(Above: on the facade of St. Michael’s three dates are recorded. 1857 – the foundation of the parish. 1892 – the building of a newer, larger church. 1906 – the relocation of the parish to yet another new building after the expansion of the Pennsylvania railroad “footprint.”)

St. Michael the Archangel

The church of Saint Michael the Archangel offers today a forlorn appearance. The parish has been closed since early 2024. As of today, we do not know what the schedule for reopening, if that ever occurs, will be. Yet, the website of the parish still assures us that the suspension of activity is only temporary:

Church of Saint Michael (stmichaelnyc.org) All references below to the parish bulletin can be found here.

Saint Michael’s twelve years ago was a parish that had obviously seen better days. Yet it remained active and the church building itself seemed in good condition. But even at this time there was talk of a potential sale – the dramatic development of the nearby Hudson Yards had caused real estate values in the immediate neighborhood to skyrocket. Suddenly this out-of-the-way collection of buildings – church, schools, rectory – of a once important Catholic parish had become very valuable indeed.

Fr. George Rutler took over the parish in 2013 and with his usual energy launched a dramatic program of improvements in the interior. The high altar was refurbished. New Statues and shrines were set up. Then in 2019 a new baldachin was erected over a permanent Novus Ordo altar. ( I do have had mixed feelings about that.) Moreover, all kinds of spiritual and social activity returned to St. Michael’s – much of it involving young Catholics. 1) But in 2020 Fr. Rutler stepped down as pastor in the wake of an accusation and, although subsequently the matter was resolved in his favor, did not return. By 2022 a new “temporary administrator” had taken over – a monsignor who had an administrative “day job” with the archdiocese.

(Above) the facade on 34th Street, which may have come partially or totally from the preceding parish church building. (Below) The facade on 33rd street.

The parish bulletins chronicle the subsequent decline of the parish. The July 2nd, 2023, bulletin reported startling – I would think- news. Mrs. Eileen Mulcahy, Vice-chancellor of the archdiocese had addressed all four masses during the prior weekend. She made the following points:

First, the parochial vicar is retiring in a week – she thanked him for his services.

Second, only two masses will henceforward be celebrated on the weekend.

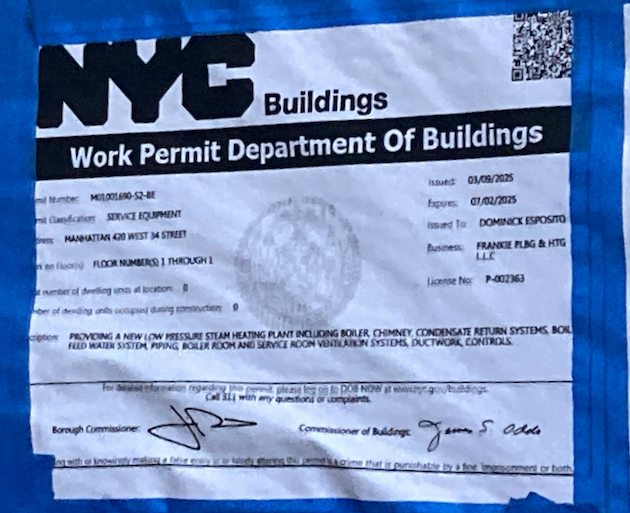

Third, a process to replace the boiler has begun. Because of the noise and potential loss of air quality, the church may have to be closed on weekdays. In any case there will be no further masses at St. Mchael’s on weekdays “until further notice.” (Bulletin July 2, 2023)

