13

May

12

May

Cardinal Kasper now explains to the super-neocon Kath.net that he didn’t say some of the things he was reliably reported to have said regarding radical feminist theologians. This “clarification” comes one week after the “offending” statements – which doesn’t exactly inspire confidence. So the Kath.net post states that “the question from the audience concerned a nun (Johnson), who teaches as a theologian at Fordham University,and who Kasper has known for along time – he knows, however, little about her theology.” “So I (says Kasper) made a couple of observations regarding the necessity of dialog for the clarification of the issues, but did not address her theology and even less so the discussions with the union with (sic) major superiors.”

Yet Commonweal reported:

“Kasper: Sometimes the CDF views things a bit narrowly. Aquinas was condemned by his bishop. So Johnson is in good company.”

(Commonweal adds:”this is more or less a direct quote”) Earlier in the interview, Kasper was quoted to have said that he “esteems” Johnson and Fiorenza

It sure sounds like he is addressing Johnson’s theology here and the relations with the CDF. Kasper further asserts that he – and his audience – could not have known anything of Cardinal Mueller’s specific criticisms of Johnson because they were published that day. Why that would be the case is unclear to me – particularly since Cardinal Mueller’s remarks had been given as an address to the Leadership Conference on April 30 and had been reported before the interview in the evening.

Moreover, he doesn’t deny at all the most outrageous of his assertions made during his promotional tour: that the Church does not opposes birth control, or that Pope Francis believes 50% of all marriages are invalid. It is all very similar to the endless Vatican “clarifications” of Pope Francis’s remarks.

More HERE – this Wednesday at the Church of the Ascension.

From the program notes of Dennis Keene:

“During the Renaissance, English composers created a huge body of absolutely magnificent choral music – a repertory that held its own against any European country of the period. And, in my opinion, this body of music represents the absolute summit of musical creation in England’s entire history. Furthermore, there is an almost limitless variety among these pieces: profound, soaring Latin motets and masses, brilliant virtuoso pieces, straight-to-the-point communicative settings of English texts, and so forth. I have chosen some of the greatest masterpieces of the two giants of the period, Tallis and Byrd, and a huge variety of works by many other composers.

Our program begins right off with some of the very greatest works of the period: Latin motets of Thomas Tallis. As musician at the Chapel Royal in London from 1543 until his death in 1585, Tallis provided music for four successive British monarchs. During his lifetime the church in England changed back and forth between Roman Catholicism and Anglicanism. Like Byrd, Tallis wrote magnificently for whichever church was in power at the time, while remaining himself a life-long Roman Catholic.”

(I would point out that Byrd at least wrote magnificently for the Catholic Religion even when it was out of power.)

12

May

On Friday, May 9, His Emminence Raymond Cardinal Burke addressed the students, faculty and family of Anchor Academy, an independent Catholic school in Norwalk, CT. Afterwards, he greeted and spoke to each faculty member and family individually. He also celebrated the daily 8 am Novus Ordo Mass at St. Mary’s Church, which was attended by the Anchor families.

Students of Cardinal Newman Academy, the high school connected with Anchor Academy, served the Mass.

David Hughes directed the Anchor Academy Scholae at the Mass

Cardinal Burke addresses students and families of Anchor Academy

Cardinal Burke was introduced to all of the faculty members and families

12

May

His Eminence Raymond Cardinal Burke celebrated a Pontifical Low Mass at St. Mary Church, Norwalk, CT on Saturday May 10 at 9 am. We are indebted to Mr. Duncan Anderson for taking these pictures for us.

8

May

By John Lamont

To understand how the Jesuit conception of obedience departed from earlier conceptions, it is helpful to compare it with the teaching of St. Thomas on obedience. The fundamental difference between the two is that St. Thomas considers the proper object of obedience to be the precept of the superior (2a2ae q. 104 a. 2 co., ad 3). Obedience that seeks to forestall the expressed will of the superior does not bear on what the superior wants or thinks in general, but only on what the superior intends to command. St. Ignatius’s lowest degree of obedience, which he does not consider to be virtuous, is thus what St. Thomas considers to be the only form of obedience. St. Thomas holds that St. Ignatius’s alleged higher forms of obedience do not fall under the virtue of obedience at all:

For Seneca says (De Beneficiis iii): “It is wrong to suppose that slavery falls upon the whole man: for the better part of him is excepted.” His body is subjected and assigned to his master but his soul is his own. Consequently in matters touching the internal movement of the will man is not bound to obey his fellow-man, but God alone. (2a2ae q. 104 a. 5 co.)

St. Thomas ‘s point here is that the limitation of the duty of obedience that is admitted by a pagan philosopher to belong to slaves a fortiori applies to the limitation of the duty of obedience in general. The contrast between Seneca and St. Ignatius on this point is striking. St. Thomas does not hold that his limitation on obedience applies only to obedience in natural matters, with religious obedience being excepted.

Religious profess obedience as to the regular mode of life, in respect of which they are subject to their superiors: wherefore they are bound to obey in those matters only which may belong to the regular mode of life, and this obedience suffices for salvation. If they be willing to obey even in other matters, this will belong to the superabundance of perfection; provided, however, such things be not contrary to God or to the rule they profess, for obedience in this case would be unlawful. (2a2ae q. 104 a. 5 ad 3.)

It is thus the case, as noted above, that St. Thomas does not consider obedience to involve the sacrifice of one’s will as such. It can only involve the sacrifice of one’s self-will, which is defined by its adherence to goods that are attractive in themselves but that do not conduce to our ultimate happiness. Nor does he think of obedience as a virtuous form of personal asceticism. He does not hold that obeying a command we dislike is necessarily better than obeying a command we are happy to fulfil. Indeed, since a rightly directed will seeks the common good, a good person will be glad to carry out any suitable command, since such commands and obedience to them both exist for the sake of the common good.

Obedience does not for St. Thomas occupy the central moral role that it does for Counter-Reformation theologians. He does not consider that all good acts are motivated by obedience to God, because he considers that there are virtues the exercise of which is prior to obedience – such as faith, upon which obedience depends. Nor does he consider that the essence of sin consists in disobedience to God, or even that all sin involves the sin of disobedience. All sin does indeed involve a disobedience to God’s commands, but this disobedience is not willed by the sinner unless the sin involves contempt of a divine command – i.e., involves a will to disobey the command in addition to a will to do the forbidden act. He asserts that ‘when a thing is done contrary to a precept, not in contempt of the precept, but with some other purpose, it is not a sin of disobedience except materially, and belongs formally to another species of sin’ (2a2ae q. 104 a. 7 ad 3). Obedience is simply an act of the virtue of justice, which is motivated by love of God in the case of divine commands and love of neighbour in the case of commands of a human superior. These loves are both more fundamental and broader than obedience.

In addition to his transformation of the traditional conception of religious obedience, St. Ignatius was responsible for another innovation that revolutionised the relation of superior to inferior in the religious life. This was his introduction of a new conception of the manifestation of conscience. Opening one’s heart to one’s spiritual father, and revealing one’s sins, trials, and tribulations, was an ancient practice in the monastic life: it was recommended by St. Anthony himself.10 This practice originally had three characteristics; it was a voluntary act on the part of the person manifesting their conscience, it was directed at a spiritual father who was chosen purely for his wisdom in guiding souls, and its purpose was the growth in holiness of the person making the manifestation.

