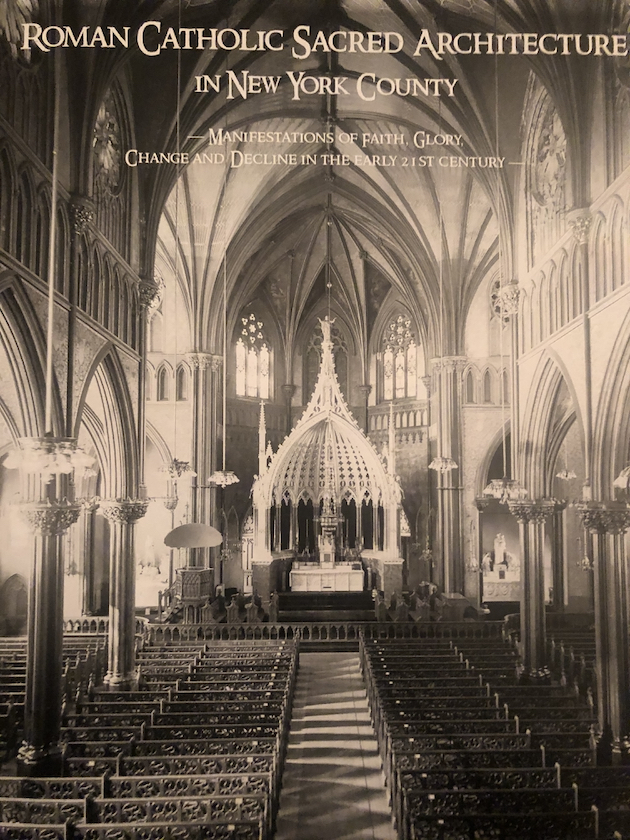

And of the Catholic (and religious?) use of one of the most architecturally significant Catholic church buildings in Manhattan (see our description: “Harlem’s Cathedral”). It is the second magnificent Catholic church in Harlem – after St. Thomas (the latter’s story here) – that has been reduced to profane use by the Archdiocesan planning under Cardinals Egan and Dolan. The speed of the Catholic decline in New York City amazing: All Saints school was closed as recently as 2011, the parish followed in 2015 and the property “relegated to secular use” (deconsecrated) in 2017.

What will be the new owner?

Sean “Diddy” Combs has found a storied new home for his Capital Prep Harlem school.