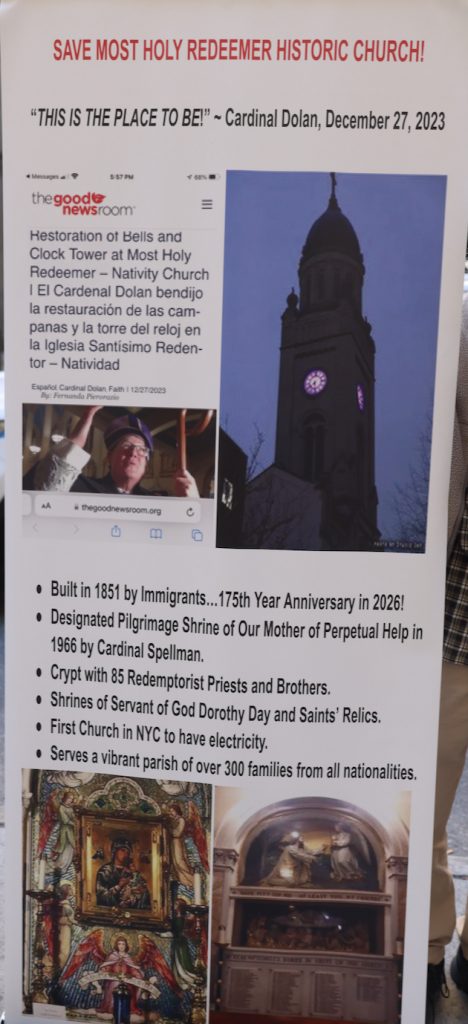

Notice that the bearer of bad tidings was not the archbishop or any other cleric but a lay bureaucrat. Mrs. Mulcahy seems to specialize in this role– she delivered similar news to the parishioners at Most Holy Redeemer church this year.