St. Ignatius rejected these characteristics. He not only encouraged but required the manifestation of conscience, and he required that the manifestation be made to the religious superior – he made no mention of manifestation to a spiritual father other than the superior. He required that such a manifestation be made every six months, and he directed that all superiors and even their delegates were qualified to receive these manifestations – in contrast to St. Benedict, who limited the recipients of the manifestation of conscience to the abbot and a few selected spiritual fathers in the monastery. Finally, instead of restricting the purpose of the manifestation of conscience to the spiritual well-being of the manifestee, the superior was not only permitted but required to use the knowledge of his subordinates gained through the manifestation of conscience for the purposes of government. The manifestation of conscience was much broader and more intrusive than the chapter of faults in monastic communities, which limited itself to external actions that contravened the rule, or even than the necessary extent of self-revelation in the confessional. It included ‘the dispositions and desires for the performance of good, the obstacles and difficulties encountered, the passions and temptation which move or harass the soul, the faults, that are more frequently committed … the usual pattern of conduct, affections, inclinations, propensities, temptations, and weaknesses.’11 It should be underlined that the making of a full manifestation of conscience of this kind was impressed upon the inferior as a grave religious duty.

The overweening power that this practice gives to the superior needs no underlining. The ancient religious orders (such as the Dominicans, Franciscans, and Carmelites) resisted the introduction of an obligatory manifestation of conscience on St. Ignatius’s model, but many modern religious institutes adopted it. The abuses of the practice were so severe that the Holy See eventually had to forbid it. Leo XIII’s decree Quemadmodum banned the practice for lay institutes of men and all religious congregations of women in 1890, and it was banned for all religious by canon 530 of the 1917 Code of Canon Law (the Jesuits, however, were permitted to preserve it by a special decree of Pope Pius XI).12 By this time, however, the practice had had several centuries to leave its mark on the understanding of authority and the psychology of superiors and subordinates within the Church.

There is probably a connection between liturgical practice and the Jesuit conception of obedience as well. The liturgical prayer of the Church is principally composed of the Psalms. Any reader of the Psalms will notice that they are full of what by Counter-Reformation standards is insubordinate language towards God; complaints, demands, criticisms, unsolicited advice, and reproaches. They are not compatible with a spirituality in which the Jesuit conception of obedience plays a central role. Accordingly the Counter-Reformation came to treat the recital of the Divine Office as important largely because it was a task that must be completed under pain of mortal sin. The spiritual life of laity and religious came to be focused instead on devotions, which did not pose this problem. It would be interesting to pursue the question of how far a tyrannical conception of authority influenced post-Counter-Reformation devotion and religious art. One may speculate that the feminised chinless portrayal of Christ, and the sickly sentimentality, that characterised this period, were an attempt to balance the fear and aversion produced by the perception of Christ as a tyrant that would inevitably follow from belief in his supreme authority.

The Counter-Reformation Church thus wholeheartedly adopted the Jesuit understanding of obedience, and extensively practiced the Jesuit method of manifestation of conscience. The effect of this scarcely needs explaining. The Jesuit understanding of authority was a tyrannical one, since it located authority in the will of the superior rather than in the law. Of course, the expositions of this understanding of authority always insisted that it did not extend to commanding sin, but this limitation did not have much practical import. The relevant understanding of a sinful command was more or less limited to grave and clear violations of the Decalogue, and the unjust commands of authority are rarely ones that insist on crimes of this sort; such crimes are not the sort of thing that unjust authorities usually have an interest in commanding. Some expositions of the Ignatian conception of obedience, indeed, described obedience to an order than one suspects but is not certain to be illicit as an especially high and praiseworthy form of obedience.13

To a tyrannical understanding of authority necessarily corresponds a servile understanding of obedience, where the object of obedience is not the law as understood by the reason, but the pure will of the superior untrammelled by the will or intelligence of the subject. Ignatian thought and practice not only upheld a servile understanding of obedience, but provided a uniquely effective method of producing such obedience. The follower’s independent will and intellect are deliberately annihilated as far as is humanly possible, and this is done not only by external pressure, but also by a far more effective means – that of enlisting the follower’ own will in the process, through getting the follower to believe that this annihilation is a religious duty, and indeed is the highest form of holiness. The Ignatian form of manifestation of conscience provided the perfect means of implementing this process. By leaving the the subordinate with no thoughts or desires independent of the superior’s will, it provided a means of thought control that surpassed anything described by George Orwell. It was no accident that totalitarian leaders such as Lenin and Heinrich Himmler admired and emulated the Jesuits.

A number of objections are liable to be raised against this indictment of the Jesuit theory of obedience. Has not Jesuit spirituality in general, and the Constutions of the Society of Jesus in particular, been given the authoritative approbation of the Church? Have the Jesuits not produced many saints and done great work for the Church, something that could hardly have been produced by a tyrannical and thus morally objectionable method of formation? Was St. Ignatius himself not great saint, and an outstanding leader whose methods were not in fact tyrannical ones? Have not Jesuits in the past shown a high level of ability and initiative, something that is incompatible with a method of formation that is a form of brainwashing and breaks the mind and will?

As far as the approbation of the Church goes, it can be pointed out that the essence of the spirituality of St. Ignatius is contained in his Spiritual Exercises. These are distinct from the Constitutions of the Society and his other writings on obedience, and are the spiritual work of St. Ignatius that has been singled out for approbation by the Church. They do not however contain the teachings of St. Ignatius on obedience that are criticised here, and in fact lay stress on reflection and conscious action. The Constitutions of the Society have been approved by the Church as the basic regulations governing the structure and functioning of the Society. This approval thus bears on the Constitutions as a regulatory structure for the Society; the reflections on obedience in the Constitutions do not form part of this regulatory structure, and hence are not the objects of the approbation of the Constitutions by the Church.

When it comes to the achievements of the Society of Jesus, it should be remembered that notwithstanding the heroic witness of a number of Jesuit martyrs, the principal achievement of the Jesuits – the thing they were really good at, and that enabled them to make a decisive contribution to the Counter-Reformation – was running secondary schools. It was the Jesuit schools that enabled them to turn the tide in favour of the Church in a number of European countries. A defective understanding of authority and obedience did not have too much scope for action in these schools. For one thing, they were run according to a detailed and uniform program that did not leave much scope for tyrannical initiatives on the part of the superior. For another, they had the essential test of direct, immediate success or failure at their stated object, which is a main curb in practice on tyranny and servility. Educational success was immediately apparent, and meant the schools would flourish; educational failure was equally apparent, and meant that they would lose their pupils. Finally, the difficult and humbling side intrinsic to all successful teaching was not propitious for the characteristics that mark those who enjoy and practice tyranny or servility. Neither the servile nor the tyrannical have the authority needed to teach large numbers of adolescent boys. When it came to the main apostolic activity of the Jesuits, a literal understanding of St. Ignatius’s teachings on obedience was thus destined to largely remain a dead letter. Unfortunately this was not the case with other orders and other apostolic pursuits in the Church of the Counter-Reformation.

There are more considerations that need to be kept in mind when considering the successes of the Society of Jesus in general. The Society does seem to have ended up by attempting to train its recruits according to a servile conception of obedience, at least initially, but the calibre of Jesuit recruits led to this formation producing a result that was different from its ostensible purpose. The Society was very selective in the men it admitted, insisting on ability and intelligence that were far above average, and the men admitted were generally given substantial tasks to do. Servile obedience is inculcated by subjecting the inferior to humiliating, pointless and unpleasant tasks, to a degree intended to break their will and self-respect. With individuals of strong will and high intelligence, however, this process can fail of its purpose. In such a case, what it produces is great toughness and endurance, together with rigorous self-control and the capacity to disguise one’s thoughts and emotions. Such a process is often used in the initial stages of military training, in order to produce just these qualities. When this toughness and self-control has been elicited, however, the character of military training is changed to foster the qualities of initiative and intelligence that are required for successful performance.The demand for success in important tasks virtually requires subordinates to show initiative, and superiors to exercise actual leadership. Jesuits who lived up to the servile theory on obedience would thus tend to fail at the tasks required of them, and to suffer as a result. The need for success in the important tasks undertaken by the Society demanded a mitigation in practice of the tyrannical theory of authority.

