This Thursday, May 9, is the Feast of the Ascension, a holy day of obligation. The following churches will offer the Traditional Mass.

Connecticut

St. Mary Church, Norwalk, 8 am, 12:10 pm, 7 pm

Sts. Cyril and Methodius Oratory, Bridgeport, low Mass7:45 am; high Mass 6 pm

Sacred Heart Oratory, Georgetown, Missa Cantata, 6 pm

St. Patrick Oratory, Waterbury, low Mass 8 am; high Mass 6 pm

New York

Holy Innocents Church, New York, NY, low Mass 8 am; high Mass 6 pm

Our Lady of Mount Carmel Shrine, 448 East 116th Street, New York, 7:00 AM Low Mass; 7:45 AM Low Mass; Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament exposed from 9:30 AM to 10:30 AM; 3:00 PM Holy Rosary and Divine Mercy Chaplet; 6:00 PM Confessions; 7:00 PM High Mass of Thanksgiving, 37th Anniversary of Ordination of Father Marian Wierzchowski SAC Pastor

Our Lady of Refuge, Bronx, Missa Cantata 7pm

St. Josaphat Church, Bayside, Queens, 7 pm

St. Paul the Apostle, Yonkers, NY, noon

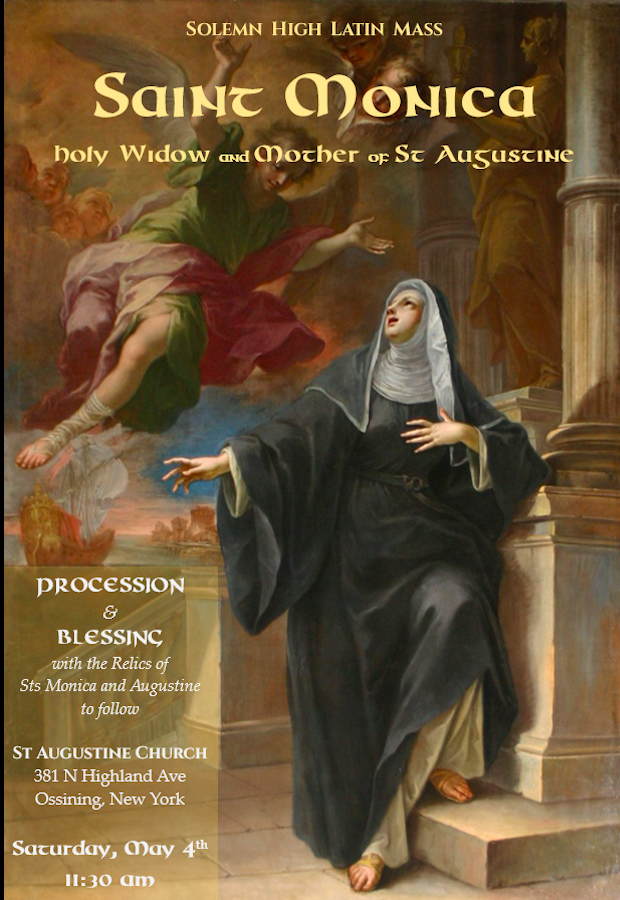

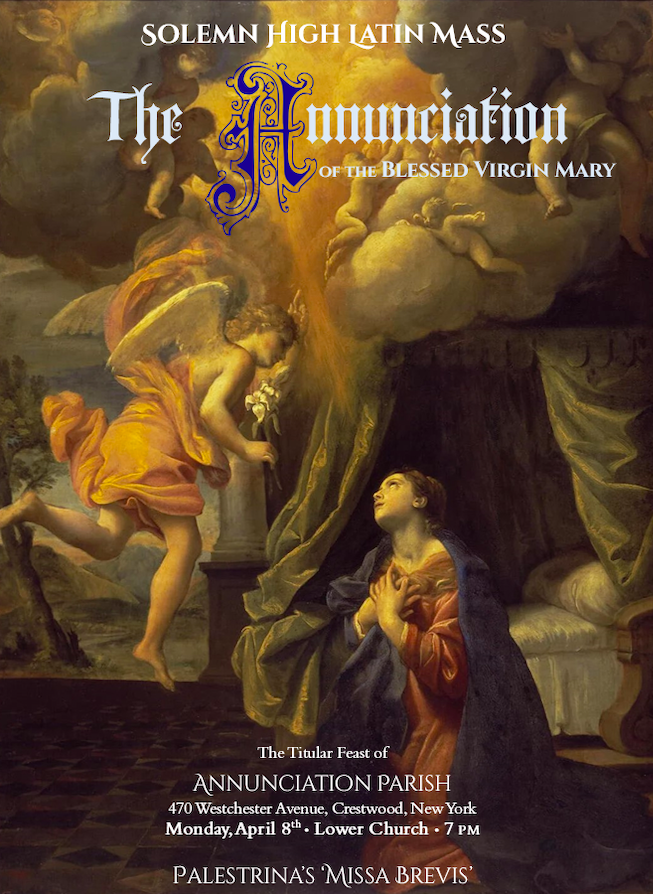

Annunciation Church, Crestwood, NY, 7 pm

Immaculate Conception, Sleepy Hollow, low Mass 7 pm

St. Matthew, Dix Hills, Long Island, 10:30 AM

St. Rocco, Glen Cove, Long Island, Missa Cantata 7 pm

Sacred Heart, Esopus, 11:30 AM

St. Mary and St. Andrew, Ellenville, NY, 7 PM

Church of the Holy Trinity, Poughkeepsie, 7 pm

New Jersey

Our Lady of Sorrows, Jersey City, 7 pm

Our Lady of Fatima Chapel, Pequannock, 7 am, 9 am, 12 noon, 7 pm

St. Anthony of Padua Oratory, West Orange, low Mass 9 am; high Mass 7 pm

Corpus Christi, South River, Missa Cantata, 7 pm

Shrine Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament, Raritan, 7 pm

St. John the Baptist, Allentown, 7 pm