymond Burke celebrated a Solemn Pontifical Mass yestereday evening at the Basilica of St. John the Evangelist in Stamford, CT for the feast of Our Lady of Mount Carmel. In this post we cover the first part of the ceremony, the vesting ceremony. In Part 2, we will cover the Mass itself.

Contine to Part 2