It seems that the Jesuits in fact took this approach to obedience, appropriately so given St. Ignatius’s military background. Their training came to be valued not simply for its capacity to produce obedience, but even more for the traits of endurance, self-control, and dissimulation of the emotions that it inculcated – the Jesuits came to be recognised as distinguished above all others for their capacity to master anger. These traits are extremely useful in worldly activities, and explain much of the success of the Jesuits in worldly affairs, although their usefulness in producing holiness is open to question.

These mitigating factors depended however on the character of the Jesuits as a carefully selected elite. They could not obtain for the Church as a whole, and they did not do so. For the great majority of Catholic priests and religious, the Jesuit conception of obedience and the Jesuit method of manifestation of conscience tended to produce what they were intended: subordinates who believed that they owed servile obedience to their superiors, that they should surrender their will and intelligence to the people above them, and that in so doing they were doing God’s will and growing in holiness: and superiors who believed that their commands were the will of God, and that any resistance to these commands by their subordinates was rebellion against God himself.

As for the wisdom, sanctity, and achievements of St. Ignatius, we should distinguish between the meaning of St. Ignatius’s writings on obedience when considered in abstraction from their original context, and the meaning that St. Ignatius can be judged to have ascribed to them when we look at the context of his own purposes and actions. In the light of this context, it seems that what St. Ignatius had in mind in his writings on obedience was the idea that the subordinate should not simply carry out explicit commands, but should grasp the plan of the superior that the commands were intended to implement, and should accept and enthusiastically carry out that plan. Such an approach to the superior’s purposes was necessary for the tasks that he intended the Jesuits to carry out, because these tasks generally required independent action where regular recourse to the superior’s instructions could not be available. It is in general the approach that subordinates must take to carry out any substantial task properly. However, in expressing this idea St. Ignatius was handicapped by the deficient understanding of law that was accepted in his time. As we have seen, this understanding was not St. Thomas’s conception of a law as a rational plan to achieve some good. Law was instead conceived of by the philosophers and theologians with whom St. Ignatius was familiar as simply a set of commands. In his writings on obedience St. Ignatius was trying to get across the idea that obedience to the law in this sense – obedience simply to the content of the explicit orders of the superior – was not sufficient, and that an understanding of and identification with the superior’s purposes was necessary. He did not however have at his command an idea of a law that could exist in the superior’s mind, be distinct from the superior’s beliefs and purposes generally, and be rationally appropriated by the subordinate. He was therefore induced to convey his meaning by calling for an identification with the superior’s personal intentions and beliefs, without making a satisfactory distinction between the superior’s plan and general objectives as directed to the common good, and his other beliefs and goals. We can draw a comparison here with St. John of the Cross; just as St. John would not have accepted the unreasonable conclusions that followed from his ascetical teaching, and did not put these conclusions into practice, so St. Ignatius did not intend the unreasonable applications of his writings on obedience. He was simply betrayed into unreasonable positions, as was St. John of the Cross, by the philosophical assumptions of his age, from which he was not able to emancipate himself. We might also see his personal struggles as an influence on his doctrine of obedience; originally vainglorious and ambitious, and always attracted to ruling and taking the initiative, he would have found the attempt at a total surrender of mind and will to another a useful tool for combating his dominant faults.

The problem was that the meaning of St. Ignatius’s writings on obedience taken in the context of his actions and purposes, and the meaning of these writings when considered on their own, were not identical; and it was the latter meaning, not the former, that was generally accessible to, and generally accepted by, the Church of the Counter-Reformation. It is true that intelligent spiritual writers could interpret the Jesuit theory of obedience in an acceptable way. For example, Dom Paul Delatte, in commenting on the Rule of St. Benedict, writes of the Rule’s demand for obedience that

Obedience so described is a far different thing from the obedience that reproduces the passivity and inertia of a corpse, or the unthinking docility of a stick that we brandish in our hands. It is said that a good commander ought to have his forces well in hand, so as to get from them with spirit and unity the maximum efficiency at the exact moment it is needed. So it is with the obedient soul … When the masters of the spiritual life use these comparisons they merely wish to express the perfect pliancy of the obedient soul, dead to its own will.14

Dom Delatte was however writing from within the Benedictine tradition, which had its own well-articulated understanding of obedience that could be and was used to interpret St. Ignatius’s writings in a positive sense. But the usual practice was to take St. Ignatius’s words literally, in a sense that commended a tyrannical understanding of authority.

We find this, for instance, in Alphonsus Rodriguez S.J.’s Practice of Perfection and Christian Virtues. This work, the most widely read manual of ascetic theology of the Counter-Reformation, was published in Spanish in 1609, and went through many editions in many translations – over sixty in French, twenty in Italian, at least ten in German, several in English. It was required reading for Jesuit novices up to the Second Vatican Council. In his proposed examination of conscience, Fr. Rodriguez (who is not to be confused with St. Alphonsus Rodriguez) requires the penitent

II. To obey in will and heart, having one and the same wish and will as the Superior.

III. To obey also with the understanding and judgment, adopting the same view and sentiment as the Superior, not giving place to any judgments or reasonings to the contrary.

IV. To take the voice of the Superior … as the voice of God, and obey the Superior, whoever he may be, as Christ our Lord, and the same for subordinate officials.

V. To follow blind obedience, that is obedience without enquiry or examination, or any seeking of reasons for the why and wherefore, it being reason enough for me that it is obedience and the command of the Superior.15

Rodriguez praises obedience – as he understands it – in illuminating terms.

One of the greatest comforts and consolations that we have in Religion is this, that we are safe in doing what obedience commands. The Superior it is that may be wrong in commanding this or that, but you are certain that you are not wrong in doing what is commanded, for the only account that God will ask of you is if you have done what they commanded you, and with that your account will be sufficiently discharged before God. It is not for you to render account whether the thing commanded was a good thing, or whether something else would not have been better; that does not belong to you, but to the account of the Superior. When you act under obedience, God takes it off your books, and puts it on the books of the Superior. … so the Religious, living under obedience, composes himself to sleep – that is to say, he has no trouble or care about what he is to do, but goes his way to heaven and perfection. Superiors see to that, they are the captains and masters of the ship. … this is the blessing which God has given to the Religious who lives under obedience, that all his burden is thrown on the shoulders of his Superior, and he lives at ease and without care whether this be better or that. This is one of the things that greatly move virtuous folk to live under obedience and enter Religion, – to be rid of the endless perplexities and anxieties that they have there in the world, and be sure or serving and pleasing God. … If I were there in the world and desired to serve God, I should be troubled and in doubt whether I eat too little or too much, sleep too much or too little, do too little or too much penance … but here in Religion all these doubts are cleared away, for I eat what they give me, I sleep at the time appointed, I do the penance they assign me. 16

Rodriguez adds that ‘not only in spiritual matters, but also in temporal, this is a life very restful and void of care. Like a passenger in a well-victualled ship, a Religious has no need to attend to his own necessities.’17

One could not give a plainer exposition of a servile notion of obedience. Rodriguez’s position draws the logical conclusion from a literal understanding of St. Ignatius’s writings on obedience. If a subordinate entirely abandons the activity of his own mind and will when presented with the order of a superior, it is indeed the case that he surrenders all moral responsibility for the execution of the order, and the responsibility is transferred entirely to the superior who gives the order. That is because moral responsibility requires the functioning of one’s intellect and will; if this functioning is legitimately abolished in the case of a superior’s order, responsibility for the execution of the order is abolished as well. The fact that the abandonment of this functioning is presented as legitimate and indeed as obligatory is the key to this logical implication. If the functioning of one’s mind and will is abandoned illegitimately, one does not lose all moral responsibility for the acts that one performs as a result of their abandonment. But if this abandonment is legitimate, as Rodriguez claims it is, moral responsibility is indeed necessarily suspended.

