7

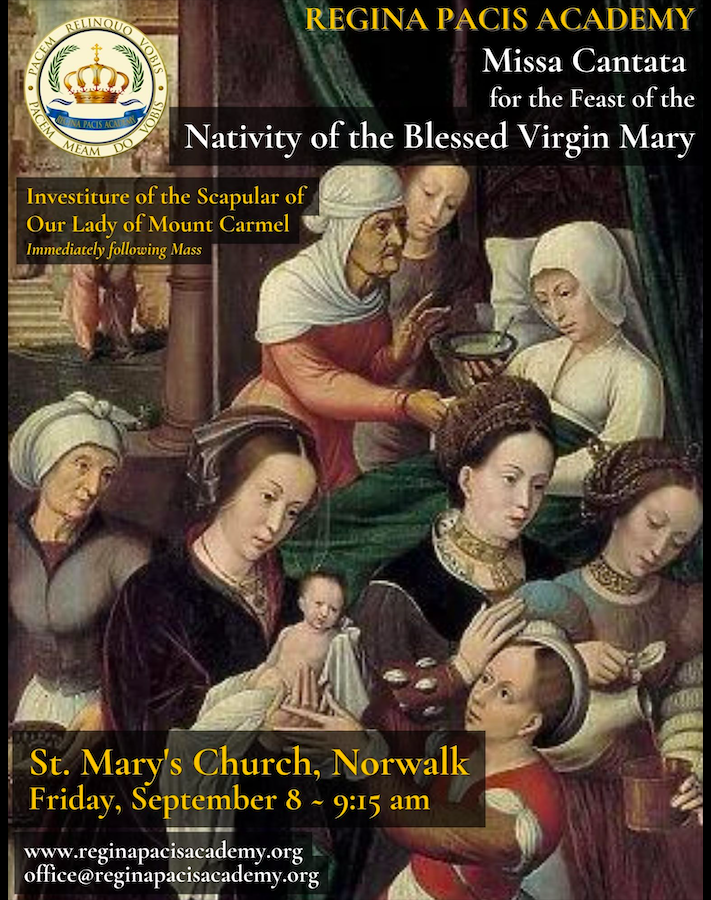

Sep

4

Sep

4

Sep

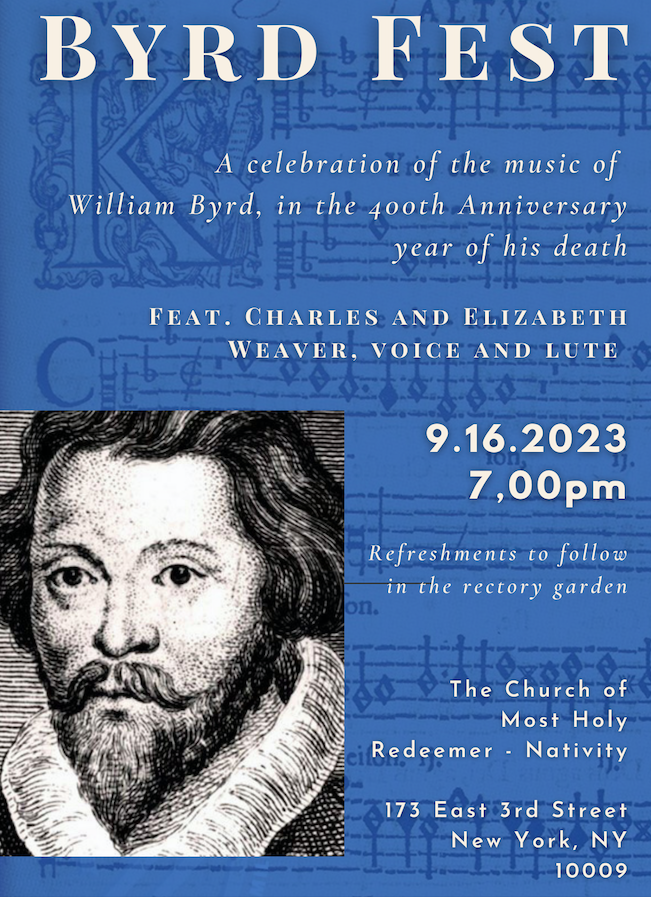

Mark your calendars so you can be sure to come to the Church of Most Holy Redeemer (173 E 3rd St) for “Byrd Fest”–a concert of the great recusant English Renaissance composer William Byrd who died 400 years ago this year. Byrd’s legacy includes more than over 400 pieces of music composed at a time when the Catholic faith was outlawed in his country. His life reminds us that even in times of persecution, great Catholic art is still possible and worthwhile.