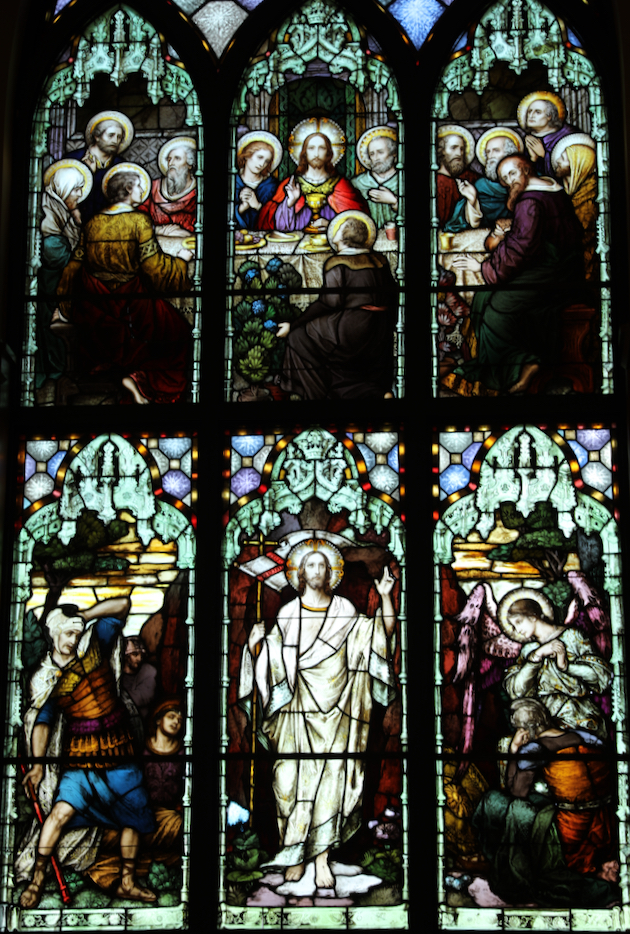

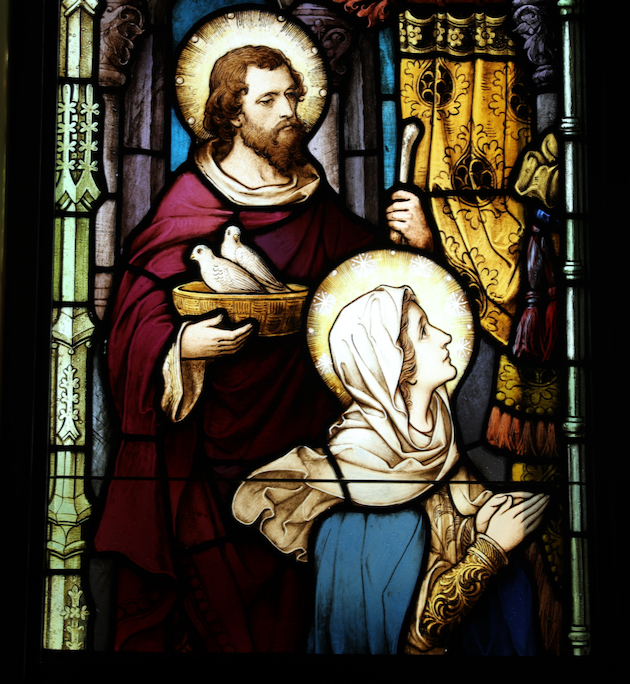

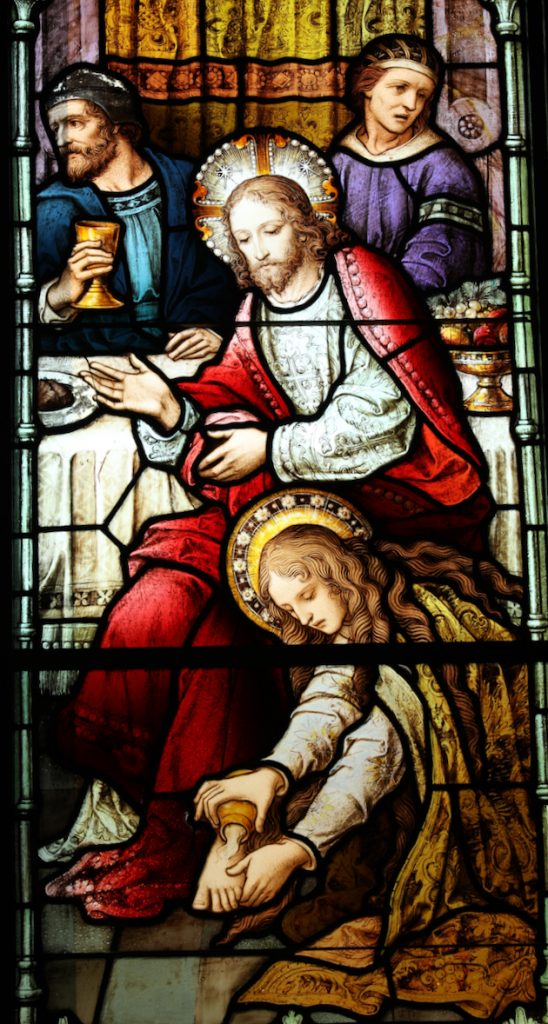

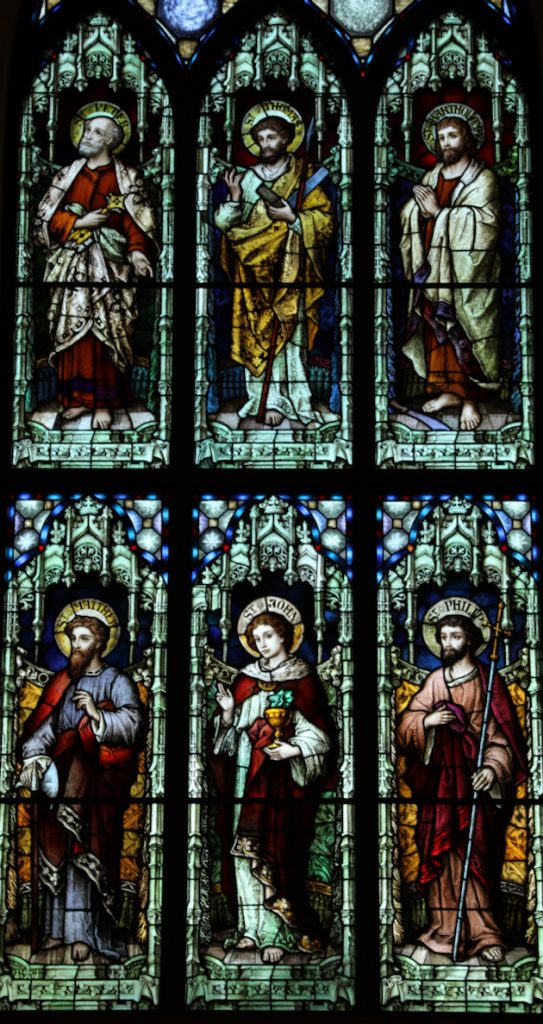

The school is relocating to the former Church of All Saints at East 129th St. and Madison Ave. The site was built in the 1880s and designed by James Renwick Jr., the architect behind St. Patrick’s Cathedral.

The move will allow Diddy’s Harlem academy to increase its capacity from 500 to 700 students in grades six through 12 beginning next school year.

The new campus will house 40 classrooms and offices, science labs, a cafeteria, an outdoor communal courtyard and a “Great Hall” (the former church? – SC) for assemblies and performances.

Mohr, Ian “Sean ‘Diddy’ Combs finds historic home for his Harlem charter school” The New York Post (11/12/2021)

See also: Angermiller, Michele Amabile, “Sean ‘Diddy’ Combs’ Charter School Relocates to Landmark Harlem Church, Increases Student Capacity” Variety (11/11/2021)