In drawing this conclusion, Rodriguez goes farther than St. Ignatius. The absence of this conclusion in the writings of St. Ignatius is what makes it possible to give a pious interpretation to his views on obedience, and to assert that his writings need not be read as an endorsement of a tyrannical understanding of authority and a servile understanding of obedience. With Rodriguez such an interpretation is ruled out, and these understandings of authority and obedience take undoubted possession.

Like other writers, Rodriguez makes the usual exception for obedience to commands that are manifestly contrary to the divine law. But this exception is not something that has much practical reality. Internalising and practicing the Jesuit notion of obedience is difficult, and requires time, motivation, and effort. When it has been done successfully, it has a lasting effect. Once one has destroyed one’s capacity to criticise the actions of one’s superiors, one cannot revive this capacity and its exercise at will. Following the directive to refuse obedience to one’s superiors when their commands are manifestly sinful then becomes psychologically difficult or even impossible – except perhaps in the most extreme cases, such as commands to murder someone, which are not the sort of sinful commands that religious superiors often have an interest in giving in any case.

There is an explicit appeal to the wisdom and goodness of superiors in this doctrine of obedience. This appeal however ignores the characteristic effects of the exercise of tyrannical authority, which are no less deep – perhaps deeper – than those of the practice of servile obedience. Such authority has an intoxicating effect, producing overweening pride and megalomania. Superiors in the grip of these vices become both prone to giving unjust orders, and incapable of conceiving of themselves as sinful or mistaken.

Rodriguez is especially interesting in his description of the principal appeal of a servile conception of obedience to the subordinate (its appeal to a superior needs no explaining). He states in the plainest terms that this appeal lies in the abdication of all adult responsibility, along with the worries that inevitably accompany it. The ruinous effects of attracting to the clerical state people who seek avoidance of adult responsibility, and the material security of passengers in a well-victualled ship, extend much farther than the overthrow of the rule of law in the Church.

This servile conception of obedience remained the standard one into the twentieth century. Adolphe Tanquerey, in his widely read and translated (and in many way excellent) work Précis de théologie ascétique et mystique,18 could write that perfect souls who have reached the highest degree of obedience submit their judgment to that of their superior, without even examining the reasons for which he commands them.19 The Jesuit conception of obedience did not remain a peculiarity of the Society, but came to be adopted by the Counter-Reformation Church as a whole. This was due to the prestige of the Society and the attractiveness to religious superiors of the nature of the obedience held up as a model, and also to the plausibility of the conception given the philosophical assumptions noted above. This conception of obedience was completely dominant in the many foundations of the Counter-Reformation, which, unlike the Benedictines, lacked traditions of their own to counteract a literal reading of St. Ignatius. It was also prevalent in the new institution of the Counter-Reformation seminary. We can see an manifestation of this prevalence in the Treatise on Obedience of the Sulpician Louis Tronson, which gave St. Ignatius’s teaching and writings as the summit of Catholic teaching on obedience. The Sulpician adoption of the Jesuit conception was particularly important because of their central role in the training of priests in seminaries from the 17th century onwards. The seven years of seminary training meant that the tyrannical understanding of authority and servile understanding of obedience conveyed by this training was deeply ingrained in those who went through it.20

As a result, this was the understanding conveyed to the laity. Its effect on the laity was different from its effect on the clergy. The laity could never hope to acquire authority, so the traits needed to rise in a tyrannical system were not produced in them. What happened instead was that the laity were infantilised in the religious sphere of their lives. This infantilisation can be observed in religious art and devotion, especially from the 19th century onwards, and in the willingness to give blind obedience to the clergy. It had of course a certain attraction; there is a comfort in relapsing into childhood in some sphere of one’s life, and handing over deliberation, decisions, and adult responsibility to one’s superiors. This attraction is the basis of the appeal of religious cults and totalitarian states. The Catholic laity did not have to endure tyrannical authority in every sphere of their lives, so this comfort was all the more appealing to them; it did not have the accompanying cost of total servility that the clergy had to pay.

It was thus the literal, tyrannical understanding of St. Ignatius’s writings on obedience that had come to be accepted by the Counter-Reformation Church. The enormous chaos that followed the Second Vatican Council is an indication of this acceptance. It revealed a widespread alienation from Catholic teaching and tradition among priests and religious, the majority of whom either gladly rejected what they had been taught to consider true and holy or left the religious life altogether. This was a consequence of identifying this teaching and tradition with the tyrannical regime under which they had been formed. The resulting hatred and alienation was greatly aggravated by the fact that this regime was largely incapable of communicating a real understanding of Catholic tradition in the first place, because such an understanding requires a mature exercise of intellect and will – precisely the things that religious formation was designed to extirpate. As a result there was little or no real grasp of the tradition to counteract the reaction against the generally accepted conception of it. Indeed such a real grasp often made a priest or religious suspect in the eyes of ecclesiastical authority, since it required this mature and independent exercise of thought and insight – as is the case with all substantial traditions. The tragicomic history of John Henry Newman’s career in the Catholic Church is a good illustration of this suspicion. Newman’s actual thought was ferociously reactionary in nature, but because he had arrived at his positions by himself, he came under the suspicion of ecclesiastical authorities (who were in fact often more liberal than himself in their ideas), and was held up as a hero by modernists whose whole lives were condemned by his writings.

As for the laity, their indoctrination in blind obedience made them willing and even proud to follow disaffected clergy when ordered to reject the liturgy and teachings that they had previously been told were sacred and inviolable. The lack of Catholic initiative by the laity in the preconciliar period is also to be explained by this infantilising formation. It has long been noted that converts to the faith, at least in the English-speaking world, made a disproportionately large contribution to Catholic thought and culture. This was inevitable given the formation that cradle Catholics had received.

Formation in tyrannical authority and servile obedience inevitably fostered undesirable characteristics in the priests who exercised authority over the laity, and thus produced hostility to the clergy. It is significant that the term that came to be used for opposition to the Catholic Church in Europe was ‘anticlericalism’. In its literal meaning, the word ‘anticlericalism’ is quite distinct from opposition to Catholicism, since it simply means antipathy to the Catholic clergy. Such an antipathy does not imply rejection of the Catholic faith, and in some circumstances may be quite justified, or even required by fidelity to the Church. Its identification with anti-Catholicism as such was the result of an opportunistic exploitation by unbelievers of the widespread loathing of the clergy, a loathing caused by their practice of a tyrannical conception of authority, together with a genuine identification of the faith with the clergy – an identification fostered by the infantilisation of the laity, which produced the impression that the faith was the property of the clergy as such.

There were of course many factors in the Church that counteracted the effects of the philosophical and practical forces described above; her intellectual traditions with their insistence on learning and philosophy, healthier traditions of spiritual teaching and practice, and the demands of reality itself in the form of the challenges and responsibilities faced by clergy and religious. In the 20th century, however, the forces within the Church promoting a tyrannical understanding of authority and a servile understanding of obedience received decisive reinforcement from two factors.