Performers include some of the finest singers and lute players on the NYC early music scene – Charles and Elizabeth Weaver (faculty at Juilliard, and faithful Catholics); Terrence Fay, and Grant Herreid.

Free and open to all; reception to follow in the rectory garden.

31

Aug

Infallibility, Integrity and Obedience

The Papacy and the Roman Catholic Church 1848-2023

John M. Rist

James Clarke & Co., Cambridge (U.K.), 2023

Daily we see fresh evidence of the immense stress on the Catholic Church caused by the papacy of Francis. It is a crisis that the Church establishment cannot acknowledge, let alone confront. The distinguished scholar John Rist has made an important contribution to the developing awareness of these issues. HIs Infallibility, Integrity and Obedience frankly addresses the role of the papacy and of the bishops in the last 170 years.

Rist sets forth his arguments in a short historical review of the papacy in the modern era (post- 1846). Infallibility, Integrity and Obedience is always direct at times colorful and often idiosyncratic – Rist never holds back with his opinions and insights on a whole variety of subjects more or less related to his topic. For example, he defends (twice!) the late Cardinal Daniélou from suspicions to which the circumstances of his death might give rise. At times there is sly humor. This book features a Very Select Bibliography. Rist sets before each of the paragraphs of this book several quotations from all kinds of sources. For the chapter on Pope Benedict, we find affixed:

But what about that dreadful Pope?

German Lutheran pastor (female) encountered in Iceland.

Best Pope For 300 years.

John M. Rist

Rist appears to me to have been one of the “conservatives” or “centrists” driven to a traditional position by the radicalism of Francis (Rist calls him “Francis I” on one occasion). Our author converted to Catholicism in 1980 largely motivated by John Paul II’s pro-life advocacy, and obviously still reveres him. Now Rist has had to witness Francis’s systematic undoing of the pro-life legacy of John Paul II. Rist has signed a statement accusing Francis of heresy.

Rist fearlessly points out contradictions and conflicts most Catholics don’t want to hear let alone acknowledge. That the concept of “infallibility” is in practice ambiguous. That the statements of Vatican II on the Church and religious liberty, among other matters, are not exactly reconcilable with those of earlier Councils.(Rist debates several Integralist scholars on this point) That the Vatican cannot talk, as it has done, of reconciling with the Orthodox on the basis of the pre-1054 Councils without calling all its subsequent Councils into question – including the “super Council” Vatican II, I might add. That in any case papal infallibility and supremacy rule out any real union with Orthodox churches.

Above all, Rist understands that the “ultramontane” (our author doesn’t use that term very often) papacy established by Vatican I is and has been a key contributor to the current dysfunction – or should I say collapse – of the Catholic Church. Rist’s thesis is that a papal infallibility and authoritarianism, rather than constituting an impregnable line of defense for the church and tradition, in fact undermined them in the long term. This regime fostered the current notion that Catholic doctrine is a set of rules proposed by authority – which might very well subsequently change these rules. It launched a never-ending quest for clarification and definition of infallibility itself. The post -1870 “creeping infallibility” eventually led to the current situation where every utterance of Pope Francis in whatever form is automatically accorded “magisterial” authority. I particularly liked Rist’s brief but insightful descriptions of the ”collateral damage” of Vatican I – the promotion of habits of servility, conformity and blind obedience throughout the Church. These negative patterns of behavior – this lack of integrity – would bear dreadful fruit.

Rist points out the similarities between the manipulative and authoritarian process leading up to the definitions of Papal infallibility and universal papal jurisdiction in 1870 and the modus operandi employed by Francis today. Indeed, one particular institution – the Jesuit order – played and is playing a key role in the papacies of both Pius IX and Francis. Perhaps Traditionalists might not wholly agree with the author’s sympathies for Döllinger and the more outspoken opponents of infallibility, but they must admit that their fears have become all too terribly real. Most specifically, the episcopate of the Catholic church has indeed been largely reduced to the role of disposable branch managers of the Vatican.