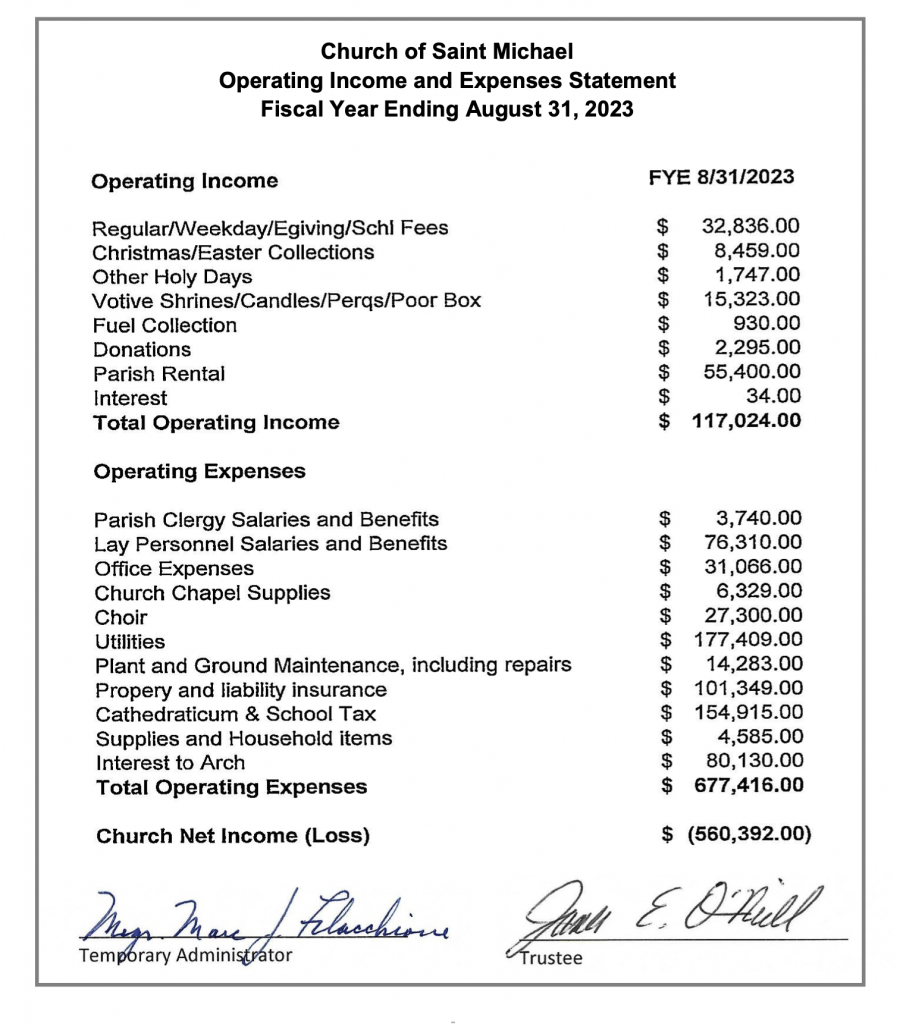

The financial situation of the parish also seems to have gone steadily downhill. Collections at the end as a rule dwindled to around $500 – $700 a week. (e.g., $683 “weekend tithings” – Bulletin, October 15, 2023). The financial statements for fiscal year ending August 31, 2023 showed an annual loss of $560,000. This includes, however, largely notional expenses such as $154,900 for the “cathedraticum” (Archdiocesan assessment) and school tax as well as $80,000 of interest accrued to the archdiocese. It does seem strange that a parish would be charged archdiocesan assessments and school taxes higher than its total income – I do not know how these charges are calculated. Nor do I immediately understand how interest payable to the archdiocese increased in fiscal year 2023 to $80,130 from $1,600 in fiscal year 2022. (Bulletin, January 14, 2024; 2022 financials published in Bulletin, November 6, 2022.)

Finally, Mrs. Eileen Mulcahy announced that as of January 15th, 2024, Saint Michael’s would be closed for renovations until further notice. It was expected that these renovations (including the above-mentioned boiler)would last for at least three months:

Cardinal Dolan asked vice chancellor Mulcahy to assure parishioners that there was no plan to close St. Michael’s permanently. In fact, the new boiler and future renovation plans are part of making the church including its uniquely large assembly spaces, better able to serve the needs of the lower midtown and Hudson Yards work and residential communities for generations to come. (Bulletin, January 14, 2024)

“Uniquely large assembly places” what an odd description of a Catholic sacred space!

The parish bulletin also terminates as of that date. Since January 15th, 2024, the parish has remained closed.

St. MIchael’s church forms the center of a complex of now largely unused Catholic buildimgs. (Above) The entrance to the “world-class” – in size – rectory on 34th street; (below) the facade of the church embedded in a series of institutional buildings on 33rd street.

Based on the above data and the undoubted potential value of the real estate under the parish and its buildings I would view the situation of St. Michael’s as terminal. However, there are countervailing arguments . First, it seems that after a delay of a year to a year and a half since the project was announced, building permits were indeed issued for boiler work. It would seem odd to be investing substantial amounts of money in repairs if the buildings were to be shortly thereafter sold. Second, there have been persistent “rumors“ of a transfer of this parish to one of the (ex-)Ecclesia Dei (“ED”)communities. Indeed, there were reports that in 2021 a deal was imminent until Traditionis Custodes scuttled the project.

If there is substance in these stories, traditionalists finally would obtain the presence of an ED society on Manhattan Island – something that had been previously proposed but blocked by the archdiocese. I think, however, St. MIchael’s might be a mixed blessing. First, I suspect it would be accompanied by shutting down nearby Holy Innocents parish (ten years ago it had been rumored that both St. Michael’s and Holy Innocents parish were targeted for disposition.) Second, I would be concerned that any hand over to an ED community would only be a temporary measure until the archdiocese could arrange a subsequent sale of some or all of the property. Third, there are much more attractive possibilities for a traditional order on the island of Manhattan today – such as Most Holy Redeemer church. Regardless of whatever comes of this talk, it would be shameful to abandon the Catholic presence in this neighborhood as it is being transformed into a new ecomomic center of New York.

1, For our earlier reports on St. Michael the Archangel parish (including descriptions of the interior) see New Baldacchino at St. Michael’s Parish, New York (June 9, 2019); Restoration of the Reredos of St. Michael’s Church, New York ( July 12, 2015); The Churches of New York XXXI: the Wrong Side of the Tracks (January 30 2013).(all The Society of St. Hugh of Cluny)

(Above) Evidence that a permit was issued for work on a boiler in 2024-25).

(Above) The threat to St. MIchael’s – the Hudson Yards development)