The first was the promulgation of the Code of Canon Law in 1917. The basic idea of this codification – that of streamlining the canon law of the Latin Church, and making it easier to use – was well-meaning and indeed correct, but the way in which this idea was implemented was fundamentally flawed. The problem with the 1917 Code was that it was a Napoleonic Code, rather than a Justinian Code. When the Emperor Justinian decided to codify Roman law for purposes similar to the ones that inspired St. Pius X, the whole mass of previous Roman legal rulings and decrees were collected together, organised, and purged of obsolete and contradictory elements. They were not however ruled void of authority and replaced by an entirely new body of edicts. The great body of Roman legal tradition was preserved in Justinian’s codification. In the Napoleonic code, in contrast, the previous legal tradition was abolished and entirely replaced by the new and much smaller collection of decrees that made up the code devised by Napoleon and his jurists. The Latin Code of Canon law of 1917 was deliberately designed on the Napoleonic rather than the Justinian model. The massive body of the Latin legal tradition, collected in the Corpus Iuris Canonici, was declared to be of no force. From this point onwards the Latin Church had to operate largely without the benefit of its own legal tradition, on the basis of a legal system modelled on the legislation of a military dictator implementing Jansenist and Enlightenment ideas of law and authority. In addition to the crippling of Catholic legal practice that this involved, the alleged abrogation of the entire Corpus Iuris Canonici was itself of dubious legality, since the canonical tradition of the Church has always been considered to contain substantial elements of sacred tradition. This is recognised by the Oriental Code of Canon Law, which states at its outset that ‘the canons of the Code, in which for the most part the ancient law of the Eastern Churches is received or adapted, are to be assessed mainly according to that law’ (canon 2). It is paradoxical that the Oriental Code should recognise the authority of the Eastern canonical tradition, while the the Latin Code should overthrow the Latin tradition – despite the fact that the Latin tradition is the one that contains most of the rulings of the pope, the highest legal authority in the Church. The 1917 Latin Code thus struck a severe blow at the rule of law in the Church.

The second factor in promoting a tyrannical understanding of authority was the abandonment of the Church’s practical activities in the postconciliar period. The enormous involvement of clergy and religious in education and health was largely shut down along with the religious orders that carried out this involvement. The institutions that had carried out this involvement were handed over to governments or lay organisations, and became Catholic in name only. The direct activity of the Church in preaching and administering the sacraments was also greatly reduced, as congregations shrunk after the Council and continue to decline. The expectation that priests and religious would succeed in carrying out serious work, and the accompanying need for competence and leadership, declined along with the decline in serious work to carry out. The scope for tyrannical exercise of authority was correspondingly widened.

This last factor may seem to contradict the thesis about the dominance of a tyrannical conception of authority in the Church. Do not tyrants seek something to tyrannise over? If the importance and influence of Catholic activities declines steeply, does not their scope for tyranny decline with it?

To answer these questions, we need to understand the dynamics of an organisation that has been dominated for a long time by a tyrannical conception of authority and a servile conception of obedience. The key point is that in a clerical system dominated by these conceptions, the leaders all start off as followers themselves. In this capacity, they learn the skills of the slave for survival and advancement; flattery, duplicity, bullying and humiliation of those beneath them, and concealment. Their promotion from subordinate to superior does not depend primarily on their competence at the tasks they are supposed to perform, but on their capacity to ingratiate themselves with their superiors. The leadership in such a system is thus not selected for its capacity to get things done, and is not generally motivated by a desire to get things done. The dominant motivation is desire to escape the servile position and enjoy the tyrannical position. A collapse of the real activities of the institution does not get in the way of the fulfilment of this desire – if anything it makes it easier, by dispensing with the need for determination and intelligence in the personnel of the institution; these characteristics compete with the skills of the courtier as qualifications for promotion, and make the task of tyrannical leadership a lot more difficult. The deliberate destruction of these activities of the Church was to a great extent motivated by the desire of religious leaders in the Church to free themselves of the encumbrance of real responsibilities, the better to have free range for the arbitrary exercise of their wills.

We have now seen how the members of the Church have been formed to accept a tyrannical understanding of authority and a servile understanding of obedience in religious affairs. This in turn explains why the rule of law does not obtain in the Catholic Church; its leaders do not consider themselves to be subject to the law, and their followers do not see the law as the source of their leader’s authority or as a constraint upon their actions.

There are connections between these causes and the particular form of violation of the law mentioned at the outset of this paper. Scandalous sexual activity on the part of priests is not new in Catholic history; it has occurred during every period in the past when zeal and fidelity in the Church has diminished. What is new, however, is the character of this activity. Previous scandal largely involved concubinage and casual fornication by priests. The scandals of the past sixty years, however, have been of a different character; involvement with adolescent boys has been much more significant than in any previous period of corruption on the part of the clergy. It is not of course that such involvement was absent in the past; it is that it was not the characteristic form that clerical sexual misbehaviour took. This new development is a result of the fact that these forms of sexual abuse are closely connected with narcissistic personality types, and a social structure based on tyranny and humiliation both forms and selects for this type of personality.

The abandonment of the rule of law in the Church is only one of the manifold consequences of the Jesuit conceptions of authority and obedience. It is impossible to even attempt a description of all of these consequences. I believe however that these consequences put together are one of the most serious problems that the Church suffers from today; if we restrict our consideration to internal problems, it is likely that they are the most serious one. The single effect of the overthrow of the rule of law in the Church indicates that this is the case, and demonstrates the urgency of rejecting these conceptions of authority and obedience, and replacing them by the traditional ones that enlist, rather than destroy, the free cooperation of mind and will.

8

May

By John Lamont

(Lecture given in New York on Friday, April 4, 2014)

The terrible crimes committed against minors by Catholic priests and religious have constituted a dreadful crisis for the Catholic Church over a period of many years. There is however one aspect of this crisis that has not attracted all the attention it should have. This is the failure of the rule of law in the Church with respect to these crimes. Until November 27, 1983, the law in force in the Latin Church was the 1917 Code of Canon Law. Canon 2359 §2 of this code decrees that ‘if clerics have committed an offense against the sixth commandment of the Decalogue with minors under sixteen years of age … they shall be suspended, declared infamous, deprived of every office, benefice, dignity, or position that they may hold, and in most grievous cases they shall be deposed.’ This canon declares that sexual abuse of minors must be punished by specific penalties.1 If it had been enforced, the grave crisis of sexual abuse in the Church would never have occurred, because the key to this crisis – the transferring of guilty priests to new locations where they could abuse again – was ruled out by the penalties imposed. But at some point after the Second World War, this canon ceased to be applied. Clerics who sexually abused minors were not canonically tried and punished, regardless of the severity of their crimes and the strength of the evidence against them. A number of proximate reasons have been offered for this state of affairs – aversion to legalism, lack of understanding of canon law on the part of the responsible authorities – but none of these proximate reasons could have obtained without an underlying indifference to the enforcement of the law.

This is not simply a matter of laws being broken, something that will always happen. It is rather a matter of there being no effort to stop them being broken on the part of authority; of no-one considering that the lack of enforcement of these laws is especially unusual, let alone a grave evil in itself; of there being no identification of the lack of enforcement of the laws as a principal reason for the flourishing of the evils they are designed to suppress; of there being no call for the enforcement of the law as the proper and indispensable path to the suppression of these evils. It would be possible to show that the same thing has happened in other areas of canon law, but that would take us too far afield; the gravity of this problem on its own suffices to establish that the rule of law does not exist in the Catholic Church.

This paper has the object of investigation how this extraordinary situation came into being. The essence of the explanation that will be proposed is that the rule of law came to be abandoned because of the adoption of a tyrannical understanding of authority and a slavish understanding of obedience in the Latin rite of the Catholic Church. A tyrannical understanding of authority considers the rightful exercise of authority to lie purely in the will and command of the superior, and the corresponding servile understanding of obedience sees obedience as consisting purely in conformity to the will of the superior, rather than in obedience to the law and the underlying common good that produces, defines, and limits the power of a ruler. These understandings have rendered the idea of the rule of law in the Church undesirable and indeed incomprehensible for the clerics who have the charge of ruling the Church, and to some extent for all Catholics.