Rist takes a somewhat benevolent, if inconclusive, position regarding Pope John XXIII, Vatican II and Pope Paul VI. One reason seems to be the rehabilitation during and after the Council of a number of theologians previously the recipients of some form of papal censure. Rist does seem to have a fondness for scholars, either in 1870 or in the decades before Vatican II. In my view, however, how can one criticize Pope Francis and his regime without critiquing the substantially identical, and in some cases even more extreme, actions and language of his great hero, Paul VI?

Rist is nevertheless clear that despite reestablishing an equilibrium between the bishops and the Pope being one of its major professed aims, Vatican II in fact reconfirmed the papal hegemony. This was reflected not only in the conciliar texts but in the way Pope Paul managed the Council and its aftermath. Immediate post-Vatican II developments only reinforced the continued decline in episcopal status. The new series of synods were the instruments of further papal manipulation – although not yet as blatant as later under Francis. The creation of national episcopal conferences only served to subject the bishops to local bureaucratic forces.

We have noted Rist’s admiration for John Paul II, as evidenced by the extended exposition of the pope’s writings in this book. Indeed, George Weigel was consulted on the chapter dealing with John Paul II (although Rist says he did not incorporate all his suggestions!). Yet on this chapter’s last pages our author offers a startlingly critical appraisal of John Paul II’s “celebrity autocracy.” He depicts him as blinded by his own self confidence and the desire to focus media attention on himself. His encyclicals were often more his private opinions and were received as such. His limited attempts to restrain the progressive forces – such as his actions regarding the priesthood – often were submerged in a discussion of their infallibility. In such things as his ecumenical initiatives or his appointments, Rist writes, he was influenced by an unduly rosy view of human nature (a surprising flaw for one claimed by his fans to have possessed preeminent political skills). Earlier in this book, Rist has made similar observations about the “optimism” of Paul VI and some of the theologians of the Council. This indicates to me that what we are dealing in all these situations is not an individual character flaw of this or that pope but a widespread ideological conviction that drastically affected the ability of the Catholic leadership to perceive reality.

Finally, we have the papacy of Francis with its “choice against tradition.” The Jesuit order as in 1870 once again plays a dominant role, this time with a radically secular set of objectives. Generally, Francis has avoided a direct assault on tradition– he seeks rather to change the praxis as the method of superseding the rules. But this tactic too may be on the point of changing. So far the servile episcopate, the clergy and laity have acquiesced – or at least have not directly opposed – Francis’s campaign.

I do have my reservations regarding Infallibility, Integrity and Obedience. It focuses on the decisions, statements and writings of popes, scholars and some bishops. The laity, the lower clergy and the non-Catholic world receive more limited and secondary treatment. This is understandable in a book written by an eminent patristic scholar. Yet it is outside the closed circles of the higher clergy and the academy where the actions covered by this book had their greatest impact.

More surprisingly, Rist only briefly mentions liturgical issues. But liturgy – the mass, the other sacraments, the appearance of the churches – is where Vatican II had its most obvious, immediate impact on the faithful. This is where Pope Paul VI exercised most radically papal authority – indeed, the most radical exercise in the entire period covered by this book (matched only by Amoris Laetitia). And this is the battlefield – along with that of “life issues” – where Francis is waging a war to eliminate his opponents.

Developments within the Catholic Church naturally always interact with the general “course of human events” – secular history. To be sure, Rist does now and then consider such influences – such as his description of the weak political position, both in and outside of the Church, of the anti-infallibilists in 1870. Yet more could be said on this interrelationship. De Maistre’s’ thought, for example, illustrates some of the secular political roots of Papal supremacy. The anti-infallibilists in turn were closely associated with the rise of political and economic liberalism, nationalism and the scholarship practiced at German universities (Rist takes a somewhat dim view of the latter phenomenon, then and now). Vatican II itself is inconceivable without the establishment after 1945 of the American world order and the “permissive society.”

In conclusion, Rist offers some “modest conclusions, and less modest suggestions.”

“a model must be constructed whereby the pope is clearly recognizable as the focus of doctrinal unity, but which will simultaneously provide a structure for his activities such as can inhibit the kind of abuse of office which – combined with and encouraging the passivity of too many Catholics – has threatened the Church since papal infallibility was defined at Vatican I and has now seriously infected it.” ( p. 210).