An external cause influencing the acceptance of a tyrannical notion of authority was the growth of absolutist conceptions of the state in the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance, a growth itself fostered by the revival of Roman law, with its absolutist conception of the supreme ruler as himself above the law. The need for the Catholic Church to ally itself with Catholic absolutist states during the Reformation impeded any criticism of such a conception of authority, and the formation of the outlook of Catholics by these states fostered acceptance of this conception.

The most important causes were however ones that were internal to the Church. These can be divided into philosophical and practical causes. The philosophical causes were the development of notions of law, freedom, justice, and authority that had their roots in the Middle Ages, but that came to be treated as undoubted axioms by the theologians of the Counter-Reformation. These notions and their consequences have already been discussed by scholars, most notably by M.-M Labourdette, Michel Villey, and Servais Pinckaers.2 An outline of the findings of these scholars is necessary for our topic, although unavoidably inadequate. Their basic finding is that St. Thomas’s modified Aristotelian understanding of these notions was rejected, and replaced by quite different views that were largely of Scotist and nominalist origin. To understand these views and their shortcomings, we will proceed by describing them and contrasting them with St. Thomas’s positions.

It is somewhat paradoxical to say that the Scotist conception of freedom of the will as consisting in liberty of indifference was a fundamental basis for the development of a tyrannical notion of authority, but it is nonetheless true. In St. Thomas’s thought, a rational action, or a voluntary action – the two expressions mean the same thing – is an action that proceeds from knowledge of the good sought in the action. Since the good is the ultimate motivating attraction behind such action, it follows that there is something that the will wills of necessity. This is the good – the final cause – of the agent, a final cause that corresponds to the agent’s essential nature. All goods are sought for the sake of attaining the agent’s final end. Of course, not all goods that are sought do really offer this attainment. Except in the case of rational beings who are enjoying the Beatific Vision, it is possible for the practical intellect to be ultimately directed towards a good or goods that do not in fact realise the agent’s final end. However, even these goods are sought because the agent considers them to offer ultimate and complete satisfaction, and no good that does not have some relation to the actual final end of man can be sought voluntarily. So it is the case that the will wills something of necessity. It always wills to attain complete satisfaction; it always wills things that resemble to some extent what will actually satisfy; and if it enjoys the Beatific Vision, it always wills its real ultimate end, which is enjoyment of the vision of God.

Beginning with Duns Scotus, a different conception of freedom of the will came to be accepted by Catholic theologians. This is the conception of freedom as consisting in liberty of indifference. According to this conception, an act is free only if the agent has it in his power to either will or not will to do it. It follows from this account of freedom that there is nothing that the will wills of necessity. This means that obedience must necessarily involve some surrender of the will. Whenever a command is given, there must always be the possibility of the person commanded choosing to do otherwise; if this possibility is lacking, obedience to the command is not free, and thus is not really obedience.

The adoption of liberty of indifference led to a fundamental change in the understanding of law. St. Thomas’s claim that the good is willed necessarily is expressed by his description of the first principle of practical reason, which is ‘Do good and avoid evil’. The practical reason is the rational faculty that gives rise to voluntary actions, as opposed to the theoretical reason which produces the beliefs assented to by the intellect. The first principle of practical reason is thus the principle that directs all voluntary action whatsoever. Because it directs all action to pursue good and avoid evil, it expresses the fundamental orientation of the will towards the good, and indeed defines what it is to have a will on St. Thomas’s view. It does not suffice to direct all action towards objects that are entirely good, unless the agent has a direct and certain knowledge of the good for man, because such a direct and certain knowledge of the good is necessary to remove all attraction from options that are good in some respect but not good absolutely speaking. That is why the principle does not exclude the possibility of sin; only those who enjoy the Beatific Vision have the direct and certain knowledge of the good that can exclude wrongdoing. But it means that even sinful actions are not chosen because they are sinful, but for the sake of some good that is believed to characterise them.

However, if the will possesses liberty of indifference, St. Thomas’s account of the first principle of practical reason cannot be correct. Its directive to seek the ultimate good of man cannot be the principle for all voluntary action, because the will wills nothing of necessity, even the ultimate good of the agent. The meaning of this principle was therefore changed by the theologians of the Counter-Reformation. Instead of being the first principle for all voluntary action, it became the rule governing all moral action. As a result, the question of why we should obey this principle can arise. The answer can be found in Suarez; we should obey it because we are commanded to by our ultimate superior, God. Suarez did not go so as far as William of Ockham, who held that God’s command was the only feature that determined the goodness of good actions and the badness of bad actions. He thought that nature on its own determined what was good, but that this determination did not suffice for obligation. The fact that something is good provides a reason for doing it, in his view, but still leaves open the question ‘why do we have an obligation to do what is good?’ Suarez thought that the only answer to this question – the extra factor needed to transform mere goodness into obligation – was a divine command. Because only God’s authority creates an obligation to obey, all other authorities derive their right to obedience from a divine command to obey them. St. Thomas held that we obey both human and divine authority because it is good to do so. This is impossible in Suarez’s system.

We can see how in this scheme obligation, and hence obedience, are not ultimately rooted in the will of the individual obeying. Obedience cannot be an implementation of the fundamental orientation of the will towards happiness, as it is for St. Thomas in the case of a good person who obeys as an act of justice. It must be an external imposition from some other will. Since rights consist in an entitlement to act freely within some sphere, obedience and rights become mutually exclusive – as do obedience and freedom, contrary to the idea that God’s service is perfect freedom3. We are in a universe where the will and freedom of man and God are by nature mutually exclusive – what God gains, man must lose. Admittedly the natural good is not denied in this system, as it for Ockham, but the element of authority in this system – the element from which the duty of obedience emerges – is solely based on conformity to the will of the superior. Obedience thus essentially consists in submission to the will of another.

We can see the assumption of this fundamental antagonism between the divine and human wills in the famous ascetic counsel of St. John of the Cross:

Strive always to prefer, not that which is easiest, but that which is most difficult;

Not that which is most delectable, but that which is most unpleasing;

Not that which gives most pleasure, but rather that which gives least;

Not that which is restful, but that which is wearisome;

Not that which is consolation, but rather that which is disconsolateness;

Not that which is greatest, but that which is least;

Not that which is loftiest and most precious, but that which is lowest and most despised;

Not that which is a desire for anything, but that which is a desire for nothing;

Strive to go about seeking not the best of temporal things, but the worst.4

Literally interpreted, this spiritual counsel can only be suitable for souls in hell, who of course will not avail themselves of it. That is because unless one’s will is completely fixed on evil to the exclusion of any good desires at all, as happens only with damned souls, on at least some occasions one will prefer doing what is good to doing what is bad. Under such circumstances, doing what is less pleasant rather than doing what is more pleasant will mean acting badly, and following St. John of the Cross’s counsel will lead one to sin. The reason why St. John of the Cross ignores this obvious failing in his position – and why this failing is scarcely ever given as an objection to his ascetic doctrine – is that he and his readers have taken for granted the fundamental opposition between the human and the divine will that is implied by liberty of indifference. His teaching shows the influence of this conception of the will on the Counter-Reformation outlook in general.

Connected with this transformation of the idea of obligation is the transformation of the understanding of rights that has been investigated by Michel Villey. For St. Thomas, the term ‘ius’ – later to be translated as ‘right’ – refers to a thing; to a certain distribution of material or other goods and evils, which conforms to the demands of justice. These demands are determined by the just proportion set out by Aristotle in book 5 of the Nicomachean Ethics, in which members of a society receive the rewards and punishments that are due to them. Human societies are natural entities with natural components – such as families, property, laws, religion – whose function is to cooperate in attaining their good. The contribution of members of society to the whole whether for good or for evil, a contribution constituted by their place and activity in these natural structures, determines what is due to them. Justice is the virtue of rendering to everyone their due – goods, obligations, or punishments, as the case may be; and this due is a relation between persons and things, a relation that justice preserves or brings into being.

This understanding of justice fell afoul of William of Ockham’s nominalist metaphysics. Ockham held that only individual substances exist. In consequence he rejected the reality of relations, and the reality of entities that were not substances, but had substances as their components. The objective right of Aristotle and St. Thomas is kind of relation, and the human society that founds this objective right is a whole that is made up of substances but is not itself a substance, so objective right could not be accommodated in Ockham’s philosophy. In its place he introduced what Villey calls a subjective right. This is a monadic property of a single individual – a particular sphere of action in which a person is entitled to act just as he pleases without interference from anyone. It is a scope of action for the individual’s liberty of indifference. Although Ockham’s nominalism did not meet with complete acceptance, his understanding of subjective right eventually achieved a complete victory – at least in theory – over the notion of objective right. This meaning, which Villey terms ‘subjective right’, came to displace the older meaning of ‘ius’ as objective right. With this displacement came a fundamental redefinition of the understanding of justice. This virtue came at first partially and then completely to be understood as meaning the respect of the subjective rights of individuals. Your rights are the area within which your will can operate freely; a constraint on your range of choices, conversely, is a constraint on your rights. Suarez, who was the principal Catholic legal theorist of the Counter-Reformation, defined rights as subjective rights, and understood laws as limitations on these rights that are based on the commands of the legislator. Here we have reproduced in the sphere of law and justice the competition between two mutually exclusive wills, that of the superior and that of the subordinate, in which what is gained by the one is lost by the other. What has been contributed by the replacement of objective right by subjective right is the elimination of the competing understanding of justice as based on desert, and distinct from the command of a superior.

The Counter-Reformation understandings of will, freedom, authority, and law thus both permitted and fostered the emergence of a tyrannical notion of authority and a slavish notion of obedience, whereas St. Thomas’s understanding of these things firmly excluded them.

However, in order for the tendencies of these philosophical positions to have a deep effect on the Church, they needed to be embodied in practice. This embodiment took place in the conception of obedience that came to be adopted by the Jesuits, and in the methods by which this conception of obedience came to be inculcated and enforced. The source and best expression of this conception is to be found in the writings of St. Ignatius Loyola, particularly in the Constitutions of the Society and in his letter on obedience written to the Jesuits of Portugal in 1553. Its key elements are the following.

1. The claim that the commands of the superior have the force of divine commands, and should be treated as divine commands – provided, of course, that obeying them would not be manifestly sinful; this qualification should always be understood as applying to the Jesuit conception of obedience. St. Ignatius asserted: ‘The superior is to be obeyed not because he is prudent, or good, or qualified by any other gift of God, but because he holds the place and the authority of God, as Eternal Truth has said: He who hears you, hears me; and he who rejects you, rejects me [Luke 10:16].’5 ‘In all the things into which obedience can with charity be extended, we should be ready to receive its command just as if it were coming from Christ our Saviour, since we are practicing the obedience to one in His place and because of love and reverence for Him.’ (Constitutions, part VI, ch. 1).6 This position seems to have received general acceptance in part because of acceptance of the fallacious inference from the premise that God commands us to obey the orders of our superiors, to the conclusion that the orders of our superiors are commandments of God.

2. The claim that the mere execution of the order of a superior is the lowest degree of obedience, and does not merit the name of obedience or constitute an exercise of the virtue of obedience.

3. The claim that in order to merit the name of virtue, an exercise of obedience should attain the second level of obedience, which consists in not only doing what the superior orders, but conforming one’s will to that of the superior, so that one not only will to obey an order, but wills that that particular order should have been given – simply because the superior willed it.

4. The claim that the third and highest degree of obedience consists in conforming not only one’s will but one’s intellect to the order of the superior, so that one not only wills that an order should have been given, but actually believes that the order was the right order to give – simply because the superior (it is supposed) believes this himself. “But he who aims at making an entire and perfect oblation of himself, in addition to his will, must offer his understanding, which is a further and the highest degree of obedience. He must not only will, but he must think the same as the superior, submitting his own judgment to that of the superior, so far as a devout will can bend the understanding.” (Letter on Obedience)

5.The claim that in the highest and thus most meritorious degree of obedience, the follower has no more will of his own in obeying than an inanimate object. ‘Everyone of those who live under obedience ought to allow himself to be carried and directed by Divine Providence through the agency of the superior as if he were a lifeless body which allows itself to be carried to any place and to be treated in any manner desired, or as if he were an old man’s staff which serves in any place and in any manner whatsoever in which the holder wishes to use it.’7 (Constitutions part VI ch. 1).

6. The claim that the sacrifice of will and intellect involved in this form of obedience is the highest form of sacrifice possible, because it offers to God the highest human faculties, viz. the intellect and the will.

‘Now because this disposition of will in man is of so great worth, so also is the offering of it, when by obedience it is offered to his Creator and Lord. … there are, however, many instances where the evidence of the known truth is not coercive and it can, with the help of the will, favour one side or the other. When this happens every truly obedient man should conform his thought to the thought of the superior.

And this is certain, since obedience is a holocaust in which the whole man without the slightest reserve is offered in the fire of charity to his Creator and Lord through the hands of His ministers. And since it is a complete surrender of himself by which a man dispossesses himself to be possessed and governed by Divine Providence through his superiors, it cannot be held that obedience consists merely in the execution, by carrying the command into effect and in the will’s acquiescence, but also in the judgment, which must approve the superior’s command, insofar, as has been said, as it can, through the energy of the will bring itself to this.’ (St. Ignatius, Letter on Obedience.)

This claim is presented as following the tradition of the Church on obedience. The innovation of St. Ignatius can however be seen by contrasting his position with that of St. Gregory the Great. In his Moralia, St. Gregory states that the merit of obedience lies in sacrificing one’s proud self-will.8 St. Thomas makes a similar point by describing the merit of obedience as consisting in sacrificing one’s proper will, i.e. one’s will as functioning independently of God.9 St. Ignatius however makes it clear that it is not self-will, but the entire human faculty of will itself, that is to be sacrificed; one’s self-will could not be described as ‘of great worth’. This is a sacrifice in the sense of an abandonment and a destruction, since it involves handing over one’s will to the will of another human being. Underlying this claim, of course, is the presumption of liberty of indifference, according to which one’s will necessarily functions independently of God. This presumption is something that St. Ignatius would have learned from his studies as a basic axiom. His conception of the sacrifice of the will was simply an application of this philosophical position to the religious life.

The character of the Society of Jesus was itself an important influence on the Jesuit understanding of obedience. Monastic obedience had always been strict, and examples of monastic obedience were plentifully used by writers to illustrate the virtue of obedience as the Jesuits conceived of it. But these illustrations ignored the fact that monastic communities were governed by detailed Rules – those of St. Basil, St. Augustine, or St. Benedict. The authority of a monastic superior was limited by the rule of the community, and had the purpose of bringing about the following of the rule. It was obedience to the rule, not to the superior as such, that was the fundamental tool of monastic perfection, and the object of monastic obedience. But the Society of Jesus had no rule. The decisions of the Jesuit superior were explicitly intended to take the place of the rule of life of the monastic community as the object of obedience and the path for spiritual perfection for the Jesuit. The primacy of law that was characteristic of monastic obedience was thus lost.