Rist then makes a number of concrete suggestions to achieve this goal:

- Return the appointment of bishops to local control, subject the pope’s veto (for which he must give reasons);

- The election of the pope should be returned in part to a revised group of Roman clergy;

- Misuse of infallibility should be strictly curtailed – ”it should be understood primarily as indicating that the church and the pope should cling to basic Catholic dogma”;

- A hierarchy of “non-dogmatic truths” should be recognized;

- “The church can no longer tolerate either pointless persistence…or the consistently overweening pretensions of a number of uncontrolled religious formations especially the Jesuits and those women’s’ orders roughly grouped under the LCWR…. ;

- No revived “Gallicanism” should be tolerated in national hierarchies, especially in Germany, “where the claim to pursue a local synodal path is reinforced by the belief developed over the last 200 years that they and they alone are the Church’s intellectual elite.” (pp. 211-14)

I doubt all traditionalists would agree with all these recommendations, or that they could be realized in practice. For that matter, all traditionalists would hardly agree with all of the author’s historical conclusions. Yet isn’t this beside the point? I – and I suspect John Rist too – wouldn’t expect every reader to endorse everything that is written in Infallibility, Integrity and Obedience. John Rist has frankly and honestly pointed out a glaring wound in the Church – one that is leading it to extinction in the West. He has the courage to suggest specific actions to help reverse the situation. Such candor is a rare quality in the Catholic Church today. I would recommend this book to everyone who would like to read a challenging, invigorating account of a major aspect of the crisis that is impeding the effective proclamation of the Gospel today.

30

Aug

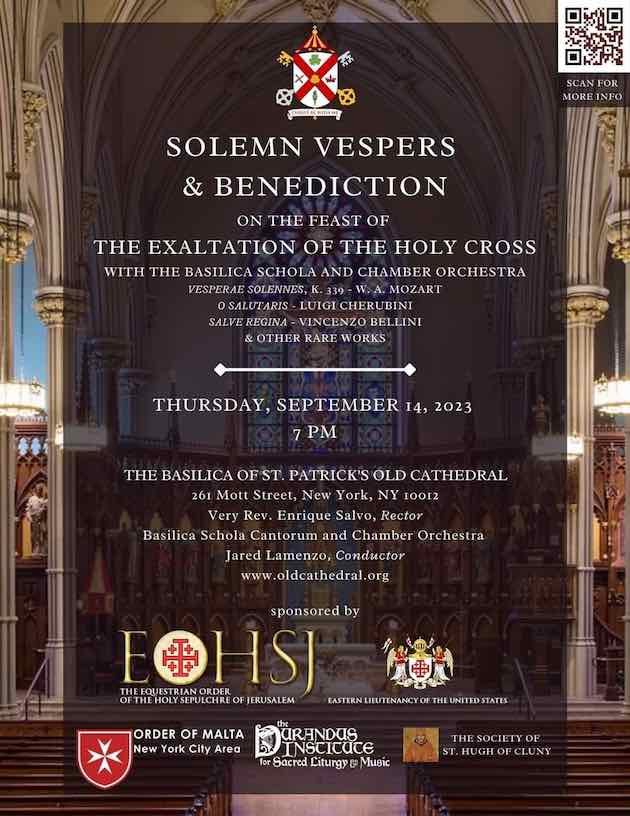

The Durandus Institute for Sacred Liturgy and Music has arranged for the celebration of Solemn Vespers and Benediction at the Basilica of St Patrick’s Old Cathedral in New York City on September 14th, for the Exaltation of the Holy Cross. The Society of St. Hugh of Cluny is a co-sponsor.

A chamber orchestra will assist with some of the greatest choral works ever written for the Divine Office, the centerpiece being Mozart’s Vesperae Solemnes de Confessore, K. 339, to be supplemented with:

Concerto No. 1 in D Major – W. A. Mozart after Johann Christian Bach

Domine ad adjuvandum – Baldassare Galuppi

O Salutaris – Luigi Cherubini

Salve Regina – Vincenzo Bellini

The celebrating priest will be assisted by six other clerics as cantors in copes. Following Vespers will be a short sermon, then Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament. Visitors will also be able to enjoy the celebrations for the feast of San Gennaro, a week-long festival in New York City’s Little Italy district, which begins on this same day.

…for the Feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross, September 14, at 7:00 PM.

(The Society of St Hugh of Cluny is a co-sponsor)

There will be a fundraising party in Jersey City to help finance the choir Cantantes in Cordibus, which sings every Sunday at the Latin Mass at Our Lady of Sorrows in Jersey City.

30

Aug

25

Aug

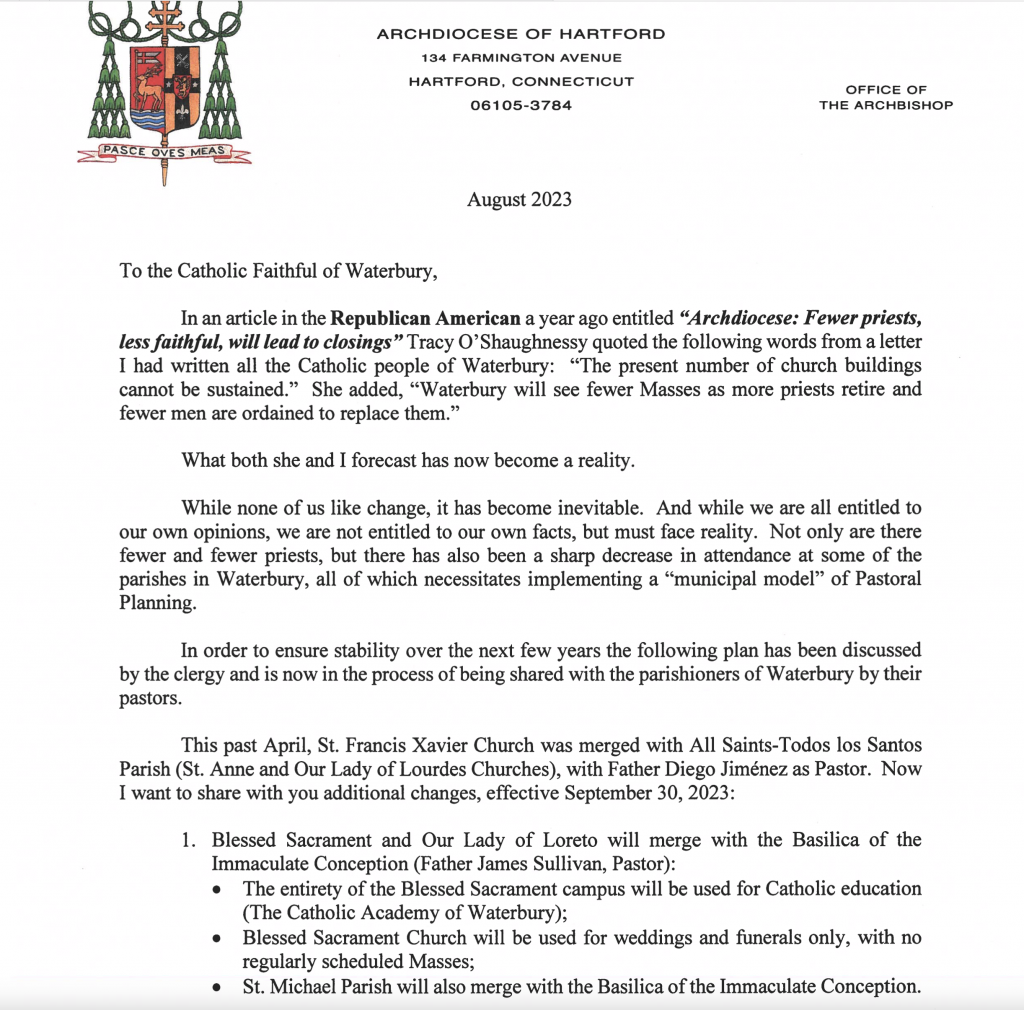

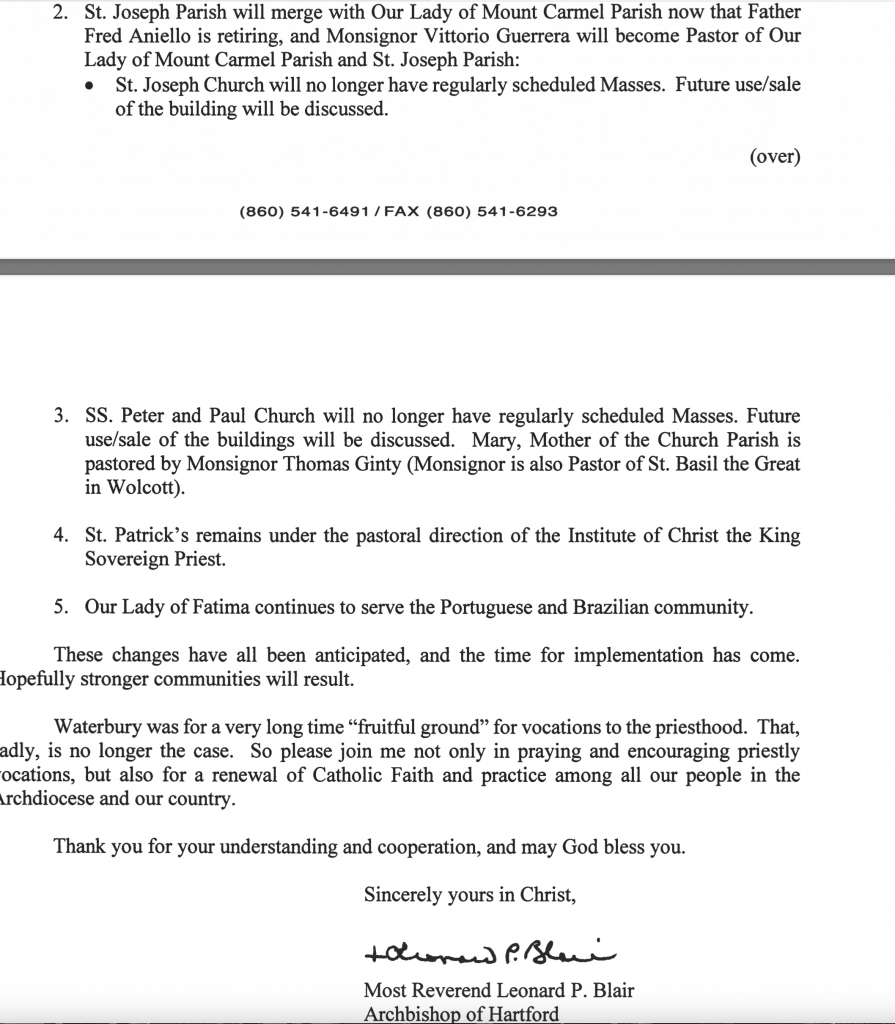

Now It’s Waterbury’s Turn

Posted by Stuart Chessman24

Aug

Contact us

Register

- Registration is easy: send an e-mail to contact@sthughofcluny.org.

In addition to your e-mail address, you

may include your mailing addresss

and telephone number. We will add you

to the Society's contact list.

Search

Categories

- 2011 Conference on Summorum Pontifcum (5)

- Book Reviews (99)

- Catholic Traditionalism in the United States (27)

- Chartres pIlgrimage (17)

- Essays (179)

- Events (686)

- Film Review (7)

- Making all Things New (44)

- Martin Mosebach (35)

- Masses (1,363)

- Mr. Screwtape (46)

- Obituaries (19)

- On the Trail of the Holy Roman Empire (24)

- Photos (350)

- Pilgrimage Summorum Pontificum 2021 (7)

- Pilgrimage Summorum Pontificum 2022 (6)

- Pilgrimage Summorum Pontificum 2023 (4)

- Sermons (79)

- St. Mary's Holy Week 2019 (10)

- St. Mary's Holy Week 2022 (7)

- St. Mary's Holy Week 2023 (7)

- St. Mary's Holy Week 2024 (6)

- Summorum Pontificum Pilgrimage 2024 (2)

- Summorum Pontificum Pilgrimage 2025 (7)

- The Churches of New York (200)

- Traditionis Custodes (52)

- Uncategorized (1,393)

- Website Highlights (15)

Churches of New York

Holy Roman Empire

Website Highlights

Archives

[powr-hit-counter label="2775648"]