An obvious objection to the Jesuit conception of obedience was soon raised. It was remarked that acceptance of blind obedience would mean that heretical priests and bishops could easily lead their people into rejection of the faith. St. Robert Bellarmine’s response to this objection was that it was not a real possibility, because the preaching of heresy by bishops or priests would promptly be suppressed by the higher authority of the Holy See. This response of course required the pope himself to be incapable of heresy. The theory that the pope was not only infallible in his formal definitions of faith, but personally immune from heresy in virtue of his office, was accordingly first proposed in the Counter-Reformation, and argued for by Bellarmine. The theory was incompatible with the facts and the previous tradition of the Church – one pope, Honorius, had actually been condemned as a heretic by an ecumenical council – but it was required by the Jesuit conception of obedience, and soon came to be widely accepted. This conception of obedience was thus at the root of later ultramontane excesses, which appealed to the belief that the pope could not err in matters of faith – a superhuman privilege that was easily extended to the belief that the pope could not err in any way at all.

8

May

6

May

Having a Good Laugh…

Posted by Stuart ChessmanEamon Duffy, that is – at George Weigel’s expense:

“Ecstatic liberals hailed the return of the spirit of Vatican II, while agitated conservatives mounted damage limitation exercises. George Weigel, biographer and confidante of John Paul II, insisted that Evangelii Gaudium demonstrated a “seamless continuity” between the attitudes and emphases of John Paul II, Benedict XVI and Francis, a judgement which, if not tongue-in-cheek, appeared more than a little impercipient about the entire rhetorical impact of Evangelii Gaudium.”

http://archive.thetablet.co.uk/article/8th-march-2014/6/eamon-duffy

Meanwhile, Cardinal Kasper speaks at Fordham – including the following:

“Audience asks why feminist theologians are particularly suspect in the church today? Kasper esteems E. Schussler Fiorenza & Beth Johnson.”

Commonweal commentary: Obviously this was a response to news from Rome that the prefect of the CDF had criticized the LCWR for honoring Elizabeth Johnson, CSJ, whose book Quest for the Living God was taken to task by the USCCB Committee on Doctrine for “completely undermining the Gospel” (it really doesn’t).

“Kasper: Sometimes the CDF views things a bit narrowly. Aquinas was condemned by his bishop. So Johnson is in good company.”

https://www.commonwealmagazine.org/blog/kasper-kaveny-fordham

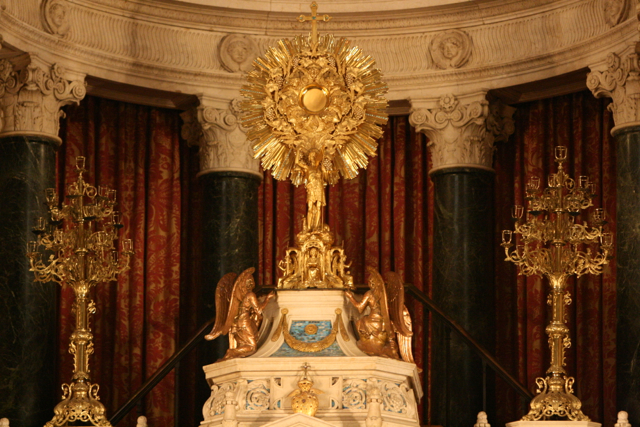

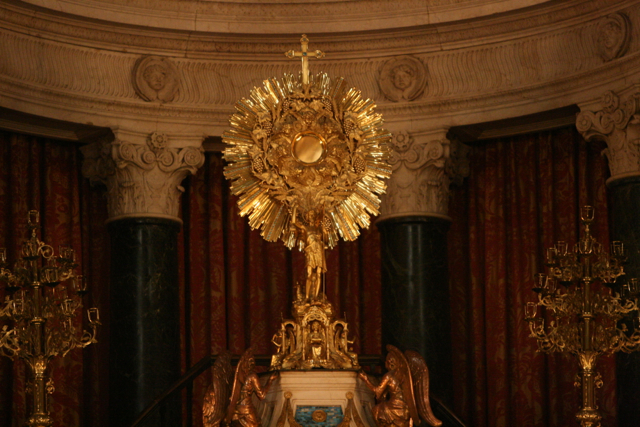

Church of Saint Jean Baptiste

184 East 76th Street and Lexington Avenue

“Ethnic parishes” are in bad repute with the Archdiocese nowadays. The creation in earlier times of separate churches for the Italians, the Slavic peoples, the Germans etc. is held responsible for the alleged surplus of Catholic churches in New York today. So the court historian of the Archdiocese, Fr. Shelley; so the publicists of the current Archdiocesan “realignment” initiative ”Making all Things New.” The party line is that since the “ethnics” have either vanished or have been assimilated we do not need their churches.

The truth is quite a bit more complicated than that. Since in the 19th century and well beyond the majority of the parishioners of the non-ethnic parishes of New York City were Irish, it could be maintained that all New York Catholic churches were “ethnic” from their origin. Yet even if we restrict the label “ethnic” only to parishes having a congregation employing a language other than English, the boundaries have been very fluid. Some churches have always been “ethnic” but with a succession of different nationalities, e.g. Our Lady of Sorrows (first German, then Italian, now ”Hispanic”). Other parishes have started out “non-ethnic” and have become “ethnic” (non-Hispanic): St. Raphael (now Croatian); Transfiguration (first Italian, then Chinese); All Saints (black – considered from the beginning “ethnic”). And, of course, in recent decades most Manhattan parishes other than the commuter churches and those located on the East Side north of 14th Street and south of 96th Street have become de facto “Hispanic” ethnic parishes. Yet others have started out ethnic and have become “generic” Catholic – e.g., St. Francis and St. John near Penn Station (originally German); St Elizabeth of Hungary (Slovak); Our Lady of Peace (Italian). Of this very last category the most spectacular example is the church of St Jean Baptiste on the Upper East Side (in earlier days, old Yorkville) 1)

St. Jean Baptiste parish was born in 1882 to serve the needs of the French Canadians. They had been present in New York from the early days of Catholicism. But in contrast to their prominence in the New England mill towns, French Canadians remained one of the smaller Catholic minorities in New York City. From its very beginning their parish accommodated other nationalities. An early focus of veneration was, just as in Quebec, St. Ann. A relic on the way to St Anne de Beaupre was venerated by a great multitude in the very first year of this parish’s existence even before its first church was finished; later in the 1880’s the parish acquired its own relic of St. Ann and the devotions continued and grew (if in competition with devotions at St Ann’s parish downtown). St. Jean remained a parish of the French Canadians until 1957. 2)

Now two circumstances radically transformed the life of the parish and created one of the most grandiose churches in New York City. First, in 1900, after early years under various pastors, the parish was placed in the care of the Congregation of the Blessed Sacrament, a religious congregation coming from Montreal. St. Peter Julian Eymard founded the Blessed Sacrament Fathers in Paris in 1856 –their first residence was in the strangely named Rue d’Enfer. (The name of the street is actually thought to have nothing to do with the underworld). Eymard labored to promote Eucharistic worship. That included preparing children for first Holy Communion, reaching out to non-practicing Catholics through the Eucharist and encouraging both Eucharistic adoration and frequent Holy Communion. 2) Of the community of Blessed Sacrament Fathers newly established at St Jean’s, Father Arthur Letellier was a particularly outstanding personality: a man of great devotion and an inspiring and visionary leader. He became pastor in 1903.

Second, the parish attracted the attention of Thomas Fortune Ryan, (1851-1928) an investor in many businesses who was reckoned the 10th wealthiest man in the United States when he died. He and his wife Ida Barry Ryan were major benefactors of the Catholic Church allover the country but especially in the South. 4) He had already established close contact with the Blessed Sacrament Fathers both at his country estate and in the city. He would attend the services at the small and new parish of St Jean Baptiste – although his residence at the time appears to have been – appropriately enough – in the parish of St. Ann. One day after having had to stand in an overcrowded service, Ryan asked Father Letellier how much it would cost to build a new church. “At least $300,000” said Letellier (a monstrous sum for the time). Ryan replied: “Very well – have your plans made and I will pay for the church.” The new St. Jean’s was born. 5)